People are still wearing masks, but it’s good to see art in person again. My first in-person museum viewing in 15 months, since museums were closed due to the pandemic, was to see Dale Chihuly: Cylinders, Macchia, and Venetians from the George R. Stroemple Collection.

Coming out of the exhibit, which is up until Aug. 28, I’ve learned some things about the genre of glass art, like that a revolution took place during the ’60s and ’70s which was started in part by Seattle-based glass art maestro Dale Chihuly. The exhibit shows how he moved away from the functional cylindrical vessel towards the vibrantly colored monumental pieces that characterize his work today.

The first time I saw Chihuly’s work was at a casino on the Las Vegas strip. His glass installation hangs from the lobby ceiling of the Bellagio Hotel. It is eye-catching, to say the least. Even within the over-the-top décor of the Bellagio — a casino hotel made to resemble the Italian town of Bellagio — Chihuly’s installation “Fiori di Como” stands out.

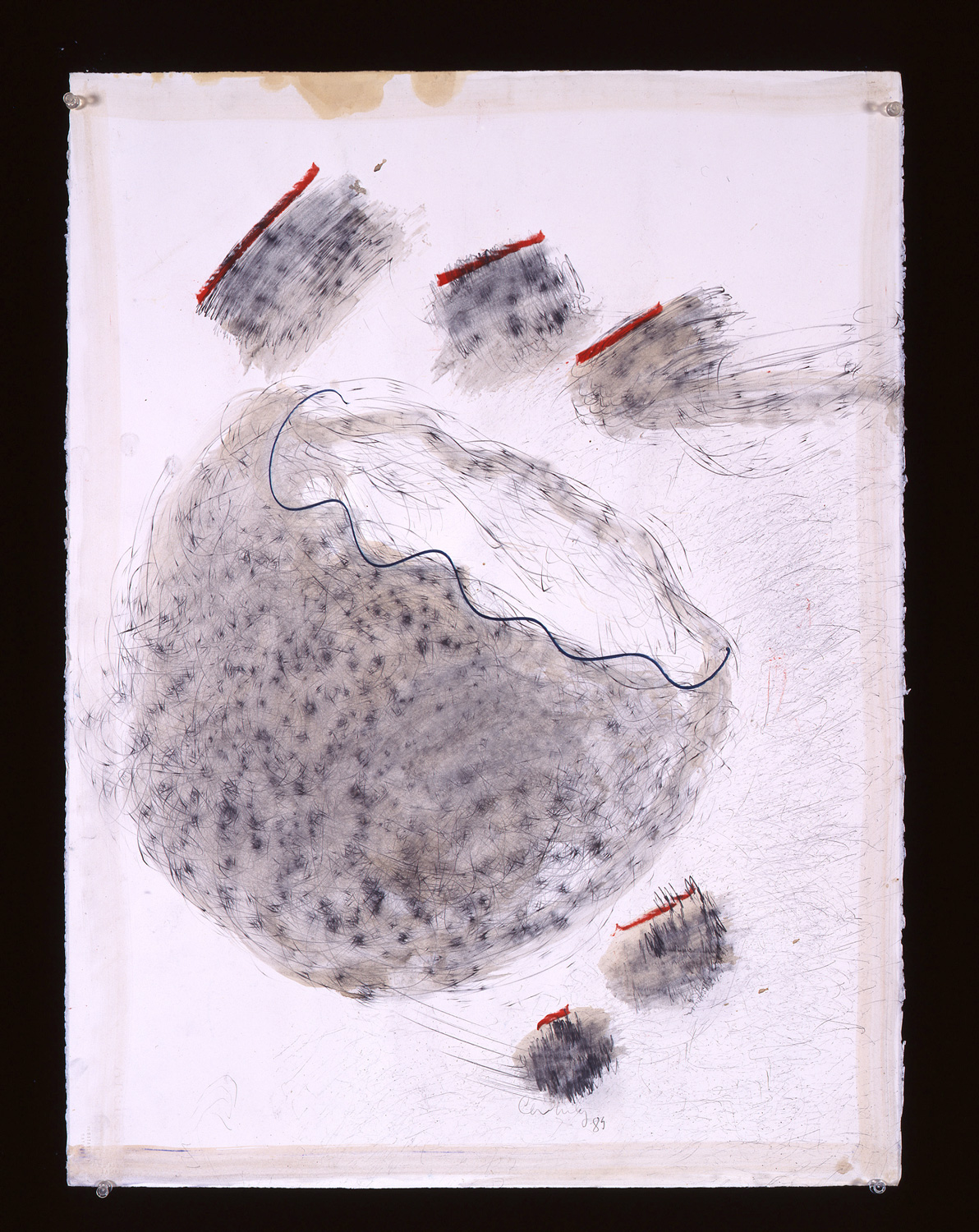

Nothing so large is on display or hangs from the ceiling at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Salem. But we get to see drawings by Chihuly that offer a look at how he visualizes in 2D. And the three styles or series correspond to his evolution from a student of glass art to a master or “maestro.”

Some artists, once they find a style, stick to it, says exhibit curator and museum director John Olbrantz. But Chihuly “is never happy with the status quo.”

Olbrantz should know. He curated Chihuly’s first retrospective in the ’80s, when he was director of a different museum in Washington. The artist was market-savvy even back then. Olbrantz says Chihuly is a master of marketing as well as a maestro of glass art.

“There’s nothing wrong with that,” he adds.

Enlarge

Courtesy Photograph

I agree, acknowledging the unspoken double standard for artists. Creative people need to make a living, same as everyone else, but those who are highly successful are often suspected of not being true artists.

More than 72 glass artworks are on display in this show. A simple statement by the artist explains the origin of all of it.

Referencing blowing a bubble when he was a boy, he says, “Since that moment I have spent my life an explorer searching for new ways to use glass and glassblowing to make forms and colors and installations that no one has ever created before — that is what I love to do.”

The first pieces in the exhibit, done when Chihuly was a student, are symmetrical cylindrical vessels. They resemble functional vases. The Maachia period next on display looks more like the art installation I saw at the Bellagio — brilliantly colored and organically shaped vessels or sculptures.

The Macchia series began in 1981 when Chihuly woke up one day “wanting to use all 300 of the colors in the hot shop.” He started by creating a color chart with one color for the interior of the sculpture, another color for the exterior and yet another for the lip wrap, “along with various jimmies and dusts of pigment between the gathers of glass.”

Thanks to a glossary of terms on display, I can tell you that a lip wrap is a “trail, usually of a contrasting color, wrapped around the edge of the rim.” And that jimmies are small lengths of colored glass threads.

Also, a gaffer is a master glass artist in charge of a group or team of glassworkers.

Creating glass sculptures, Olbrantz says, doesn’t fit with the idea of the solitary artist working on their own. Each hot shop, or studio, has a maestro who leads the design, a gaffer and someone to blow in the pipe. Olbrantz likens the team to an orchestra. The maestro is the conductor and the other people in the shop are the orchestra. Without them there would be no music — no art. Still they all look to one person for direction.

The series titled “Venetians” is inspired by glass art that Chihuly saw in Venice, Italy, that was blown for the Venini glass factory. My favorite pieces among the Venetians are the Bottle Stoppers. The oversized glass stoppers are inspired by perfume bottles and decorated with mythic-like figurines made by Italian sculptor Pino Signoretto. These elaborate and strange pieces look like their namesake, except they are monumentally sized stoppers without bottles.

So in the end we are left with “just” the art.

Dale Chihuly: Cylinders, Macchia, and Venetians from the George R. Stroemple Collection runs through Aug. 28 at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art, 700 State Street, Salem, on the campus of Willamette University. Hours are noon to 5 pm Tuesday through Saturday; admission is $6 adult, $4 seniors, $3 students, free 17 and under.