Say the word “art” and most people imagine a painting — an original, unique work, done with oil paints on canvas, usually by an artist standing at an easel.

But it’s possible that more artists in Eugene produce fine-art prints than make easel paintings. Printmaking is flourishing here in Eugene and around the state. It’s hard to visit an art gallery in Oregon without seeing examples of contemporary printmakers’ work.

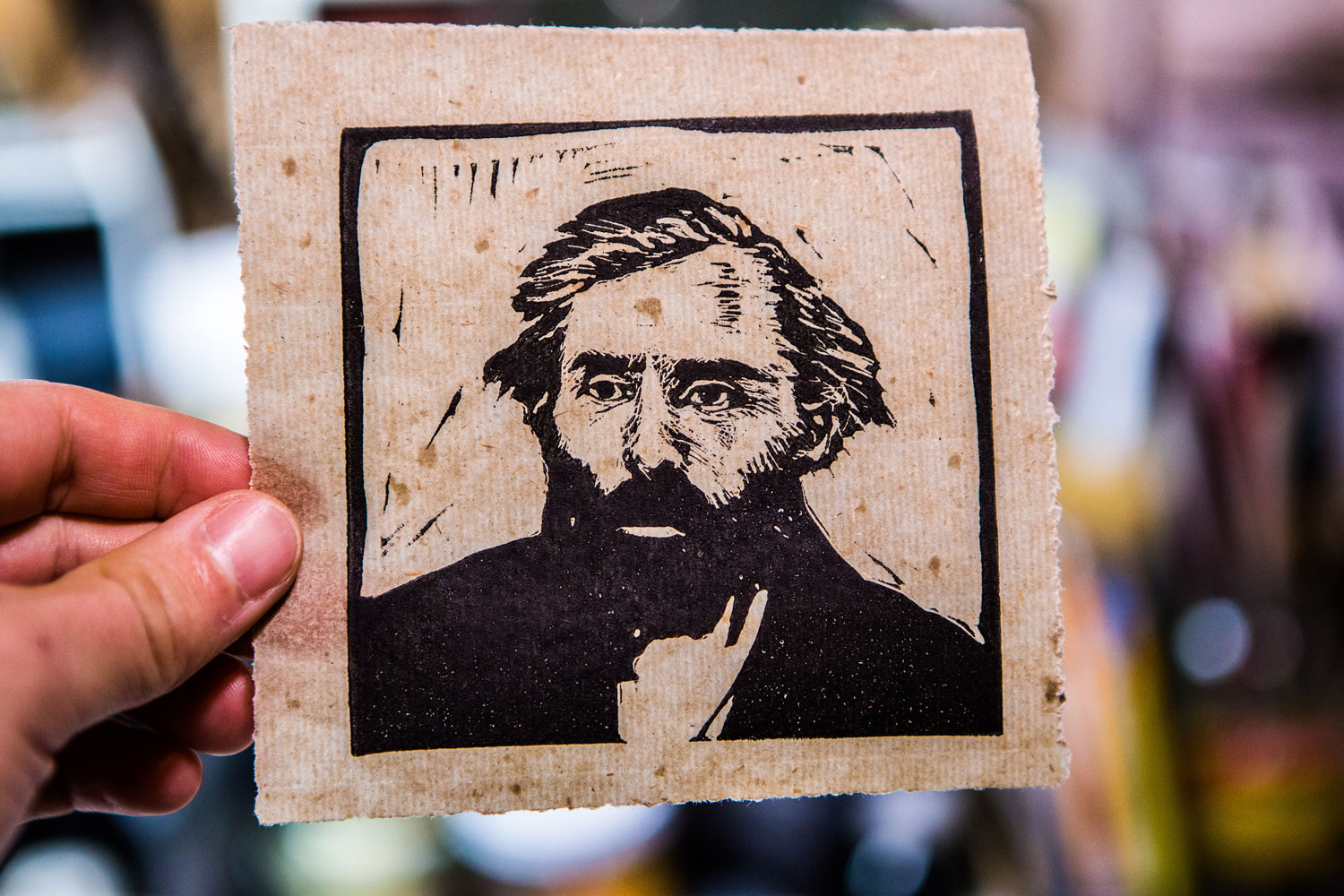

For the uninitiated, “printmaking” in the art world refers to making reproductions of images using traditional hand-crafted processes such as woodcut, etching or stone lithography, all of which require substantial hand work and artistic skill.

“There are so many people in the world of printmaking,” says Eugene printmaker Tallmadge Doyle, whose delicate, nature-inspired etchings have been shown here and around the world. “If you go to the Portland galleries you see a lot of prints.”

The Portland galleries that show the most prints are probably Augen and Froelick galleries, which happen to be next door to each other in the Pearl District.

Printmaking’s deep hold on Oregon goes back nearly a century. The godfather of printmaking here is Gordon Gilkey, an Oregon native born in Scio who received the very first master of fine arts degree awarded at the University of Oregon, in 1936. It was in printmaking.

Gilkey taught art at Albany College, now Lewis & Clark College, before going to New York to make 35 official architectural etchings for the New York World’s Fair of 1939.

With the arrival of World War II he joined the Army Air Corps, where his job was to identify landmarks in Europe that should be spared from Allied bombing.

At war’s end, Gilkey served as head of the War Department’s German War Art Program, sleuthing out and seizing troves of Nazi propaganda art, working in parallel with the more-famous Monuments Men, documented in a 2014 George Clooney movie of the same name, whose job was to locate and rescue historic artworks that had been looted by the Nazis in their sweep across Europe.

In the process Gilkey made friendships with international artists that would last the rest of his life.

When Gilkey came home to Oregon after the war, he became dean of the College of Liberal Arts at Oregon State College, was the first chair of the Oregon Arts Commission and later served as curator of prints and drawings at the Portland Art Museum, where he had donated his massive collection of prints and drawings, which eventually numbered 25,000.

Gilkey died in 2000.

“We’re in a room that’s named for Gordon Gilkey,” Anne Rose Kitagawa says, looking around a small study center inside the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art in Eugene. She’s the museum’s chief curator. “He casts a broad shadow over the rest of this institution, and in Portland, as well.”

The museum itself is named for arts patron Jordan Schnitzer, a Portland businessman who has amassed a large collection of contemporary American prints since he began collecting in 1988. His personal collection and that of the Schnitzer Family Foundation count, between them, more than 10,000 prints and other multiples.

The UO has its own collection of prints that have influenced artists here and elsewhere. The Schnitzer was originally built to house 3,700 pieces in the Murray Warner Collection of Oriental Art, which was donated to the university by Gertrude Bass Warner. Many of those were Asian prints.

The museum also houses a separate Asian print collection donated by the late Yoko McClain, whose husband was a printmaker and collector.

All that background may or may not have had an impact on the current state of printmaking in Eugene and around Oregon. Certainly most Northwest art is highly influenced by Asia, going back to the look of such Northwest School mystical painters as Guy Anderson, Mark Tobey, Kenneth Callahan and Morris Graves.

Enlarge

Photos by Todd Cooper

“I have also noticed an uptick in printmaking in recent years,” says Heather Halpern, a Eugene printmaker who, with her husband Paul, runs the nonprofit Whiteaker Printmakers studio, also known as WhitPrint, at 1328 W. 2nd Avenue. (WhitPrint is holding its annual holiday sale from 2 pm to 8 pm Friday, Dec. 8; 10 am to 8 pm Saturday, Dec. 9; and noon to 6 pm Sunday, Dec. 10; more info at WhitPrint.com.)

Halpern says some of the new interest in printmaking comes from the fact that it’s easy to see other artists’ work on the internet — but it also grows from a reaction to the soullessness of technology.

“In earlier times, I think fascination with printmaking came in waves with popular artists, instructors, and gallery shows,” she says. “The surge in traditional printmaking is also a reaction to being bombarded with technology. People take pleasure and pride in originality, creativity and rediscovering lost arts. Lots of young people are picking up knitting, canning and other activities that were largely abandoned when the industrial revolution no longer required individuals to possess such skills.”

Doyle agrees. “Despite all the digital technology, a lot of artists are doing these very traditional methods of art making. A hand-pulled print that has the hand of the artist visible — you’re never going to get that quality with digital. Digital has no soul.”

No one seems to be keeping track of how many printmakers are making art, whether here in Eugene or around the country. But Oregon has a number of substantial printmaking communities, including Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts in Pendleton, founded by Native artist James Lavadour 25 years ago to teach printmaking to Native artists.

Enlarge

Photo by Todd Cooper

An exhibit running through Dec. 22 at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Salem celebrates the work of Crow’s Shadow artists, who include such luminaries as Lillian Pitt, Wendy Red Star, Marie Watt and the late Rick Bartow.

“The print community in Eugene is incredibly strong,” says David Hilton, a long-time Eugene collector of fine art prints. His collection includes work by Rembrandt and Picasso as well as more contemporary artists.

Off the top of his head he names off Tallmadge Doyle, Susan Lowdermilk, Lynda Lanker, Margaret Prentice and Ken Paul as just a few of the artists producing work here. “They are all people who at one time or another were associated with printmaking at the UO,” he says.

And that, he says, comes back to Gilkey. “You can’t talk about Oregon printmaking without putting Gordon front and center.”

Prints, Hilton says, are “the people’s art form.” That goes back to late medieval Europe, when the invention of the printing press was the equivalent of today’s internet revolution.

Artists who were creating work only for wealthy patrons such as royalty and the church suddenly found a much broader audience when they were able to make multiple prints. And that, Hilton says, allowed artists to explore more personal themes in their work. “Artists could do work about what they’re seeing and experiencing day to day because they suddenly had a whole new venue to distribute their work.”

Enlarge

Photo by Todd Cooper

Similarly, he says, the rise of Modernism was driven by a multitude of printmakers. “They understood the mass market,” he says. “And Andy Warhol was the pre-eminent example of that. He saw the art in the everyday thing.”

Another democratization of art may be happening, at least locally, by way of printmaking.

Halpern, at WhitPrint, says printmaking here is led by women. Like most areas of art, printmaking was long dominated by men.

“I have encountered many more women than men in the field,” she says.

“Historically, the opposite was true. Even in the late ’80s, I was steered away from a college printmaking department full of chauvinistic men and intimidating equipment. Now, most of the printmaking studio directors I encounter are women, like myself.”

Enlarge

Photo by Todd Cooper

Halpern says she checked the member gallery on the website of Print Arts Northwest to verify her impression. She found 45 women and 13 men represented there.

“At WhitPrint, most of our members have also been women — about two to one.”

She suspects a number of reasons lie behind the change.

“Automated printmaking made certain jobs obsolete so men changed occupations,” she says. “Women got better access to facilities and instruction, women gained acceptance as artists, etc.”

Halpern herself got into printmaking in a roundabout way.

“I had been drawing, painting and sculpting since early childhood, but was discouraged from printmaking by then-respected instructors and peers,” she says.

Later one fall she was painting in encaustic — thick wax — and was looking for ways to incorporate images on transparent paper in layers in the wax.

“I experimented with block printing, but wanted more detail,” she says. That meant etching.

Etching wasn’t offered until spring term at Lane Community College so she took fall and winter classes in monotype, collagraph and relief printing. “By the time I completed my training in etching and aquatint, I was so enchanted with printmaking and the community it connected me with that I haven’t returned to encaustic painting. Yet.”

That was the beginning. What has kept her making prints is the charm of the slightly arcane process.

“Creating unique works of art is extremely satisfying. Most printmaking processes are time-consuming and absorbing, providing a beautiful respite from a stressful world,” she says. “For many, it’s a type of meditation.”