The crux of the City Hall debate appears to be what makes sense economically: tear down or rebuild? And appearance: Can we sustain the function of this building and upgrade its tattered look? That’s what the Eugene City Council will be considering when it meets for a work session and regular meeting Sept. 22 and additional work session Sept. 24.

Does our City Council know:

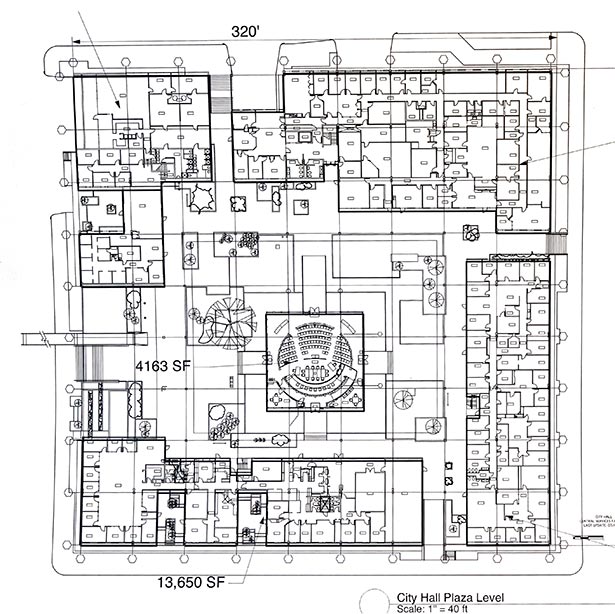

City Hall is still a young building, designed and built to last far longer than 50 years, and with seismic reinforcing it could easily stand another 50 to 100 years, and it can even be built higher. Mayor Edward E. Cone, in dedicating the building in 1964, declared: “The north wing has been projected and planned for six more floors when the city reaches the size that will be necessary for further expansion.” Eugene’s population at the time was about 50,000.

City Hall’s design is exceptional, even by today’s standards. The research, expertise and teamwork that went into designing the national award-winning City Hall are “brilliant,” architect and engineer Ray Wiley says. The Eugene firm of Stafford, Morin & Longwood was chosen by jury from 25 applicants. “The entire team contributed to the design from the very first meeting,” architect Jonathan Stafford says. The design team included a structural engineer, mechanical engineer, electrical engineer, landscape architect, a sculptor, a muralist and architects. None of the team members are alive today.

“It is an extraordinary design that would be difficult to improve upon,” architect George Hermach says. “The underground emergency shelter or vaults have significant value. The naturally illuminated public parking for 150 vehicles is ideal and worth millions.”

The structure is flexible. This particular type of design and construction involving a post-tensioned two-way waffle slab platform allows for flexible construction or reconstruction on the second floor, says Jayme Vasconcellos who supports the architects. Just about anything can be built on this concrete platform. “All of the concrete block walls can be removed and replaced with stud and insulated walls or the block walls reinforced, furred and insulated,” says architect Otto Poticha.

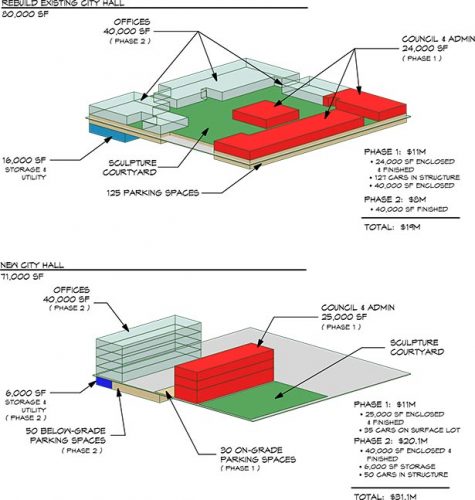

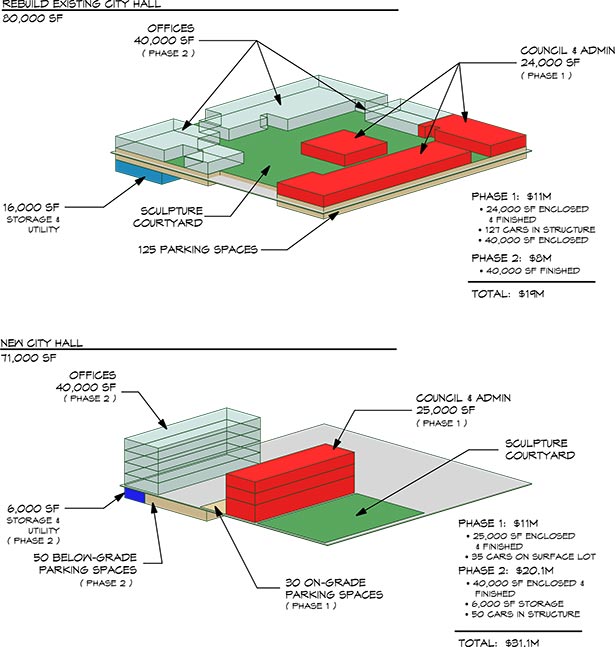

The Turner Construction estimate of $23 million for renovating the entire 64,000 square foot upper level compares with Rowell Brokaw Architects’ estimate of $40 million for all new construction — $15 million for demolishing and building a new Phase I City Hall plus about $25 million for Phase II city offices, creating about 65,000 square feet. “We just do not understand why the city should spend $40 million to get what they could get for $23 million,” architect Ward Beck says. Other architects have come up with different, but similar numbers, based on their analyses.

The Turner study is still valid. The city manager says the two-year-old analysis of City Hall options is out-of-date and irrelevant. But architect Ward Beck says, “We reconfirmed with Turner that their numbers are still accurate and include a 4.5 percent inflation factor for a two-year delay in start of construction.”

The earlier renovation decision was good. Back in 2012 the council supported “rebuilding the existing structure,” Poticha says. Why the change? “I have been told that the justification for this change is that a new building and a rebuilt building will be the same cost,” he says. “This is hearsay and no documentation to support that claim has been available.”

The city can save millions by doing just the $15 million Phase I renovation now, which would provide roughly the same space as a new City Hall, but would include large shelled spaces for future offices and expansion as future funds become available. Meanwhile, the building would still have its 125 or so covered parking spaces. (An accurate number of parking spaces is unknown since some spaces were designated for oversized vehicles.) However the numbers are crunched, “Rehab will cost less than new construction,” architect Dennis Casady says.

A renovated City Hall can be at least as energy efficient as a new City Hall. All of the energy-efficiency features of a new City Hall can be included in a renovation, except for some passive solar design. But the much larger, unshaded roof on the existing structure could accommodate enough south-facing photovoltaic panels to power all of City Hall and have excess electricity to sell to EWEB. A rebuilt City Hall could become net-zero-plus for energy, according to Wiley.

Grinding up City Hall would be toxic. Mechanical demolition of concrete structures involves dust, noise and vibration from heavy equipment and can even cause damage to nearby buildings, according to the Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice. Downtown urban areas are of particular concern, and “unforeseen circumstances may arise.” See wkly.ws/1tb. Concrete dust is difficult to contain and considered hazardous, particularly since it often includes heavy metals and limestone. Trees will not grow in unprocessed concrete rubble.

“How can we justify tearing down and grinding up our buildings every 50 years,” architect Bill Seider asks, “only to build new buildings with newly resourced and manufactured materials to take their place on top of the compacted rubble of the past.”

City Hall has a huge existing utility room. The basement room of 16,000 square feet for mechanical and electrical services and storage can be used for new utilities and/or repurposed, according to Vasconcellos. Tearing that up would be a big waste, he says.

City Hall is not prone to “collapse.” Architects say a distinction needs to be made in seismic vulnerability. A new City Hall and a reinforced old City Hall can both be severely damaged in a major earthquake, but both will stand well enough to avoid loss of life. By contrast, police and fire department buildings are designed to higher seismic standards and will hopefully not only survive major quakes, but remain fully functional. A seismic retrofit of City Hall would cost about $850,000 while demolition could cost $1 million or more, Poticha says.

An elevated City Hall is not a bad idea. The renovated new police department on Country Club Road is similarly elevated. Dams on the Willamette and McKenzie rivers provide some flood control, but Eugene’s downtown is still vulnerable if exceptionally heavy rains cause Amazon Creek to overflow. The parking under City Hall could be flooded, but elevated city offices would stay dry.

Eugene is notorious when it comes to historic landmarks. “No other city in Oregon has as fine a record as Eugene in destroying its architectural history,” says architect Eric Hall. City Hall is worthy of national historic designation as a prime example of mid-20th century Pacific Northwest architecture, says Poticha. “I would consider it a crime to destroy such a national treasure,” says Wiley.

Delay the demolition, Seider says, and “really practice a carbon-neutral philosophy for a sustainable community we all can be proud of.” Casady agrees, saying “Today’s hot topic is sustainability. Tearing down is not sustainability.”

City Manager Jon Ruiz declined to comment on the challenges to his proposals from members of the Save City Hall group of architects and engineers, saying these issues would be discussed in the upcoming City Council work session.