Docked on the blue waters of the Florence waterfront is an improbable duo with enough stories to fill a medium-sized novel and enough years together to fill a lifetime.

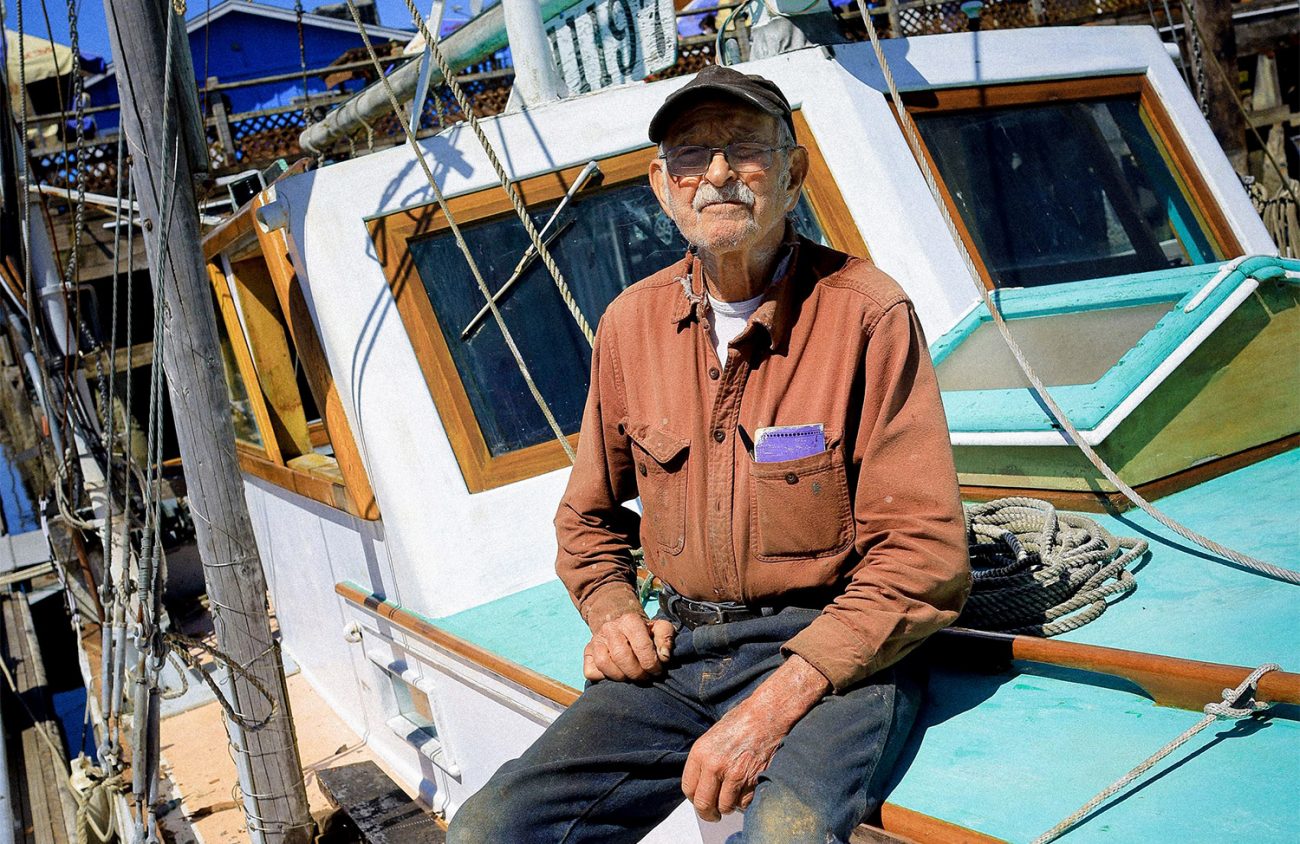

Retired commercial fisherman Walter Fossek, a high school dropout from Springfield, sits portside on his 52-foot boat with a glamorous past, known as the Otter. As people walk by, he says hello and chats with them about the happenings of the dock, where he spends his days maintaining the Otter bow to stern and reminiscing on a life full of crab pots and peach trees.

At 93, Fossek has the wizened, tan appearance of someone who has spent decades on the water. He wears a battered baseball cap to protect his bespectacled eyes from the sun, and his hair is pulled back in a thin gray ponytail.

The Otter is sleek and elegant, but scars in its wooden siding hint at a colorful youth.

“I grew up seeing the Otter on the docks, and it’s the only one that I can remember that’s still around from my days as a kid,” says Port of Siuslaw manager David Huntington. “And Walt’s always been here. If it wasn’t for that boat, at his age, I don’t know what he’d be doing. I think it keeps him going.”

Fossek was born on his family’s farm east of Springfield on Aug. 19, 1928. Growing up in the Great Depression, he was put to work at a young age, and recalls a youth spent irrigating three acres of peaches on the farm. He sometimes saw other kids playing as he worked, and says he would think to himself, “What a foolish bunch of guys.”

In 1944, when Fossek was 16, his family sold the farm and moved to Florence. Fossek initially continued attending high school after the move, but “lost interest” and dropped out during his sophomore year.

After leaving school, Fossek spent some time building boats for purchase, but when he sold his first boat, it only made one or two dollars more than what it cost him to build.

“That didn’t seem like a way to get rich,” Fossek chuckles.

Fossek decided to build himself a boat. He started out taking the 16-foot salmon troller on the river to play. Eventually, he took it to the ocean, which introduced him to commercial fishing.

But Fossek’s 16-footer, whose name he no longer remembers, and the 27-foot salmon troller Tradewinds that followed, were both too small for a successful fishing career. A long search for a new boat commenced, one that remained fruitless until 1953, when he stumbled upon a beaten-up yacht in need of a new mast.

Luxury and Danger

While some details of its origins are convoluted and often contradictory, it is clear that the Otter’s early life was nothing if not exciting. Designed in 1913 by Los Angeles yacht racer Matt Walsh and built for L.A. millionaire oilman and movie mogul Frank A. Garbutt, it started out as an excursion boat transporting passengers to Santa Cruz Island, off Santa Barbara, for weekend parties and summer vacations.

In 1913, Santa Barbara newspapers reported the Otter taking the entire cast and crew of the silent film production Calamity Anne’s Dream, directed by Lorimer Johnston and produced by Flying A Studios, to Santa Cruz Island for filming.

The Otter was also briefly used for hunting down pirates off the coast of California. On one occasion, the pirates attempted to hijack and steal the boat, but the captain had the forethought to disable the engine before they got aboard, according to news reports at the time.

During the Depression, the Otter presumably faced a few years of sad neglect before it was repurchased in 1935 by Walsh, its designer, for only $340. He later sold it to a world sailor who took it to Samoa.

Legends abound concerning the Otter. One has it that Western writer Zane Grey owned the boat for a time. Not true, Walsh’s daughter, Helen Walsh, told The Register-Guard in 1968, though she said he could have been a passenger on the Otter.

Legend also has it that after Walsh bought the boat back in 1935, he bet a friend $10,000 that he could fix up the downtrodden Otter enough to beat a certain speedier sailboat in a race. Helen Walsh didn’t dispute the legend that her father walked away from that bet $10,000 richer.

Limping into Oregon

In 1950, the boat belonged to a World War II pilot who wanted to sail it around the world. A short time into his trip, the pilot and two of his friends hit stormy weather off the coast of Coos Bay. They abandoned the boat and left it to its own devices, and Fossek says it was beaten “halfway to pieces” by the storm.

Fossek and his brother Ernest frequently visited a marine supply store in Coos Bay for boat parts, which is where the Otter had ended up after its near-death experience on the coast, and where it at last crossed paths with its most loyal owner.

Though some at the shop dismissed it as a “wreck,” Fossek could see that most of the repairs the Otter needed were purely cosmetic. And because, in addition to its sails, the Otter was motorized, converting it into a fishing boat was completely doable.

The trouble was the timeline. Walt and Ernest Fossek took the Otter to another shipyard to do their repairs, where they were told it would take two men a month to get the boat floating. And the owner of the shipyard did not have that kind of time.

“This big shipyard had a lot of boats waiting,” Fossek says. “The owner kept hounding us — he was a hard driver in those days. He was going to put us in and let us sink if we didn’t get it done.”

In the end, Fossek and his brother fixed the Otter in a week, replacing its two broken masts with a single tall Douglas-fir pole and converting it into a fishing boat.

The Rescue

One fall day in about 1966, Ernest Fossek and his girlfriend were travelling down to Florence from Newport in his boat, the Dixie Lee. Their boat was struck by a mountainous wave, which knocked it end over end until it landed on its side in the water. The force broke out a window, cutting into the muscle of Ernest’s arm, and the cabin filled with cold water.

When the two didn’t show up in Florence, Fossek and his father traveled up the coast to find out what had happened. They stopped in Yachats to get a view of the ocean. From there, they saw the bow of the Dixie Lee sticking out of the water.

Walt says he hurried back to Florence “like a maniac” to get the Otter started, unsure of whether his brother was dead or alive. He and the Otter, accompanied by a friend, fought rough waves to get back to the Dixie Lee, but when he reached his brother’s boat, he saw no sign of life.

After a moment, he spotted what looked like a couple of birds in the water. He steered the Otter toward them, and as he pulled closer, saw Ernest’s arm shoot into the air.

Once Fossek had pulled Ernest and his girlfriend out of the water and the Otter had gotten them successfully back over the bar, they were met by ambulance attendants and the fire department in a skiff.

“They pulled up alongside and gave my brother and his girlfriend oxygen, which they really didn’t need,” Fossek says. “They were more interested in a cigarette.”

A Hobby and a Lifestyle

During tuna and salmon fishing season, Fossek worked out of Florence. He primarily fished alone, though he recalls a girlfriend who insisted on going with him and the Otter on fishing trips.

The relationship didn’t last, and Fossek never married. But he had a more regular team operation going with his brother, whom he worked with intermittently from the 1960s through the 1980s, when Ernest retired. In the winter they crabbed together, originally in Winchester Bay and then in Eureka, California, where the buyers paid them better. Fossek says that at one point they had about 200 operating crab pots there.

Ernest died in 1993, shortly after his retirement, and Walt Fossek inherited the family property in Florence, where he remains close to the Otter.

Though he retired from fishing in the late 1980s, Fossek has spent the last 30 years maintaining his beloved boat. He varnishes and paints it continually, and gives it a bath every spring. Every other year, he rotates the boat so he can paint the bottom and remove any barnacles and algae that might affect its handling.

“It’s just about a full-time job,” Fossek says. “Washing a car is a bit of a project, and this is 50 times as much.”

Huntington says the amount of time Fossek has put into the Otter’s survival is “unbelievable.”

“I’ve never seen anyone work on a boat as much as he does, especially at his age,” Huntington says. “He cares about that boat, you can tell.”

While their days of hauling crab pots and saving family members from certain death are over, Fossek and the Otter can’t seem to part ways. Fossek admits that it would be financially sensible to sell the boat, and less work for him. But in a relationship as uncanny as this one, emotion rarely yields to logic. So when I ask him why he doesn’t sell the Otter, he just laughs.

“Why don’t I? It’s part of my hobby and of my lifestyle,” he says. “I’m emotionally attached to the boat, because of all the good and bad times we had together.”