“I can’t believe I’m actually hoping some of the kids on my caseload will land in jail. It’s the only way in our system they’ll ever get the services they need.” We have heard this statement from adults concerned about youth unable to access behavioral health services in this community for more than 20 years. Yet despite many promises from elected officials, people of all ages still cannot access the behavioral health care, including addiction treatment, they need.

A “yes” vote on the current jail levy may fund programs for a few incarcerated teens and adults, but it also says yes to a system that does not address root causes and is not an effective community safety policy. This is why we volunteer for Healing Not Handcuffs, a community coalition that opposes the levy.

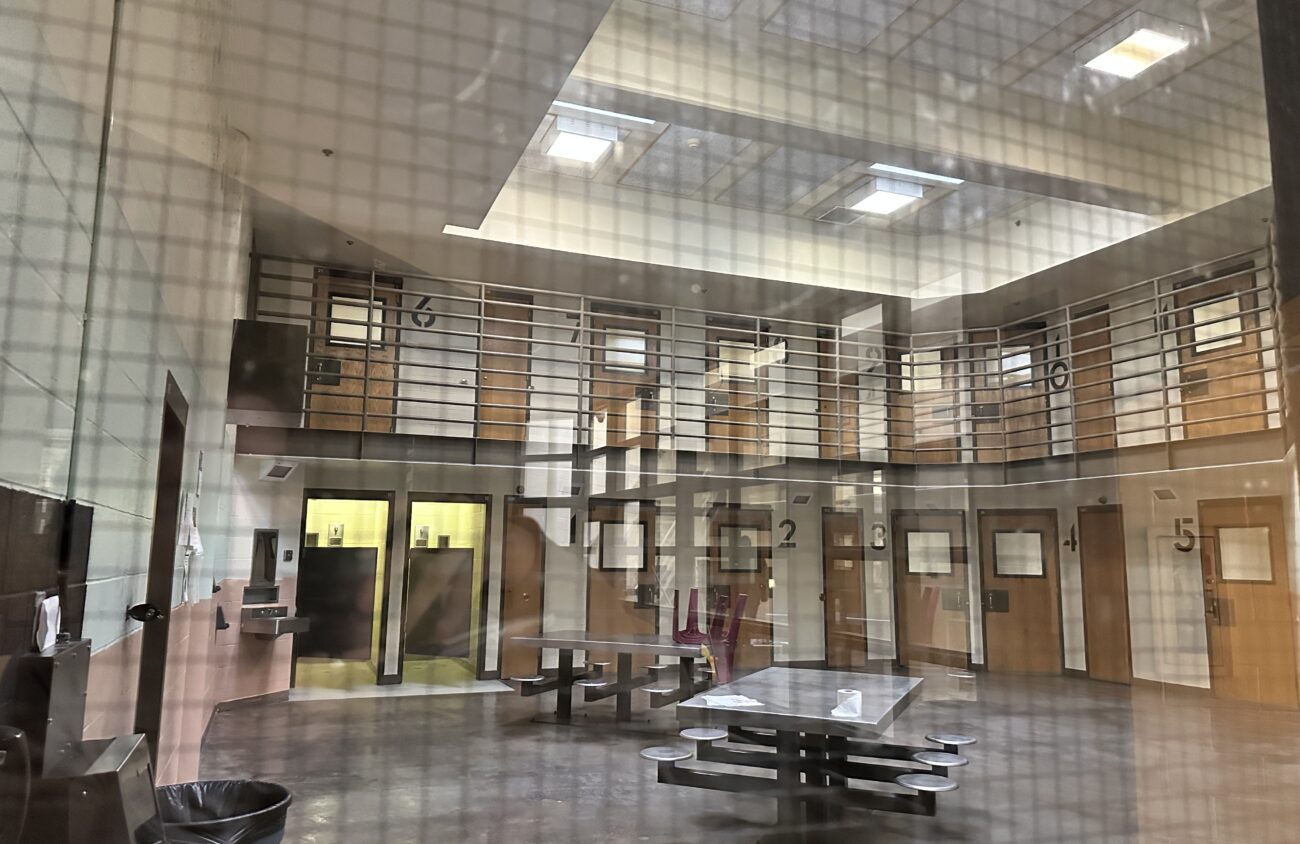

Half the people in Lane County Jail struggle with mental illness and/or substance addiction. In the National Survey on Drug Abuse and Health, Oregon last year had the second highest substance abuse rate in the nation, yet ranked last in access to treatment. Lane County budgeted $36 million for the jail last year, not including court and arrest costs. With 260 beds in use at the time, that meant $11,500 per month just to keep one person in a jail cell.

Those funds, if spent wisely in the community, could pay for mental health treatment, addiction recovery programs and youth development projects that would support many individuals toward wellness. Without services in the community, mental health programs in the jail make no sense.

The fear-based story that the jail is our most valuable resource for ensuring community safety is a myth. Researchers at the Prison Policy Initiative demonstrated that in 13 communities that initiated pretrial release programs, crime rates decreased or held steady once the pretrial release program began. Violent crime did not increase 10 years ago when reduced jail funding resulted in capacity-based releases in Lane County.

And, with decriminalization of petty drug crimes under Measure 110, pressure on the jail capacity will continue to drop, while we expect to see the expansion of addiction treatment programs as funding from the program reaches our communities.

Decades of research have shown that jails and prisons don’t reduce criminal activity. People are safer in communities where poverty is rare and basic needs are met, yet we fund jails and begrudge funds for affordable housing, adequate health care, education and economic opportunities. We cannot accept the myth of innocents and “thugs,” fueled by politicians manipulating white fears, any longer. As we see hate crimes increasing and gun violence in the news daily, instead of accepting the false promises of punishment, we should reject narratives of fear and retribution and courageously invest in healing and strengthening our communities.

Municipalities all over the country are experimenting with restorative justice, which addresses accountability through consequences, not punishment. Consequences could mean loss of power and privilege or paying for medical and recovery costs for someone you harmed. Restorative justice is not “one size fits all.” It puts the needs of the people harmed, and their families, at the center of each process.

Restorative justice harks back to Indigenous practices, and is growing in Lane County. The county has an restorative justice program already in place that works in tandem with the Circuit Court. The district attorney determines who can use restorative justice so only a few offenders and victims have access. Conflict Artistry, LLC, is another local site of restorative justice, inviting community members to access their program directly, prior to resorting to police and prosecution. If more community members were willing to attempt a restorative process and let our leaders know, we might experience true accountability and repair from harm.

Saying “no” to the levy is only a first step, to admit that the system we have doesn’t make us or our children safer, and, more often than not, harms those caught up in it, as well as their partners and children. We must also invest in the care and services people need outside the jail. To create a community where the largest number of people possible can enjoy health, safety, dignity and belonging, we will have to step up with courage and a willingness to experiment. Compassion and reason point us in the direction of community-based rather than jail-based initiatives.

Ellen Rifkin and Rose Wilde are volunteers with the Healing Not Handcuffs Coalition and the Springfield-Eugene Chapter of Showing Up for Racial Justice, more at HealingNotHandcuffs.org.