Oregon has long had the goal of reducing carbon emissions, and in 2011, an Oregon Administrative Rule declared that by 2020, we should emit 10 percent less than we did in 1990. That milestone is right around the corner, and state legislators and climate activists are legitimately concerned that we are not going to make it.

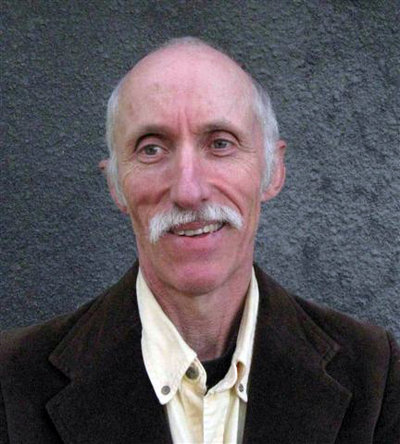

Tom Bowerman is a climate activist and program director for Eugene-based research center PolicyInteractive, and he has authored a bill called the “Climate Stability and Justice Act of Oregon” that would give teeth to the already stated emissions goals by creating legally binding, regulatory mechanisms.

The bill would authorize state agencies — the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and the Environmental Quality Commission (EQC) — to monitor and regulate greenhouse gas emissions. They would set targeted emissions limitations, in stages, for the next 35 years. They could also set up a system for greenhouse gas “exchanges” or “credits.”

Bowerman’s bill has not officially been filed in the Legislature yet, but Rep. Phil Barnhart will sponsor it. Barnhart has already introduced and co-sponsored several other bills to fight climate change. Barnhart says his goal, broadly, is to begin the process of transforming the state economy from one based on fossil fuels to one based on renewable energy systems. At this point, the two solutions he thinks might have traction in the upcoming legislative session are a cap and trade bill, like Bowerman’s, or a carbon tax.

According to Bowerman, who is also known by many as the son of track coach Bill Bowerman and grandson of former Oregon governor Jay Bowerman, he wrote his bill the way he did because of his research with PolicyInteractive and the Oregon Values and Beliefs Survey it conducted. “The public isn’t favorable to taxing carbon,” he says. But, it does favor putting a cap on carbon emissions, and then reducing that cap over time.

Bowerman argues that we need to align our social behavior with our understanding of the world we live in. He says the physical science is saying, “Boy, we better get our act together,” and the social science is a good 20 years behind.

In 2006, California passed a bill very similar to what Bowerman and Barnhart hope to accomplish. Assembly Bill 32 requires that the state reduce its emission levels to, at least, 1990 emission levels in 2020, and at most, the maximum technologically feasible level. California’s legislation is largely lauded as successful, so much so that Bowerman proudly says that he modeled his bill after Oregon’s southern neighbor. He says Oregon should “hitch our wagon to their economic model.”

Barnhart also has his sights set on joining California’s ride away from fossil fuels, and copying what’s working for them. “Instead of having to invent a new wheel, why not just use one that’s already working?” he asks.

California’s original bill did not say much about how the reduction would happen, or even who exactly would implement the regulations. That seemingly vague aspect is actually important and helpful, according to Bowerman. He says Oregon’s system works best if bills give leeway to administrative boards, so they can take the time to work out how to implement new laws. He’s designated the DEQ and the EQC to be the state agencies in charge of regulating and recording carbon emissions, but that could change. In California, the state set up a whole new agency to ensure compliance with the new law.

With Democratic majorities in both the House and the Senate, Barnhart is confident that something is going to happen this session on climate change. He’s not on the Energy and Environment Committee, where most environmental bills are initially referred, but he has faith in his colleagues that are on it.

“I’m very optimistic about Oregon’s future with a clean energy system,” Barnhart says. He thinks a few Republicans will stand with Democrats to initiate a transition to a renewable energy economy. He hesitates to say which bills have the best future, because “you don’t know until you actually get into the nitty gritty of it.”

Sen. Doug Whitsett, a Republican from Klamath Falls, has already made it clear he intends to oppose any “draconian” greenhouse gas reduction legislation. In a recent press release, he argues that global “warming” ceased in 1999. He says the “scientific and political elite” use the fact that weather changes somewhere on the planet every day to further fabricate their doomsday scenarios that necessitate a reduction in using fossil fuels. Whitsett says he is concerned that regulating carbon emissions will hurt those already struggling to pay their energy bills (California’s bill addressed this issue by establishing a “climate credits” fund). Finally, Whitsett says that since in Oregon, we represent .000057 percent of the global population, whatever we do won’t help in the global picture.

Bowerman says Whitsett’s concerns indicate that he has his head in the sand. Barnhart, maintaining his optimism, says that to pass a bill they “don’t have to convince everybody.”