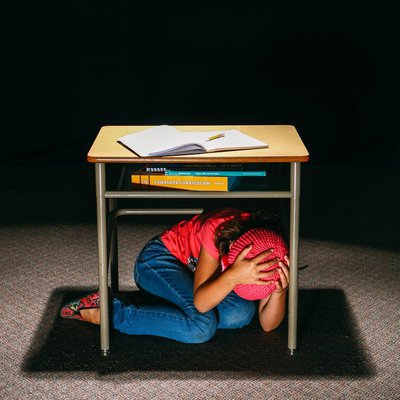

It happened on a typical school day with no warning. As the 7.9 magnitude earthquake started shaking the ground, students were crushed and killed inside their own schools when the buildings collapsed on top of them. According to CNN, 5,335 students died or went missing after the 2008 earthquake, with even more left disabled. While this particular earthquake happened in southwestern China, the same thing could happen in Lane County to old school buildings like Edison Elementary.

In China, thousands of deaths were attributed to instability of school buildings. Many were built decades before national building codes took effect, and even then, a 2008 article from The New York Times suggests that application of the code to school buildings was not always enforced. This lack of preparation was a poor excuse to the devastated parents who sent their kids to school, only to have them never come back.

Oregon, like China, has a long history of seismic events. While China is riddled with fault lines that trigger earthquakes, the Pacific Northwest also has a looming threat — the Cascadia Subduction Zone, where two tectonic plates intersect off the West Coast. The last mega-earthquake in Oregon happened in 1700, but geological records show that the Cascadia Subduction Zone produces mega-earthquakes on a recurring basis, about once every 500 years. According to Yumei Wang, a geotechnical engineer for the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries (DOGAMI), Oregon is due for a massive earthquake, one that could rival the 9.0-magnitude earthquake and tsunami in Japan two years ago.

“It’s 100 percent certain that a very big earthquake will occur on the Cascadia fault,” says Wang, who helped pass legislation in Oregon to propel earthquake preparedness. “The question is exactly when it will occur. But we’re guaranteed to have that earthquake.”

So, are Oregon schools ready? The answer, largely, is no. In 2007, DOGAMI published the Statewide Seismic Needs Assessment, which evaluated the seismic readiness of Oregon public schools and emergency services buildings. It used the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s system of rapid visual screening to give a quick, preliminary estimate of building safety. The study turned up some grim results — of the 2,018 K-12 public school buildings surveyed, 12 percent were rated at a very high risk, meaning they are very likely to collapse in a major earthquake, while 35 percent were rated high risk, with a more than 10 percent likelihood of collapsing.

And the study found that Lane County’s schools are no exception. According to the needs assessment, six schools in the 4J School District — Edison Elementary, Coburg Elementary (now Coburg Community Charter School), South Eugene High, Twin Oaks Elementary, Willagillespie Elementary and Winston Churchill High — have buildings that are at high risk of collapse in the event of a major earthquake.

The 4J School District received a $170 million voter-approved bond measure in May to use for facilities improvements. 4J plans to replace Howard Elementary, River Road Elementary and Roosevelt Middle School, with extensive remodeling to the Arts and Technology Academy and a small addition to Gilham Elementary. All of these schools were rated at moderate risk of collapse in the needs assessment. Ben Brantley, manager of the capital improvement program for 4J, says these buildings were chosen for renovation based on a 2012 report by MGP of America, a consulting company that evaluated 4J’s buildings and scored them in terms of building condition, educational suitability and other criteria.

Earthquake safety was not factored into the decision-making for building renovation. Brantley says this is because the 2007 seismic needs assessment did not take into account 4J’s previous work in seismic retrofitting of its buildings. In 1993, after the Scott Mills earthquake in Portland, the 4J School District used bond money to have its buildings evaluated in terms of seismic deficiencies. These evaluations were then used to prioritize life-safety retrofitting in the event of a moderate earthquake, including upgrades like bracing entrances and anchoring brick mortar to prevent it from falling down on people as they exit the building. The priority one upgrades are all complete, and Brantley says the district has no plans to further retrofit its buildings, unless it makes sense to do so during remodeling for other purposes.

Brantley says after DOGAMI released the high risk ratings for six 4J schools, he had structural engineer Scott Metzler evaluate the buildings in greater depth, and according to his work, they all fell into the moderate category of risk, although Edison Elementary is on the high end of moderate risk. The school, built in 1926, is one of the district’s oldest buildings, and a rating of moderate risk in the evaluation system used by the needs assessment indicates that the building has between a 1 and 10 percent chance of collapse.

“They’re better than DOGAMI thought,” Metzler says. “It’s almost impossible to bring older buildings to current codes. The goal is to keep the building standing up until the students get out.” He adds, “If we had a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake, I really can’t say what the outcome would be. All I can say is we did the best we could, given the constraints of cost and the current understanding of how earthquakes perform. Something is better than nothing.”

While the older schools have received seismic updates, they are not to Cascadia-level mega-earthquake standards. Because these retrofits started in the mid ’90s, they are not necessarily in compliance with the most recent building codes. “We don’t go back after the code changes because that’s really expensive and disruptive,” Brantley says. “We feel like we’ve done the priority one work, and we’ve done as much as we’re going to do of that.”

Many of 4J’s schools are aging and were built before 1971, when Oregon established its first statewide building code. While the most recently built schools are up to modern seismic standards, including Cal Young Middle School, Madison Middle School, Bertha Holt Elementary and César E. Chávez Elementary, the older schools are more difficult to fix. “We did what was recommended by structural engineers at the time, but you can’t bring these old buildings up to new standards,” Brantley says. “It wouldn’t be practical to do that.”

He says, “We were looking at bracing things and getting people out of the door safely in the event of a moderate earthquake. We can’t get there in the event of a 9.0.”

In 2005, the same legislation that required DOGAMI to perform the needs assessment also required that Oregon set up the Seismic Rehabilitation Grant Program, a “competitive grant program that provides funding for the seismic rehabilitation of critical public buildings, particularly public schools and emergency services facilities,” according to the program’s website. So far, the program has funded earthquake retrofitting for 16 Oregon school buildings, with eight more buildings in progress. Kiri Carini, grant coordinator for the program, says that the retrofits bring old buildings up to current American Society of Civil Engineers life safety standards, which factor in the risk of a Cascadia-level earthquake.

Legislation that passed during the most recent session allocated $15 million for seismic upgrades to public schools. Carini says that any public K-12 school, community college or university can apply for grant money.

The Springfield School District recently received a $255,549 grant from the grant program to retrofit Walterville Elementary School, which was built in 1952 and had a rating of “very high risk” in the DOGAMI study. Devon Ashbridge, communications specialist for the Springfield School District, says the district received the grant after applying twice, and part of the application process involved a $4,500 structural evaluation by an engineering firm in order to craft a successful retrofitting plan.

Without the grant, Ashbridge says, “We would not have been able to undertake this project. The grant allows us to do something that is outside the scope of what we would ordinarily be able to do, and that’s true of most schools in the state. For our district, that’s meant a huge decrease in the funding we have available for maintenance of our buildings, and we have a very restricted amount of money available for funds. That’s why we actively pursue grants like this — because we believe this work to be very important.”

Schools in the 4J School District have not received any seismic rehabilitation grants because the district is not applying for them. Brantley says he attended a seminar training session in Salem and decided that the cost of evaluating school buildings as part of the application process was too great.

“Even the simplest evaluations can cost $5,000, and it can get up to $30,000 for a fairly complex building,” Brantley says. “South Eugene High School is on pilings built over swampland, and that $30,000 may not have gotten us there. And you might get funded, and you might not get funded. What happens if we get an asbestos surprise? There are no increases to your grant. We’ve got bond funds; we’re just going to continue doing our own bond program.”

Carini says that evaluation costs can vary depending on the complexity of the building, but the grant program asks only for a preliminary assessment, a likely cost being between $5,000 and $10,000. “We have applications come in where schools have invested in a more robust engineering assessment, but that’s their choice,” she says.

Considering that the grant money provides hundreds of thousands of dollars for seismic retrofitting and turns “high risk” schools into “low risk” schools, investing money in an engineering evaluation seems a comparatively small price to pay. Kim Lippert, a public information officer for the Oregon Office of Emergency Management, says that while no amount of retrofitting can completely guarantee a building’s resilience in the event of a high magnitude earthquake, the retrofits make unsafe schools much safer.

For engineers like Wang, it’s all about protecting Oregon’s infrastructure and, more importantly, its people. “The goal is to get something done slowly but surely so it’s not that painful when we divert a small percentage of our funds to improve things,” Wang says of the statewide mission to prepare Oregon schools for a major earthquake. “After it happens, we will definitely wish that we did more. I’ve seen it all around the world. No one ever expects it; it’s always a surprise. But those who prepare well recover more quickly.”