On any given day the Washington Jefferson Skatepark is filled with noise. It’s noise that may sound random or chaotic for the uninitiated, but a well-tuned ear may be able to suss out the symphony in the commotion.

The skidding is a skater who’s pulling off an old school trick from when the sport was nascent in the ’70s. The cracking is skateboarders pounding their decks — the wooden part of the skateboard — against the ground in applause for someone pulling off an impressive trick. The slapping is shoes on concrete as a new skateboarder learns to “push” to move around the skatepark. And the grinding is a skateboarder’s trucks (the metal part connecting the deck to the wheels) riding on a metal rail.

“It’s a church for us,” says 48-year old Mike Crespino, who’s planning to skate down to San Francisco from Eugene to raise awareness for mental health. “We all go to church. We all say our hellos and nods and we answer back with hoots and hollers and board smacks.”

Since its construction in 2014, many skateboarders at the Washington Jefferson Skatepark and Urban Plaza have found a tight knit community. But in the past two years, that community has suffered the loss of two beloved skaters to mental health-related deaths.

In 2021, Silas Strimple, 18, was found dead on a conveyor belt at an Austin, Texas, recycling center. Strimple, according to his mom, Dena Drake, had paranoid schizophrenia.

Then on March 11, 2022, South Eugene High School student Ben Moody, 17, died by suicide.

In 2020, which is the most up-to-date data from the CDC, 10 children and adults ages 15 to 24 died by suicide in Lane County. Although Lane County Public Public Health officials don’t have specific numbers, spokesperson Devon Ashbridge says in 2021 death from suicides by people under 24 was higher than 2020. And she says the first quarter of 2022 suggests this year could be trending similarly to 2021’s rate.

The deaths of Silas Strimple and Ben Moody show there’s a lack of mental health resources for youth, some of their friends and loved ones say. And mental health awareness is what’s driving Crespino to skateboard down to San Francisco.

Local skateboarders want to have a memorial to Silas and Ben at Washington Jefferson Park. But first they need to fundraise. They’re raising money for it — an estimated cost of $20,000 — through selling skateboard decks honoring the two skaters. When they have the money, they’ll need to decide what the memorial will be and work to get the city of Eugene on board with the installation.

Crespino hopes to reach more donors, as well as to raise awareness about mental health, when he skateboards to San Francisco to deliver a memorial skateboard to Drake Moody, Ben’s older brother.

Enlarge

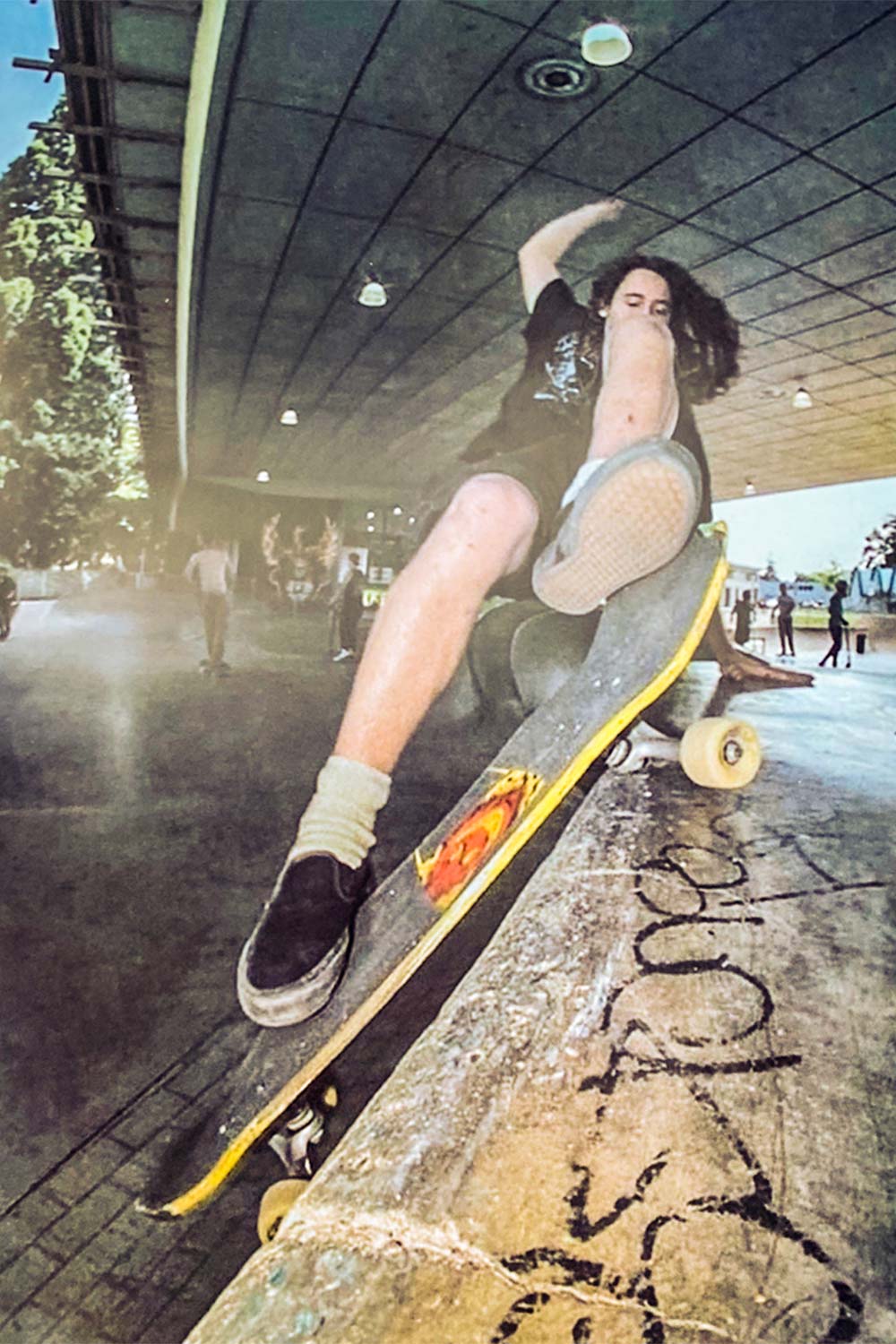

Watching Ben or Silas at the skatepark “was skateboarding poetry,” Crespino says. “They had the ‘thing.’ They ripped, and everybody knew it.”

Enlarge

Dogtown and Strimple

Crespino remembers seeing Silas Strimple as a child 10 years ago, skateboarding around WJ Skatepark wearing a death metal T-shirt. As an older skateboarder, Crespino says that seeing children at the park, he always hopes that they “get it” and decide to join the community.

And seeing Strimple wearing the death metal shirt, Crespino saw an opportunity to do his part in pulling the kid into the skateboarding world. “As he zipped past me at the park, I said to him, ‘Give me that shirt,’” Crespino says. He remembers young Silas skating by with an awkward laugh, like Beavis’s signature staccato chuckle from Beavis and Butthead. “But he smiled big, and I thought, there’s my in with this one.”

Strimple’s 2021 death made headlines when his body was found at an Austin recycling facility. He’s remembered as someone who immersed himself into skateboarding and art. But a few years before his death, his family and friends say, he was trying to navigate life with paranoid schizophrenia.

“He absolutely lived at WJ,” Strimple’s mother says. When he wasn’t writing, playing music or doing art, she adds, he was skateboarding.

He was beloved by the skateboarding community at Washington Jefferson, she says, pointing to a time he participated in a skating contest when was 15. He was so nervous, she says, that he decided to pull out during the second round of it. “Everybody just said, ‘No,’” she recalls. “Me and a bunch of his friends went over to talk to him and he decided to do it. And he won.”

Crespino remembers Silas bringing together old school skating styles popular from the ’70s and ’80s — when skaters rode their boards in drained swimming pools — with modern tweaks. But he had so much style, he adds, that you could be amazed just watching him move on his skateboard.

Drake says her son skated nonstop and was obsessed with the Zephyr skateboard team, the Southern California skaters from the 1970s who were among the first to adapt surfing tricks onto concrete with skateboards. At a very young age, she says, he watched the movie The Lords of Dogtown, which dramatized the Zephyr team, and he was hooked.

The sound of skateboarding on their back patio, Drake remembers, was nonstop and sometimes a little bit too much for her. But now she says she would love to hear it again. “When I hear skateboarding, it makes my heart light and heavy.” She adds, “I love that sound now.”

While at the skatepark, Silas would spend time helping out with children new to skateboarding, showing them where to put their feet on the board. “He really likes kids and wants them to skate,” she says.

Drake says her son developed paranoid schizophrenia suddenly. “He would say, ‘Mom I really want to go to the skatepark, but my friends are going to think I’m acting weird,’” she says. “I would tell him that it would be OK.”

If Silas had some mental health resources and courses in junior high school and high school, it may have been helpful for him in understanding himself, she adds. “I wish kids and adults had the words to say,” she adds. “If they had been taught that in school, it wouldn’t be so stigmatized and they would feel comfortable. And that would’ve been really huge for Silas.”

Silas moved to Austin shortly before his death. He wanted to move there for a while, Drake says, and he was in a band with a friend who was in Austin. But he wasn’t able to stay safe anymore, she says.

Drake says now she’s working on the justice part of his death. Strimple was the fourth person to die at the Austin recycling facility since 2015, according to an April 23, 2021, article by the Austin American-Statesman.

“They didn’t do anything about it, and I don’t think that’s right,” she says. “It’s Texas, and they’re just saying he was trespassing.”

‘He was so much like sunshine’

On Vara Perron’s left arm is a tattoo of a skateboard surrounded by dollar signs that says “all for money,” a reference to her boyfriend Ben Moody.

“The image came to mind after his death,” Perron, 16, tells Crespino as he delivers four Moody memorial decks with “Money Jones” emblazoned on it.

Enlarge

Crespino says Ben’s father, Andrew Moody, wanted to name him Money Jones Moody, but he couldn’t convince Ben’s mother. The parents settled on Ben (as in the $100 bill), and ever since he could talk he went by Money Jones.

Ben Moody’s death, and how his friends are processing it, has shown the lack of mental health resources for high school students.

“Anytime I mentioned self harm because I was worried about him, he would always say, ‘That’s crazy. Why would you ever go to that? It’s just wintertime and I want it to be summer,’” Perron recalls. “It just feels like a really big problem that intensely needs to be resolved, right now. But there’s no way.”

Ben Moody grew up in a skateboarding family, says his brother Drake Moody, who’s pursuing skateboarding in San Francisco. The sport was a big part of their upbringing; their mother would take them to WJ Skatepark, and their father would take them on camping trips that combined visits to skateparks in other cities.

At 13 years old, Drake Moody says, Ben began going to skateparks by himself, a sign that he was ready to pursue the sport seriously. “That’s when I saw that he’s fucking with it,” he says. “This isn’t just my dad’s influence and my influence on him. He’s actually making his own decision to go to the park and learn these tricks.”

Drake Moody knew Ben would be good at skateboarding ever since he first started as a toddler because of their skateboarding family, and as he skated, he got “fucking good.” Ben became a skater who excelled with the technical tricks, his brother says. Through foot kicks and shuffles, Ben could land various tricks that involved flipping the board. “He had the tricks.”

When Perron and Ben began dating in 2021, she says among the things they did together was going to WJ Skatepark together. “He was so much like sunshine,” she remembers.

Perron and Ben Moody’s one-year anniversary was March 11. On March 10, she remembers waking up to the news from his mother that he had died. “It felt like my soul was being ripped out of my body,” she says. “I genuinely felt just like a hole. I couldn’t breathe for a couple of hours.”

She didn’t go to school that day, but when she did return to South Eugene High School, she found it difficult to concentrate. Aside from two of her teachers, she says there weren’t many resources available for her to process mourning Ben.

After Ben’s death, Perron felt overwhelmed with high school gossip about her and Ben and with schoolwork. She says her yoga teacher gave her a meditative final exam to get away from everything: tending plants in a mini greenhouse. And her free period teacher helped her catch up on late classwork.

When Ben had told Perron that he wanted professional help, she says she and his mother couldn’t find any available therapist.

Ben’s mother called the high school counselor, Perron recalls, and that made Ben mad. Counselors don’t care about a student’s wellness, Perron says, and most of them aren’t trusted by students. “They have a stigma about lying about what they tell,” she says of the counselors.

What Perron would like to see high schools have are courses about mental health, something more than just one day in health class. “Most of the things I’ve learned have been after Ben has died,” Perron says, giving White Bird Clinic’s Helping Out Our Teens in Schools (HOOTS) as an example. “I started going to therapy shortly before Ben died, and there are so many things that people should know and be aware of.”

She says there needs to be a class where students can learn about themselves and be able to communicate what they’re experiencing, but more importantly, to know how to be kind to each other.

Losing his brother Ben and his friend Silas Strimple has been catastrophic for Drake Moody. “It’s been pretty nightmarish,” he says. “When everything happened, I thought I was done for. I didn’t know what to do.”

Having a memorial — whether a bench or a skatepark addition — at Washington Jefferson, where skaters can sit down and look at photos of Ben and Silas, would be a way to remind people to be kind with each other and stay strong together, Drake Moody adds. “We lost some loved ones and we need to value each other.”

Pushing for the Cause

During the darkest months of the year, Crespino was in the midst of a depressive mood. And the 48-year-old skateboarder says it could have ended in two ways: Either he could give in, or he could climb out of his depression.

He was able to climb out. He helped organize a May 21 skateboard contest fundraising for park repairs. And that was where memorial decks for Silas and Ben were first made, which were given to their family.

When the skateboard community saw the boards, it inspired Crespino and others to ramp up their production and sell some to raise money for a memorial at WJ Skatepark. “People were really excited for the boards, asking where they could get one,” he says.

For the past month, Crespino and another skateboarder, Ethan Hall, have been reproducing more memorial decks, and he’s been driving them to people who’ve bought them. He jokes that he’s become a skateboard Santa Claus. But the best part of it all is that he gets to see so many people in the area who have been touched by Silas and Ben.

Crespino says he’s hoping to raise $20,000 from the memorial decks and from donations. With that money, he says he wants to install a memorial for the two skateboarders. At first, he says he considered a city of Eugene memorial bench, which costs around $5,000, but he’s concerned that someone would steal the plaque on it. Crespino and other skaters don’t know what the memorial will look like or its function in the skatepark, but he says Silas and Ben would want it to be something skatable and part of the skatepark.

City spokesperson Kelly Shadwick says Eugene’s memorial options in parks are limited to its commemorative bench program.

But before a memorial is installed, Crespino will skate down to San Francisco. He’s planning to talk with as many people — and as many media outlets as possible — to advocate for mental health awareness as he makes the 831-mile trek. He expects the trip to last about a month, as he’ll skate from WJ Skatepark to Florence and then down the Pacific Coast Highway.

It’s a trip that he says will be a positive way to memorialize the loss of Eugene’s skateboarding community but also a way for the survivors to move forward.

“It’s our goal to make people aware about Ben and Silas, what they represent, but it’s more than just them and their memory,” he says. “The community needs to recover. The other kids left behind might be feeling they’re at the end of their rope in this day and age and feel like they have no one to turn to. We’re going to show up in this way so that we’re visible and do something by example.”