This month President Donald Trump broke records — his own records — for tweeting. He tweeted and re-tweeted more than a hundred times in one day. As of last month, according to The New York Times, he has sent 11,000 tweets.

When he ran for president, the question was raised whether he could ever be presidential. He said he would be one of the “most presidential” presidents.

This phrase would make a fine quote to be stitched on a piece of embroidery for the Tiny Pricks Project — I’m guessing someone likely has.

The Tiny Pricks Project was founded and is curated by textile artist and activist Diana Weymar, and it claims to be “the material record of Trump’s presidency” with more than 2,600 pieces of embroidery in the project.

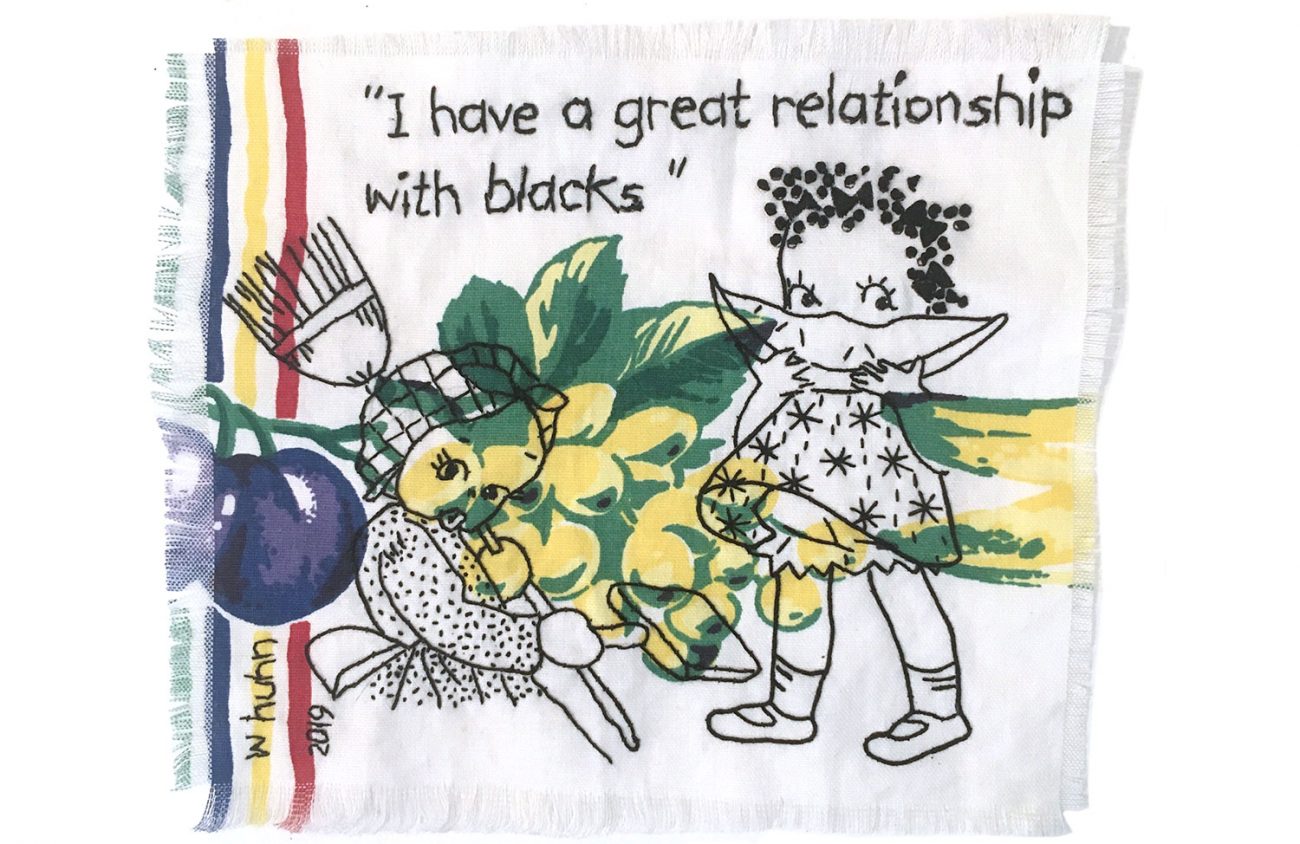

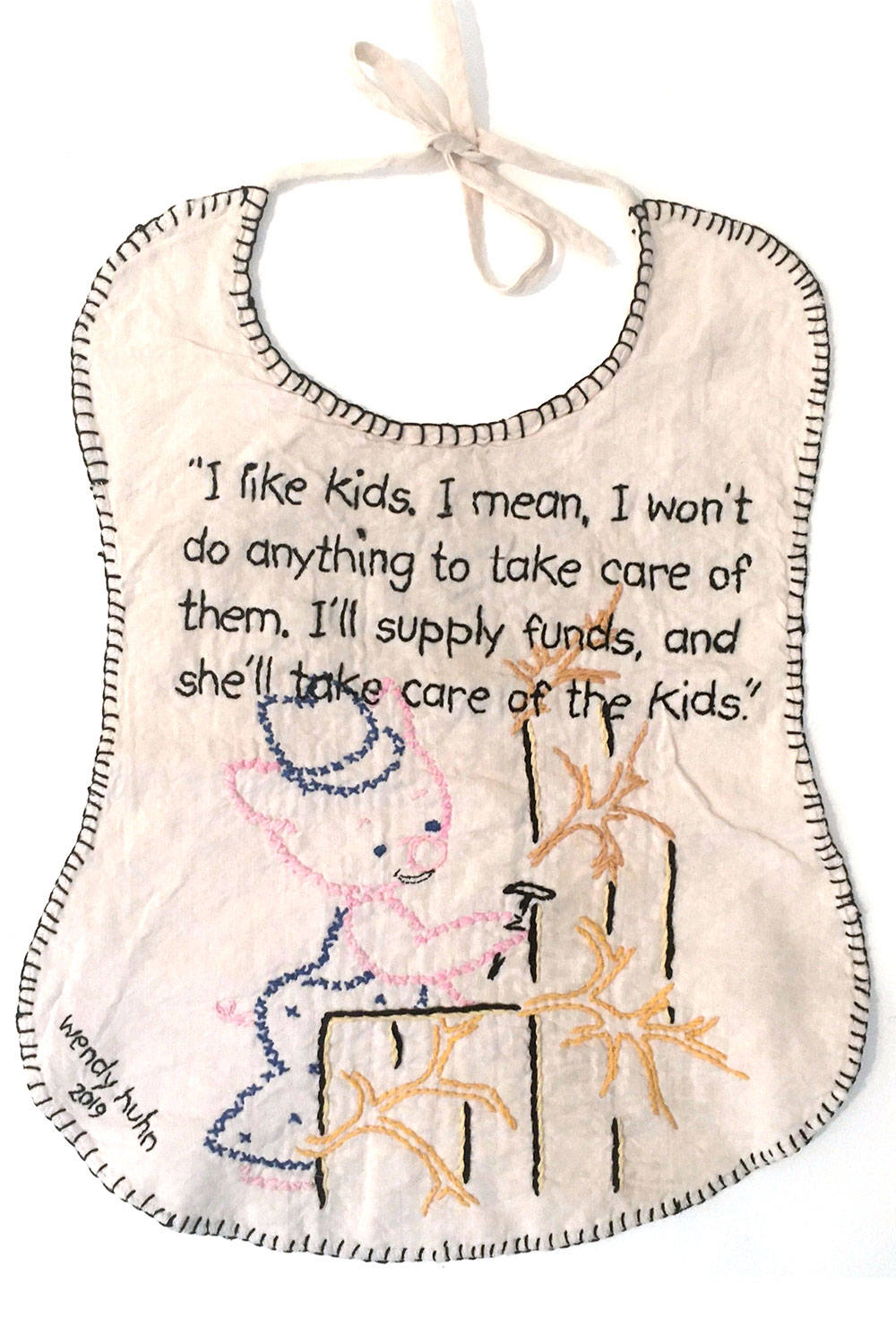

It works like this: Pick a quote by the 45th president, stitch it as vintage embroidery and submit it.

You don’t have to be an artist to participate, although Eugene artist Wendy Huhn certainly is one. She graduated from the University of Oregon in 1980 with a degree in textile art. When I first contacted her by email I asked, “What is your connection to the project?”

She shot back, “My friend sent me the site. And I hate Trump.”

Her friend — actually several friends — told her about the project after they read an article on it in The New Yorker titled “Stitch ‘n’ Bitch for the Trump Era.”

Huhn was already attempting to draw attention to her views about Trump with a bumper sticker that read, “STD: Stop the Disease, Stop the Donald.”

The Tiny Pricks Project offered a way to speak her views on “The Donald” through her art. The STD part of the sticker “draws people in,” she says. Then she likes to watch how they react getting closer to the rear of her car. It’s the same with stitching the president’s words. The nostalgic fabrics of bygone eras draw people in — then they read the president’s words.

You don’t see that many anti-Trump stickers, she tells me, because people are afraid their cars will be vandalized.

“Are you afraid?” I ask.

“No,” she answers. “It’s good to get the word out.”

As has been noted since practically the beginning of his term, the president’s barrage of tweets, no matter how shocking they might be, are forgotten when replaced by the following day’s output. The Tiny Pricks Project creates a written record using thread and cloth.

Weymar hopes the collection she accumulates will ultimately find a permanent home in a museum. For now she has parts of it on exhibit in galleries. Lingua Franca, a shop in Manhattan, exhibited a portion this summer and early fall. They referred to the show as a global “public art project.”

Weymar is still taking submissions, and no work is turned down. How long will people be invited to participate? Until “he is out of office,” she says.

Her primary source for quotes is Trump’s twitter feed, but she also has stitched words from his years of celebrity beforehand.

Huhn’s favorite source is a podcast called “What the F—k Just Happened Today?” Listening to this roughly five-minute recap of the day’s news, or reading it in written bullet statement format, Huhn doesn’t have to listen to hours of news anymore.

Her textile art approach is a perfect match for the project. She has been collecting vintage cloth for years. Using a thread and needle, she says, people often assume you’re trying to make a statement about gender — which, she says, she is not. She knows men who embroider, too.

But there is something strange, powerful and beautiful about seeing the president’s often sexist or racist words stitched on cloth. Out of the twitterverse context, we see his language in the hands of participants who oppose it.

Huhn, by the way, is not a fan of knitting or crocheting. Those approaches are “too mechanical” for her. She likes playing with vintage cloth and images from the past. She especially appreciates ones that seem sweet and endearing: an image of a child or an animal embroidered on an antique handkerchief.

They draw people in.

Huhn’s pieces relate to Trump’s sayings about women or minorities. One work shows an image of a little girl from another era, seeming shy or surprised by the quote stitched beside her: “When you’re a star they let you do it, they let you do anything, grab them by the pussy.”

So much has been said since these words, spoken to Billy Bush in 2015, hit the public sphere. Seeing them again reminds me they are the very words that inspired the mass protests that occurred across the globe after Trump was elected.

Protesters took to knitting or crocheting “pussy hats” to make their statement.

In today’s climate, where many are disillusioned, disheartened or plain shell-shocked by the barrage of tweets, the Tiny Prick Project carries on in the tradition of the pink hats.

The embroidered pieces — the tiny pricks — may not be as visible as the marches were. They have not stopped traffic in the streets. But the project has taken on a life of its own. Besides the thousands of submissions and coverage from The New Yorker, it has garnered attention from fashion and art magazines such as Women’s Wear Daily, Vogue and Artnet.

Huhn, who lives in Dexter, has never met Weymar. The directions for participation are on the project website and she sent her pieces in. She hopes to meet Weymar at the opening for the collection’s future, permanent home — wherever that might be.

More work from the Tiny Pricks Project can be seen at TinyPricksProject.com.