By Ryan Nguyen and Henry Houston

What if nuclear power was the answer all along to clean energy?

Oregon voters implemented a moratorium on nuclear power plants nearly 40 years ago, but state Sen. Brian Boquist of Dallas wants to exempt small nuclear reactors from the prohibition, allowing companies such as Portland-based NuScale to sell its small modular reactors (SMRs) in the state.

One expert calls Boquist’s bill an amateur effort for SMRs, and during the Legislature’s 2017 testimonies, critics said Boquist is trying to create a loophole around the will of Oregon voters.

Despite the bill’s language, NuScale says its SMRs are a resilient, affordable and clean energy source.

Before Boquist made news for going rogue and demanding Oregon State Police send armed bachelors to come and get him, he spoke with Eugene Weekly about Senate Bill 444, a bill he knew was destined to go nowhere. He says he doesn’t think the bill will ever pass during his time in the Legislature, but he wants to keep putting the idea out there.

SB 444 would exempt SMRs from state restrictions prohibiting nuclear power plants in Oregon. If a city or county government wanted an SMR in its jurisdiction, voters would have to approve it, the legislation says.

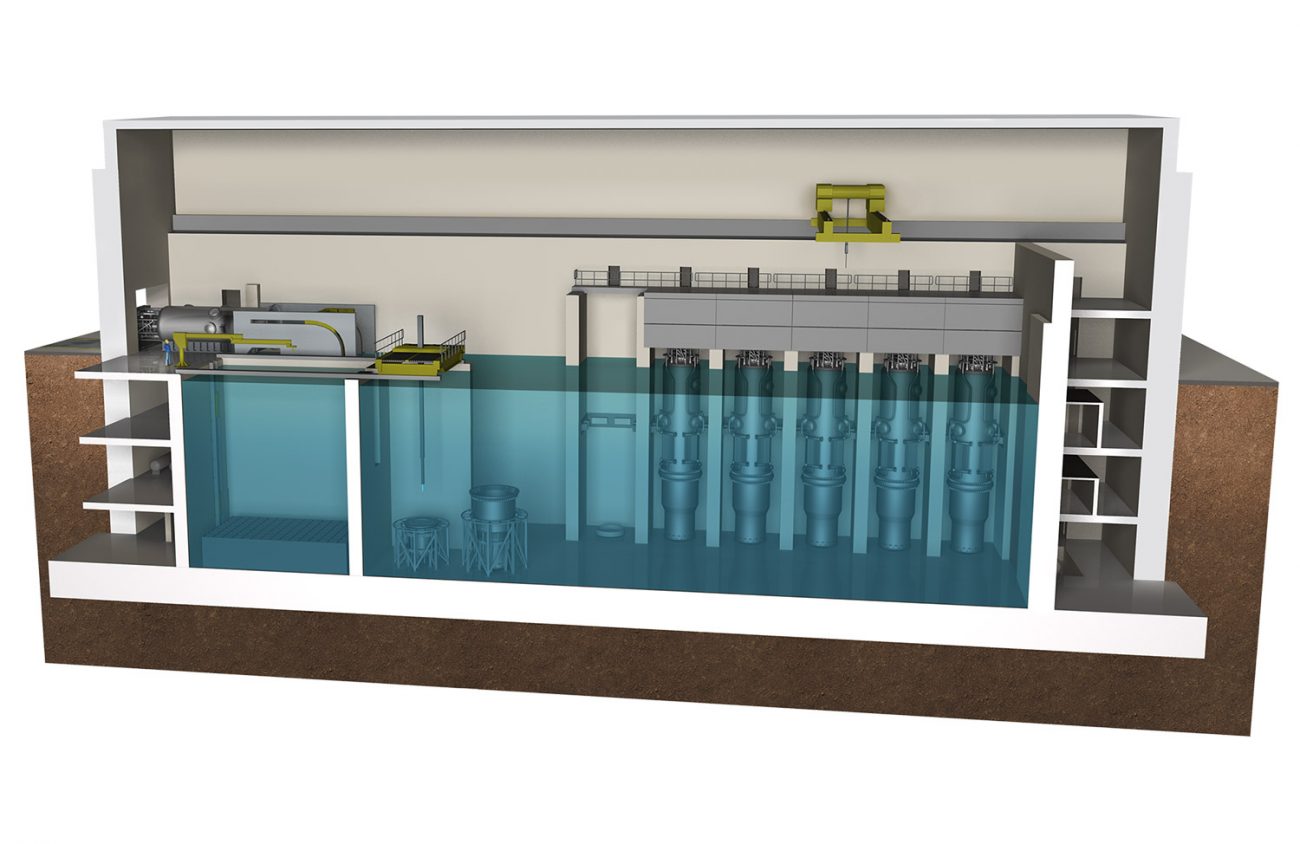

Although Boquist calls it legislation to allow a “nuke in a box,” an SMR is actually a scalable nuclear power plant, so a power company can develop a nuclear power plant according to its energy needs by adding modules when energy consumption increases. NuScale’s models, for example, can offer power generation from 60 megawatts up to 720MW of gross energy output. At its higher end, that’s enough for a city with a population of 683,000 says Chris Colbert, chief strategy officer at NuScale.

NuScale’s technology originally began in 2000 in collaboration with Oregon State University, Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory and Nexant.

In 2017, the Legislature had open testimonies about nuclear power plants addressed in SB 990 (same bill, different name).

Chuck Johnson, a director of the Task Force on Nuclear Power for Oregon and Washington Physicians for Social Responsibility, told legislators that ever since Oregon voters imposed a moratorium on nuclear power plants, no one has found a safe, permanent repository for high-level nuclear waste.

Other testimony, including from Multnomah County Democrats and Eugene PeaceWorks, questioned the legislation’s language that creates a loophole for nuclear power plants that sidesteps a state election to override the nuclear power plant moratorium.

EW sent a copy of Boquist’s SB 444 to Michael Golay, a professor of nuclear science and engineering at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After reading the bill, it struck him as an “amateur effort to do something nice” for SMRs, he says. Golay says he found “almost everything to be confusing.”

Golay adds that what’s concerning is having a county decide on whether to host a nuclear power site.

“This isn’t really the kind of question democracies are well organized to answer,” he says.

Colbert says NuScale isn’t afraid to conduct outreach with the public about the positives of nuclear power. When NuScale was pursuing a project with Utah Associated Municipal Systems, the company held more than 110 public meetings, some lasting 30 minutes and others up to two hours. After these meetings, people in that area began to change their views on nuclear energy. This project, which will provide power for customers in Utah, California, Nevada, New Mexico and Wyoming, will be NuScale’s first-ever SMR in the U.S.

When talking with people who are against nuclear energy sources, he says presenting SMRs as a means to decarbonize and assist renewable energy helps. And, although nuclear power does create waste, Colbert says the amount of regulations in effect to track nuclear waste ensures it’s being tracked, unlike coal, for example, which emits a lot of its waste through air pollution.

He adds that NuScale’s SMRs are also resilient and can weather through natural disasters.

“They’re really designed for the worst-case scenarios,” he says.

If Boquist’s legislation one day saw the light of a governor’s signature, a perk of using NuScale’s SMRs is that they might attract an out-of-state investor that wants to bring its business to a carbon-free energy generating state, Colbert says.

“It’s good to be able to support an Oregon company by believing in its products and using them,” he adds. “One of the key attractions for Oregon is that they can claim they have a high percentage of carbon-free generation.”

Colbert says that NuScale has a system to contain its nuclear waste.

However, when nuclear waste goes wrong, it could look a lot like Hanford, Washington, which produced weapons-grade plutonium during the Cold War and also stores commercial nuclear waste. A 2019 report from the Department of Energy estimates that it could cost from $323.2 billion to $677 billion to clean up nuclear waste at the site.