Kyrie Ackley leans out of her tent, six feet off the Fern Ridge Trail, not far from where Bailey Hill Road crosses Amazon Creek. The night before, she’d pitched the tent — green, shrouded with a black tarp and pressed against a corrugated metal wall and barbed wire fence.

Now, just before noon, Ackley has been told to leave.

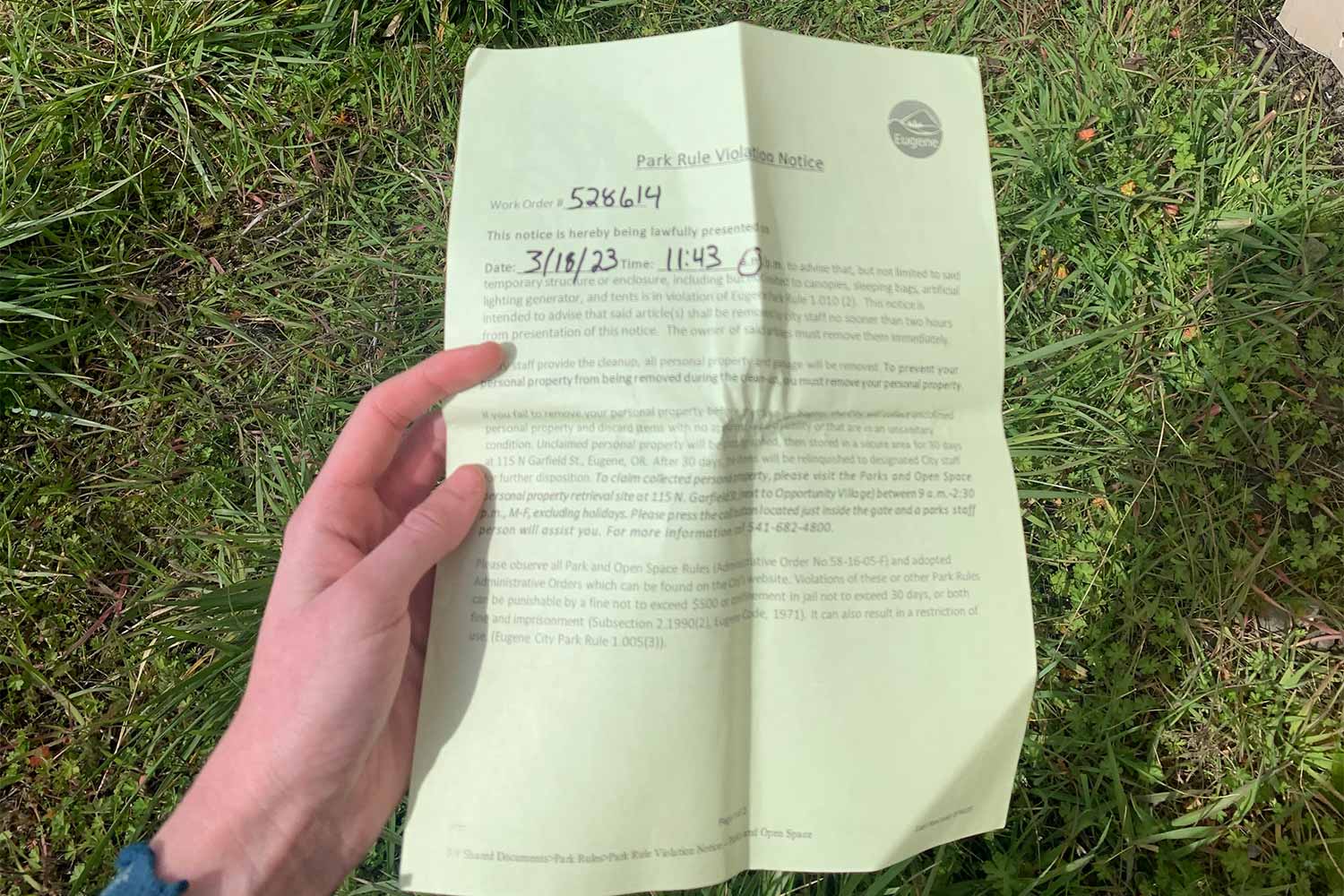

Ten minutes earlier, a city worker handed Ackley a notice declaring that her tent was prohibited and that she must take it down. Immediately.

Ackley points to the green paper, which she had folded neatly into quarters and placed on the grass next to her dog, Golly.

She’s been forced to move many times. Two hours from now, city workers will haul away her belongings if she doesn’t clear out. When she speaks about what she’s lost before — clothes, a backpack and medications for epilepsy — she cries.

“It’s just really hard. I’m out here by myself,” she says, her voice fading. “I always get like this after having to move all the time.”

Ackley recalls when the city gave her and other unhoused people ample time to take down their tents and move. But no longer.

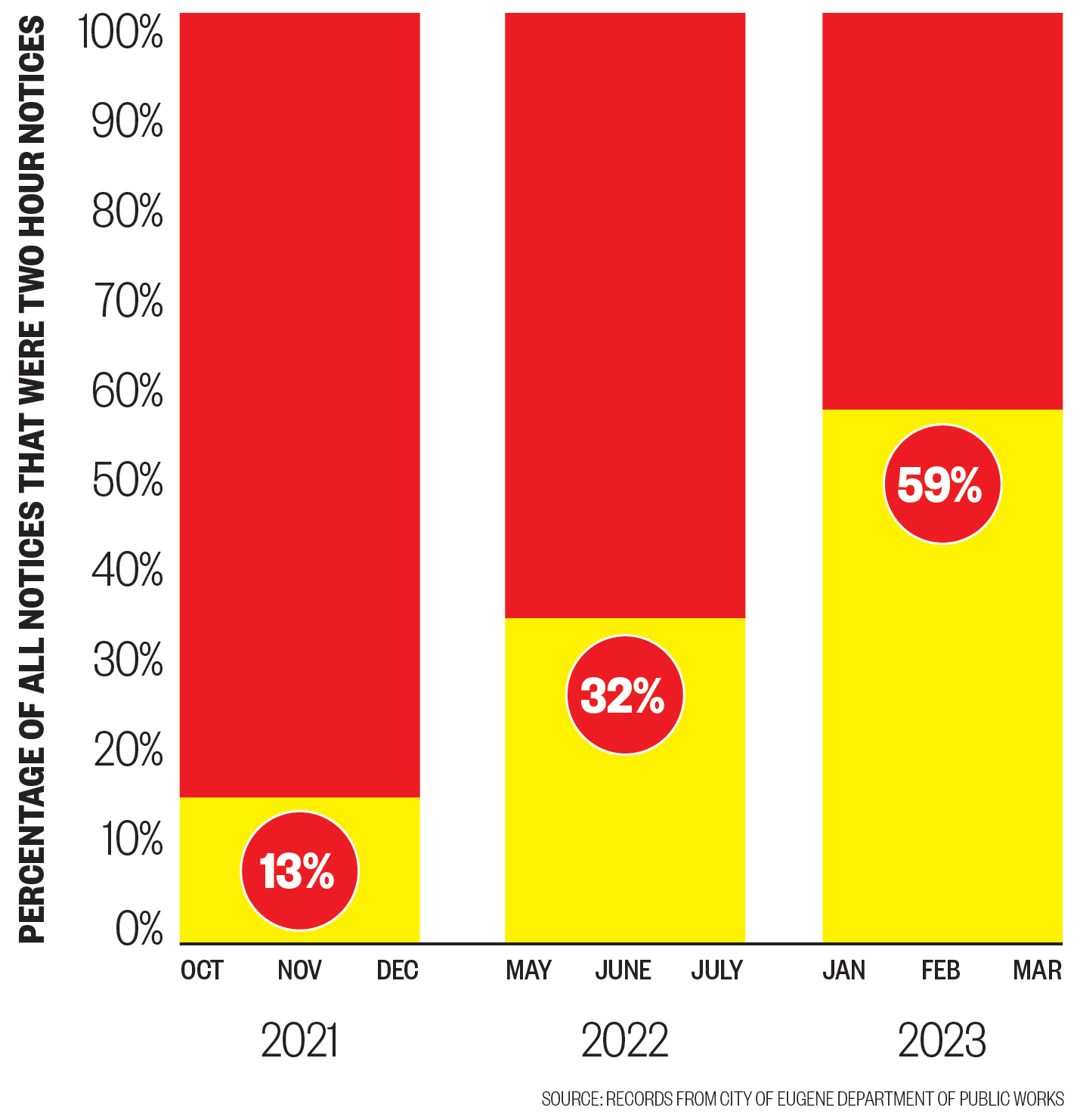

Since October 2021, city workers have issued nearly 1,400 notices to unhoused campers that they had only two hours to dismantle their shelters or have city workers haul away their possessions, according to an analysis of city documents by Eugene Weekly and the Catalyst Journalism Project.

More than half the notices city workers now serve are rapid evictions, city documents show.

Eugene officials are exploiting a loophole in a 2021 state law requiring cities give a 72-hour notice to unhoused campers before forcing them to move.

Oregon law doesn’t require cities to give a notice if people are camping in public parks. But Eugene’s actions have reversed a long-standing city policy allowing people camping in parks to have a 24-hour or 72-hour notice before being evicted.

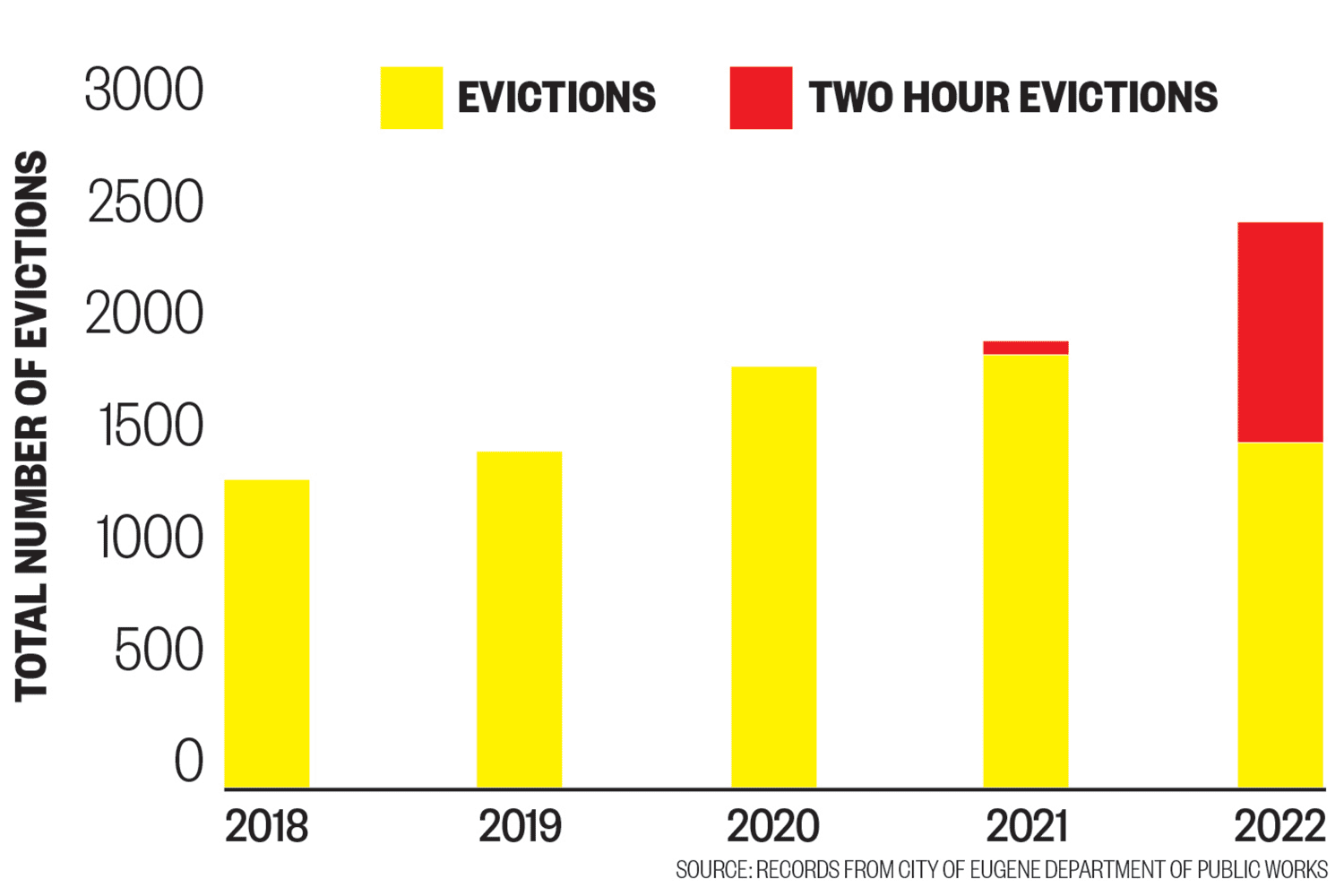

The city’s changed strategy helped drive the number of evictions of unhoused campers in 2022 to a seemingly all time high: 2,473, a 36 percent increase in just one year, EW and Catalyst’s analysis shows.

Meanwhile, city officials hid the dramatic change in the way it treated unhoused people. City officials acknowledge they made no public announcement of the change, nor did they bring the matter before city council.

Even Mayor Lucy Vinis says she didn’t know about it.

Vinis told EW after a Monday, April 10 City Council meeting, that she was unaware that since 2021 the city had been ordering unhoused campers to pick up and move within two hours or face losing their possessions. She says she’s also unaware of the increased use of the two-hour notices.

“I don’t know the level of criteria, what bumps something into a shorter term notice versus a longer term notice because I’m not at that operational level,” Vinis says.

Eugene City Manager Sarah Medary did not respond to requests from EW to explain why the city made such a dramatic change in its treatment of unhoused people and did not inform the City Council or the public.

Cambra Ward Jacobson, communications director for the city, says in an email the city doesn’t typically announce changes to procedure in how staff address existing rules and code and that there was no legal requirement to inform the City Council about the two-hour notices.

Heather Sielicki, a homeless advocate on the city’s Human Rights Commission Homelessness and Poverty Workgroup, worked to help pass the change in Oregon law requiring a 72-hour notice before forcing unhoused campers to move. Sielicki says advocates argued — and state legislators agreed — that the previous 24-hour notice often denied people time to move their belongings or gain access to shelter, health care or other necessities.

Sielicki says she’s shocked to find out the city had moved in the opposite direction — slashing the warning time from 72 hours to only two — and that city officials had hidden this from advocates and the public.

“This really stands to violate a lot of the principles of human rights, rather than trying to come up with concrete and productive ways to get people back into somewhere safe,” Sielicki says. “It’s just plain cruel.”

EW and the Catalyst Journalism Project examined more than 8,800 work orders from Eugene Public Works that document each time city workers force unhoused people to take down their camps and move. The city released the records in response to a request by EW under the Oregon public records law.

Dan Bryant, executive director at SquareOne Villages, which provides cost-effective housing to those in need, says he had not been aware of the two-hour eviction notices before being asked about them by EW. Bryant says such a short warning time is unreasonable, given that many unhoused people leave their camps for the day and might not see the notices before city workers take away their possessions.

“If they’re putting that notice with no confirmation that the person has received it, that’s a problem and should be stopped,” Bryant says “It’s one of the biggest issues that unhoused people face — losing their belongings.”

The revelations come as the Eugene City Council considers changes to city camping policies in light of a 2021 state law that requires local ordinances to be “objectively reasonable as to time, place and manner with regards to persons experiencing homelessness.”

At Nightingale Hosted Shelters, Conestoga-style huts for unhoused people located near East 34th and Hilyard, Nathan Showers says he’s been hearing about the two-hour notices for several months. Showers, a camp manager at the site, says the city’s ramped-up evictions are inhumane.

“The whole issue here,” Showers says, “is our city policies and our government need to figure out a solution not just move us around and try to hide us in deeper spots.”

Breaking a precedent

Former state Sen. Frank Shields, D-Portland, says giving unhoused people only two hours is unreasonable. “Government has to inject a certain amount of humanity into its decision-making,” he says. “And sometimes bureaucrats don’t understand that.”

Shields should know. In 1995, he introduced the first law requiring that cities provide a 24-hour notice before forcing unhoused people to move from their encampments on public property. At the time, police and city officials were not required to give any warning before confiscating unhoused people’s tents, sleeping bags and other belongings.

“Generally, my feeling was anytime you’re going to disrupt somebody’s life, whether there’s an individual family or a whole community, you need to give them a heads up, you know, like a 24-hour notice,” Shields says.

The 1995 law exempted cities from issuing 24-hour notices if the prohibited camping was taking place in a “day use recreational area,” such as parks or open spaces. The law also said the 24-hour notice applied only to “established camping sites,” even though lawmakers never defined what “established” meant.

Nonetheless, documents show, the city of Eugene for years routinely extended the 24-hour notices to unhoused people camping in city parks.

In 2021, lawmakers extended the notice time to 72 hours after concerns about how some cities swept large homeless encampments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Homeless advocates said 24 hours didn’t give many unhoused people enough time to find a place to stay or attend to their health needs. At the time, Eugene’s forced clearance of large homeless encampments drew protests.

State Rep. John Lively, D-Springfield, introduced House Bill 3124, which made the change.

“Part of the goal of this was to give time for the nonprofits to go out and work with these people to help find another location to protect their belongings, to set up a process to help them,” Lively says now. “And they thought that the 72 hours provided enough time to do that.”

The bill made no change in the law when it came to established camping sites.

Kelly Shadwick, a spokesperson for Eugene Parks and Open Space, said city officials in 2021 looked more closely at the law.

“It does not define the word ‘established,’” Shadwick says in a prepared statement in response to EW’s questions. “The city of Eugene’s interpretation is [that] a site set up for less than 24 hours is not established.”

Without public discussion, city officials invented a new kind of eviction for unhoused people: a “non-established camp” notice. The notices ordered that people take down tents or other structures immediately and that they remove their possessions within two hours.

Shadwick did not answer EW’s question about when the decision to start using two-hour notices was made. City Manager Medary declined to answer questions about how the decision was made, or why city officials came up with a two-hour notice after having allowed 24-hour notices in parks for years.

Documents show the first “non-established camp” two-hour notice was delivered on Oct. 28, 2021, to the owner of a camouflaged tent and shopping cart in Washington Jefferson Park. After that, the number of two-hour notices grew rapidly.

Meanwhile, Eugene officials were telling a very different story about their treatment of unhoused people on the city’s website.

In a section called “How We Respond,” the city’s website described how it handles prohibited camping in parks: “Staff provide a 72-hour warning and will return no sooner than 72 hours to clean the site.”

The city belatedly changed the website in March 2022 to say tents pitched in city parks had to be taken down immediately. By then, city officials had evicted more than 200 campsites with two-hour notices.

Sielicki was on the Eugene Human Rights Commission at the time the two-hour notices began. “I don’t remember anything like this ever coming up for discussion,” she says. “And I think that we had established a lot of trust at that time, and I wish we could have had a real open conversation about it.”

Mayor Vinis isn’t the only member of the City Council who didn’t know about the changed treatment of unhoused campers.

City Councilor Emily Semple says she had never heard of the “non-established” camp notices. “I don’t know anything about these two-hour notices,” she says. “That’s news to me.”

On the night of April 10, the City Council heard a plea for mercy from an unhoused person, whose letter was read aloud by a community member during the council’s public forum. The unhoused person wrote that he and other people camping in Eugene over the last 18 months have seen city workers provide little or no notice before clearing people’s camps.

“On four occasions in the last year,” he said in the letter, “a parks department vehicle has stopped at my tent site and removed my belongings, moved them to presumed storage sites. On each of these occasions, I’ve been left with nothing — no bedding, no tent, no private amenities — including toiletries, no clothing, and none of my personal records and papers. All four times I have had to start gathering once again the supplies and necessities for bare survival.

“The many others who have been through these ordeals as I have are joining together with me in strongly asking [for] at least 72 hours’ notice while being given the dignity, empathy and respect we expect as citizens.”

Enlarge

‘They’re gonna find me’

EW interviewed people living along the Fern Ridge Creek Trail in February and March who have also been forced to pack up and move their camps within two hours.

In February, Daniel Fisher, who has been homeless for several months, was pushing his shopping cart along the Fern Ridge Trail filled with his possessions when one of the wheels broke. He says it was so frigid out, he just couldn’t keep moving. He camped for the night and woke up to a city of Eugene worker telling him he had to collect his things and get moving — now.

Fisher, who says he became homeless after losing his job as a taxi driver, was confused because he thought people camping had 72 hours to move their belongings.

“When I got the two-hour notice, I thought it was a 72-hour notice,” he says. “But when I saw two hours, it did stress me out. It made my anxiety shoot up because pretty much all my stuff — in two hours, if I don’t have it moved, I don’t know what they’re gonna do with it.”

He’s since heard about the two-hour notices elsewhere. “I see the shift happening,” Fisher says. “They’re putting two-hour notices up. This is all in the last month I’ve seen this.”

Fisher says he typically sleeps in parks during the day and keeps moving all night so he doesn’t have to pitch a tent. “I’m afraid everywhere I set it up,” Fisher says. “I’m considered trespassing or I’m basically exposing myself to a legal consequence. “I’m getting two-hour notices because I’m walking until I cannot walk anymore.”

Bonnie “Rae” Steiner says she was camping in February underneath a footbridge along the Fern Ridge Trail with friends when city workers in a truck arrived and told them they had two hours to move their things.

Steiner says she has lived on the Eugene streets since the mobile home she lived in burned down in the 2020 Holiday Farm Fire. She’s 64 years old and has lupus, which makes moving her belongings difficult.

She says she didn’t know where city officials wanted to move her things to in that short time. “They stood there while you tried to pack what you could,” she says of the city workers. “It’s very embarrassing.”

Steiner adds that she tried moving her things far away enough from underneath the bridge, but, after the two hours passed, the workers took her items.

The city stores the personal property it takes from unhoused people for 30 days. People can reclaim their items by visiting the retrieval site, which was about two miles from Steiner’s campsite that day.

Steiner says she’s lost all her belongings to two-hour notices many times, but she never retrieves her items from storage since it’s difficult for her to walk the roughly two miles to the storage center and carry all her items back.

“Well, once you get there, how the heck are you gonna pack it?” Steiner asks.

Some of these notices are handed out in the early evenings and on weekends. But the personal property retrieval site at 115 N. Garfield Street, where items deemed valuable are stored and available for pick-up within 30 days, is closed on weekends and after 2:30 pm on weekdays, leaving some people without tents or sleeping bags for a night or weekend.

Enlarge

Kyrie Ackley, who wept after receiving her two-hour notice, says she has been unhoused and living in parks for several years. She says she’s lost her belongings six times to two-hour notices. One of the hardest items for her to lose was food for her dog. “My dog eats before I do,” she says.

She says she has felt the full weight of the two-hour eviction notices. “They go by here, like, every day, or every other day, and I get lucky if they don’t see my tent,” she says. “They only give you two hours. They used to give you 72 hours.

“Every time I get a notice, I’m like, ‘Fuck, they found me.’ But I already know that they’re gonna find me,” she says. “Why can’t they just let me be here for at least more than one day?”

This story was developed as part of the Catalyst Journalism Project at the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication. Catalyst brings together investigative reporting and solutions journalism to spark action and response to Oregon’s most perplexing issues. To learn more visit CatalystJournalism.uoregon.edu or follow on Twitter @uo_catalyst.

How We Reported This Story

By Alexis Weisend

Eugene Weekly and the Catalyst Journalism Project spent four months examining more than 8,800 work orders filed by the Eugene Department of Public Works from April 2021 through March 2023. EW and Catalyst obtained the records under the Oregon public records law.

These work orders document how city workers deal with the clean-up of prohibited campsites, even if there is only a single tent involved. Nearly 4,400 work orders show that city workers served a camp clean-up notice, forcing campers to move at the risk of losing their possessions. These work orders include reports of city employees’ actions, photographs of the prohibited campsites and images of the clean-up notices.

EW and Catalyst undertook this reporting to see if Eugene officials had changed their policies since the COVID-19 pandemic, when the city officials launched what then appeared to be an all-time record number of evictions of unhoused campers. At the time, Eugene officials denied their actions conflicted with Centers of Disease Control and Prevention guidelines regarding unhoused people sheltering in place. City work orders showed otherwise. See “Swept Away,” EW, June 17, 2021.