After enlisting in the Navy at 19, actor Ben Buchanan, now 26, first trained in the stifling summer heat outside of Chicago. Later, crossing the equator, he experienced the traditional “shellback” ceremony, a 400-year-old naval ritual in which mere “pollywogs” are transformed into sturdy shellbacks. For Buchanan, this rite of passage included being shot at with fire hoses and crawling through garbage.

“It was pretty fun,” he says.

Buchanan served in Iraq and Afghanistan as a mechanical aviation egress specialist — the mechanic responsible for making sure the pilot can safely eject from the plane. For a kid who moved a lot growing up and never took much interest in school, it was a role he took seriously and played well.

Buchanan describes the ongoing wait for what he calls “exhibition combat” — watching enemy combatants walk down from the hills, usually in small groups of two or three. On base, Navy snipers at the ready, they’d watch as this week’s pair or trio would set up their rocket-propelled grenade launchers. “Because of the rules of engagement,” Buchanan says, “you can’t fire unless fired upon.”

And so they marked time, hours, sometimes days, waiting for an RPG to hurdle towards them.

“We felt safe enough,” he says. “It’s not like they’d come with 2,000 troops. After a point, you get a little used to it. It’s a desensitization.”

After catching minor shrapnel from a rogue RPG, recovering and then finishing his service, Buchanan was honorably discharged when his four-year commitment was fulfilled.

“They asked me to continue, but I didn’t have it in me,” he says.

Buchanan found his way to Eugene to be nearer his family, and to Lane Community College, paid for by his GI Bill. It was at LCC that Buchanan found his first acting class.

“I was a jovial kid,” he says. “But I came back subdued. It made you grow up fast.”

The journey of the military veteran has been shouted from the stage since theater began. The first recorded plays in the Western canon are about war, yes, but not about the glory and the spoils. On the contrary, the first plays in recorded history are about veterans.

Aeschylus wrote about a once-great king, so deeply wounded by his experiences in battle that he kills his own daughter. Sophocles created a bloody ruin in his character Ajax, a soldier trapped in traumatic memories of the Trojan War who tortures livestock before committing suicide. Great playwrights across the millennia have borne witness to carnage, allowing veterans’ stories to be heard.

Look to the stage today, peer behind the curtains, peek into the wings, and you’ll see military veterans of Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam and Korea, finding home, comfort, self, even meaning, in the theater.

Express Yourself

Expressive art therapies, such as dance, music, drama or visual art therapy, may help to release pain and quell some of the symptoms of stress, anxiety or depression in traumatized populations.

“Many veterans with PTSD report that engaging in art therapy fosters relief from symptoms such as flashbacks, emotional numbing and panic states,” says Annette Shore, a clinical therapist at Portland’s Returning Veterans Project and professor of art therapy at Marylhurst University.

“The creative process provides an outlet for expression and stress reduction,” Shore says. “While veterans are trained to maintain control and remain strong, art therapy allows them to access the nonverbal areas of the brain where traumatic memories are stored and to express their fears and pain as well as their hopes.”

Shore points out that building a sense of connection can be an important aspect of such therapies. “Art therapy groups provide opportunities for sharing distress and finding support and relief from the inherent sense of isolation and alienation that returning veterans may experience,” she says.

Inherently relational, dramatherapy seems an especially beneficial way to reach veterans.

Pioneered by Peter Slade in London in the 1930s, dramatherapy first developed as a means to reach underachieving, indigent children. Later, as Slade recuperated from injuries he sustained in battle during WWII, he began to apply these same theatrical techniques when working with his fellow vets.

Although evidence points to the efficacy of arts therapies in working with veterans, it’s possible drama needn’t be “therapy” to have therapeutic effects.

The Art of Knowing People

Acting classes, then, challenged Ben Buchanan to open up.

“I had a hard time being funny at first,” he says, recounting how he just couldn’t seem to do Mercutio’s famous Queen Mab monologue as a comedy.

Buchanan’s teacher, Judith “Sparky” Roberts, gently encouraged Buchanan to try the piece different ways, so he could find the funny in it. What finally cracked the code for Buchanan was doing the monologue in a Scottish brogue, to great success.

Using techniques designed to welcome all students, acting teacher Roberts was inadvertently creating a safe space for veterans to share their experiences and for their leadership and teamwork abilities to be validated and valued.

When Roberts directed Buchanan as Wilbur the Pig in 2012’s Charlotte’s Web, she recalls, “The veterans involved in the production enhanced every aspect of it.”

“The veterans were always on time, always knew their lines and they never made mistakes,” Roberts says.

“The goal of an acting class is to restore you to that childlike state of play,” adds Brian Haimbach, another of Buchanan’s instructors at LCC. “In acting classes, arts classes — in the performing arts — you’re accessing part of your soul. It’s going to be healing in a way.”

Mounting a play takes discipline, focus and the ability to take direction. But there’s more to theater than following orders.

“In a class, but especially in a play, you’ve got to bring something to the table, you have to make it your own,” Haimbach says, adding, “I’m not just a cog in a wheel. My input is valued.”

Buchanan began working in community theater and will head to Western Washington University in Bellingham this fall to major in acting for film and stage.

It’s not just his former teachers who appreciate him.

“As his director, I have always found Ben pleasant to work with, and he takes direction easily,” says Michael Watkins, who has performed with and directed Buchanan in several shows. “As a fellow actor, he looks you in the eye and lives in the moment, in my opinion, two of the most important aspects of acting.”

Buchanan says, “Theater, to me, is the art of knowing people, of knowing someone so well — deeply and intrinsically — not only could you take their place, you could be them, bring them to life, for audiences. Theater helps every day because it breeds in you a love of knowing people.”

Veterans needn’t be onstage performing to benefit from the theater. Helping behind the scenes serves to foster camaraderie, too, and for some, theater is a first step in the journey back to socializing with civilian life.

Robert LaFavor, 67, discovered the Very Little Theatre when he began volunteering in 1977. “I’d help out with stuff,” he says. “And watch a play once in a while.”

LaFavor was en route to Army basic training for the Vietnam War when a motorcycle accident left him paralyzed in both legs.

“There was a lot of us in the VA hospital,” LaFavor says. “We helped each other out a lot. There were friendships you formed. As soon as you think you’ve got it rough, you just look around you and there’s others who have it a lot rougher.”

LaFavor winces at the idea that his time volunteering for VLT somehow makes him special. “It’s a good thing for everyone,” he says. “It’s fun, there are good people there. It’s something creative. There are no downsides.”

James Kissman, 83, a Korean War veteran and VLT volunteer, say that “when people get out of the service, they feel restricted to a certain degree in social intercourse, because the civilian public doesn’t understand what frame of mind the military people have to assume. Theater brings you back into maintaining your position in society, to be accepted again. It gives you a feeling of confidence in what you can do.

“Theater prepared me to face things that most people are afraid to do,” Kissman says. “The basis for the training is discipline, how to get along and cooperate with the people with whom you work. You have to have that rapport with the other actors onstage.”

“The most meaningful part of veterans’ lives doesn’t have a place in public conversation,” says Jonathan Wei, executive director of The Telling Project, a national organization with roots at the UO that employs theater to deepen civilian understanding of the military and veterans’ experience.

Through a unique artistic and aesthetic experience, Wei says, many theater projects could foster interdependence and camaraderie, creating a safe space for expression and potential healing.

“Theater is a trick,” Wei says. “Whether it’s in an inquiry-based original piece or a Shakespeare play, theater is a contrivance. But that contrivance actually allows for a real conversation to take place.”

Abigail Leeder, registered drama therapist and director of the Experiential Education and Prevention Initiative at the UO, adds, “The expressive arts are a natural way for us to process our life stories, to step out of our everyday reality into other realms. It’s a humanizing experience. We’ve been doing it for thousands of years.”

Rules of Engagement

Veterans may have a fuller, more integrated appreciation of the world’s interconnectedness than those of us who’ve never experienced war. They’ve crossed a bridge, between here and there, between “us” and “them.” They’ve been strangers in a strange country.

As civilians, we may find ourselves compartmentalizing, even stigmatizing veterans, assuming somehow that they’re broken, damaged, that they’re fundamentally different from “us.” But civilians don’t have to see or understand certain messy realities about the world. We can go about our day, driving here and there, going to work, shopping, not really thinking about how our actions relate to a global stage.

Veterans’ experiences, on the other hand, have pierced the bubble of everyday life’s contrivances, and some carry that rupture with them wherever they go.

“Nobody told me I could do scholarships and avoid delayed entry,” says Ryan Olson, 37, who served in the Navy during the Kosovo War. Olson had enlisted at 17, between his junior and senior year of high school. Despite excelling at track, he didn’t understand that he could put off basic training if he secured the financial support to start college.

“I went to Portland for my ASVAB test,” Olsen says of the multi-tiered aptitude test used for placement in the Navy. “They told me my scores were good, and that I could either be a lithographer or a builder. I didn’t know what a lithographer was, and I was 17. I figure I like using my hands, so I chose builder. What I didn’t understand is I’d be doing construction in a combat unit.”

After three months of basic training, Olson went to Builder A school, where he was taught the fundamentals of carpentry. “We basically built a house,” he says.

Then he caught up with an “NMCB3,” a Naval Mobile Construction Battalion, in Guam. There they engaged in field exercises, or “FEX” — playing war games against the Marines. Firing assault rifles loaded with blanks, playing laser tag in the jungle, “It was like an awesome camping trip,” Olson says.

But he soon came to understand that he would have to get used to real mortars, rifle fire and patrols. “I realized we’d learned the basics of construction, but it’s all under combat duress,” Olson says.

And it was during FEX that Olson first hallucinated from lack of sleep. “Sleep deprivation is part of the training process,” Olson says. “They’re breaking you down, like melting clay, so they can let it harden and mold it into what they want.”

When he was finally deployed overseas, “I was taking it seriously,” Olson recalls. He found himself in Kosovo, transferred to a security unit responsible for checkpoints, convoys and checking cars for bombs.

“This is some serious business,” Olson remembers. “And I’m not gonna die, and I’m not gonna let these guys die.

“Kosovo was crazy from the beginning,” he says.

Olson was first out of the helicopter on arrival in Kosovo, only to learn that their landing place had not been swept for mines. Orders were radioed in: “Don’t move.”

Their first camp was in “a warehouse, blown to shreds,” Olson says. “It was still smoking.”

For five months straight without real rest, Olson provided security for more than 100 convoys.

“I’d wake up, make sure my rifle was ready, that I had enough food for the day,” Olson says. “They could tell I was getting a little tense.”

Olson’s lowest moment still wakes him up at night.

“I put two kids on the ground,” he says. A father now, he’s haunted by his actions. “I made them get on the ground, open their bag. They were selling CDs. I ended up buying two CDs. I cry about it all the time. They just wanted to make money,” Olson pauses. “But here I am.”

Diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, agoraphobia, panic disorder and anxiety, Olson lives on disability benefits.

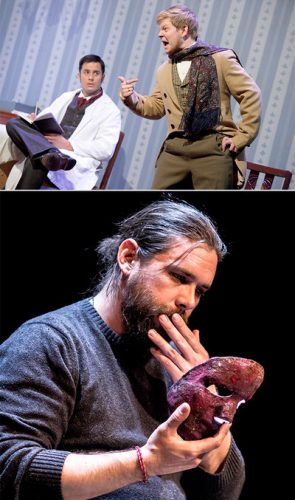

Ten years ago, he started classes at LCC with Sparky Roberts and Patrick Torelle, who is also a veteran. When his GI Bill ran out, Olson started working in community theater, most recently in a piece in Oregon Contemporary Theatre’s Northwest Ten series.

“Theater is the most controlled environment I can think of,” Olson says. “Because of all the rehearsals, we know where we might foible at or have a moment of weakness, and we know we’re going to be OK.

“You have to look people in the eye,” he says. “At first it’s uncomfortable to open up, but you get used to it. You get adrenaline — a rush.”

For the Northwest Ten, Olson played a vet seeking social services.

“Theater let me play characters that would allow me to get the anger out, the heartache, or the pain. It wasn’t like a counseling session. But I needed it. It was so important to play these roles,” Olson says. “Theater introduced me to meditation. Everything I do to relax myself is all theater exercise.”

Pointing to the continuing pain he’s suffered from participating in a war without clear motivations, Olson recalls, “None of these people fucking like us, none of them want us around. You’re not safe anywhere.”

He continues. “I don’t know how to help people understand that. I can’t even get them to understand that I can’t leave the house.”

All the World’s a Stage

Like a Greek chorus — the group of voices in Greek drama who chant commentary on the characters’ struggles — older vets describing their experiences bring gravitas, the weight of memory, as they look back on their younger selves and choices made and lived with.

“We were all lost and waiting for Godot, or waiting for something,” says Richard Leinaweaver, 84, who served in the Air Force during the Korean War and volunteers for the Very Little Theatre. After the war, Leinaweaver attended the American Academy of Dramatic Arts and earned his Ph.D. in theater from Michigan State.

“When you study history,” Leinwweaver says, “you’ll find that WWII is the last kind of justified war. After that, these conflicts have been crooked, unjustified, with a weak premise.

“If vets come home and realize how they were used,” Leinaweaver says, “it can leave a vet feeling demoralized.”

Theater may offer some relief.

“What you get to do onstage, in rehearsal and performance, is you get to be somebody else,” Leinaweaver asserts. “You’re figuring it out for another character so you’re not putting yourself in danger.”

And theater training might help mask the pain of re-entry into civilian life.

“If I can walk into a bar, I can be me, or I can be some other guy, and you would never know.”

It’s easy to fall into imagining theater as a panacea. Because it’s intrinsically communal and interactive, theater has the capacity to create a path back into civilian life. But the artifice inherent to the activity itself could seem as fragile and hollow as any other societal contrivance, to someone who has spent time on the outer edges of humanity.

“Everyone starts with a clean slate,” says Chris White, 32, a Marine veteran of the Iraq War, who performs and works behind the scenes throughout Eugene theater. “They shave your head, take your personal effects, your perishables. You have no family, no friends. You’re a jarhead.”

White pulls no punches about his time in the service and how he got there.

“I was an uneducated, naïve kid,” he says.

Moving a lot as a child, White says no one noticed he couldn’t read until he was in the tenth grade. And despite a family with a military background, White says he didn’t really fit into the service once he enlisted.

“I wasn’t ‘Oorah!’” he says, the traditional Marines battle cry. “I just kept my mouth shut and did what I needed to do.”

In Iraq, White slept for months in the dirt, with no electricity, phones or toilets, and only non-perishable dry food. On convoys to and from bases, sleep deprivation and concomitant hallucinations were routine.

“Theater allows me to be somebody I’m not, to use the emotion, the anger and the sadness, to use it and to get applause,” White says.

White performed with Ben Buchanan in Charlotte’s Web and served as that production’s stage manager, even jockeying from his backstage position to play multiple roles onstage. The responsibility came easily, White says. It was all just part of his training.

As a stalwart volunteer throughout the theater community, White is respected for his work ethic and talent. Though he says he appreciates the mutually respectful relationships within the theater, he says, “I don’t feel ‘safe’ in theater and I don’t feel like I’m a part of it. I do things for people who ask me, but I don’t feel like I fit in.

“I’ve seen poverty,” White says. “I’ve seen bad things, and by me jumping into social gimmicks or running away from my problems — it’s a group, like a book club, or the Marine Corps, theater is the same thing. You feel like you know people, but what do you really know about them?”

The fact that we even have theater in our community is a privilege, White suggests, a cultural expression of a society that is stable enough to make it.

“The reality is, there’s more important things to focus on,” White says. “It’s kind of forgetting that there’s bad things in the world.”