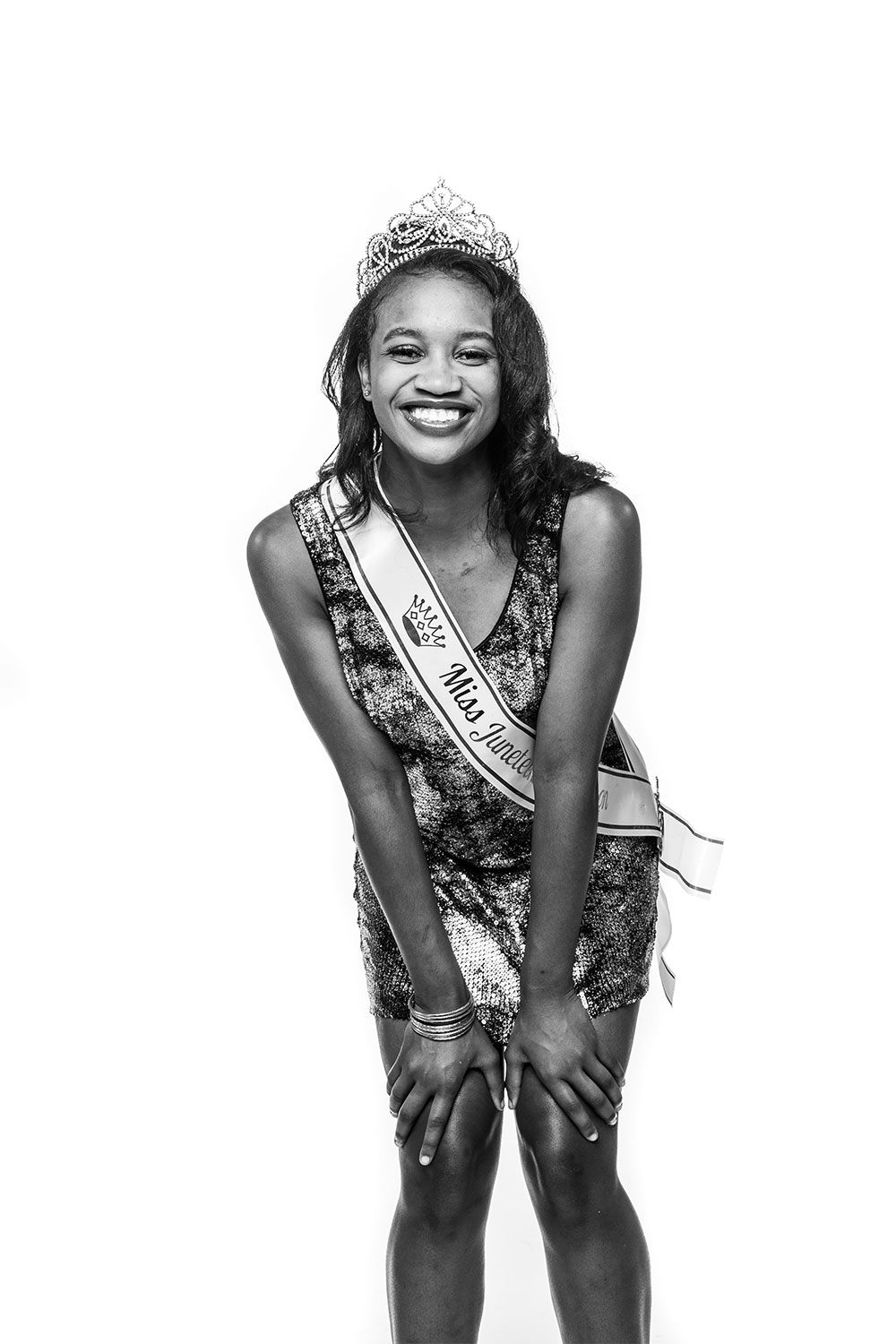

Aceia Spade is Oregon’s second Miss Juneteenth, and part of her mission in this largely white state is to educate people on Juneteenth, a holiday celebrating liberty and freedom from slavery that takes place two weeks before the U.S. celebrates the Fourth of July.

Juneteenth, or Juneteenth Independence Day, has its origins in Texas, when the Emancipation Proclamation was finally enforced in 1865, after the collapse of the Confederacy.

Aceia is 15 years old and a recent transplant to Eugene from Alabama, a Southern state where the June 19 celebration is more commonly recognized. Aceia, who also goes by Ace, says that she was excited to learn about Clara Peoples, the woman known as “the mother of Juneteenth” in Oregon.

Peoples moved to Oregon from Muskogee, Oklahoma, and, as the story goes, was surprised to discover Juneteenth, also called Emancipation Day or Freedom Day, was not celebrated here. She worked in the Kaiser Shipyards in Portland and, as she told The Oregonian in 2011, she asked her supervisor in 1945 if she could tell hundreds of fellow employees that June 19 was an important day.

She was given permission. Peoples made the announcement and went on to found Portland’s Juneteenth celebration.

After they lost their home in the 1948 Vanport flood, Peoples and her husband, Hayley, moved to northeast Portland, where she founded a food pantry that went on to become the nonprofit Community Care Association, according to a 2013 House concurrent resolution honoring Peoples for her contributions to the state.

Peoples would inform the community about Juneteenth, Aceia says, something Aceia herself intends to do. Though, she cautions, “You should also do your own research; there’s only so much I can tell you.”

Peoples herself died in 2015, but the annual Portland celebration continues as it has since 1945. This year it featured music, vendors, a raffle and the annual Clara Peoples Freedom Trail Parade, in addition to Miss Juneteenth.

Oregon’s Miss Juneteenth Pageant itself is new, says pageant organizer Octavia Chambers. She was a Miss Juneteenth in Texas, and when she came to Oregon she teamed up with the Portland Juneteenth Celebration to start a pageant here.

This is the contest’s second year, and it also featured Little Miss Juneteenth, 12-year-old Rina Tchivandja. The contest is open to girls 9 to 19, and, Chambers says, “It’s not about the dress or the right shade of lipstick but about building communities.”

The girls learn about resilience, self-esteem and positive life choices. “It’s more than just a pageant. It’s about safe spaces for Black and brown girls to thrive and feel beautiful,” Chambers says.

A Complicated History

Juneteenth celebrations have taken place all over the country. They carry on largely through oral tradition, but the holiday hasn’t gotten much recognition in Eugene — a white city in a white state.

In the 2010 U.S. Census, 2 percent of Oregon’s population was Black, a racist legacy of being the sole state whose constitution explicitly forbade Black people from working, owning property or even living within its borders when it was admitted to the Union in 1859.

It was illegal for Black people to move into Oregon until 1926.

According to research by James W. Loewen, author of Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, Eugene itself was most likely a sundown town — an all-white town with an unspoken rule or actual restriction saying Blacks were not welcome.

Portland, while also historically white, had a Black community, especially after World War II brought many African Americans in to work in the shipyards as Peoples did, which might explain why that city has a continuous Juneteenth tradition while Eugene does not.

The origin of Juneteenth traces back to Galveston, Texas. It recognizes June 19, 1865, when Major General Gordon Granger read “General Order No. 3,” declaring that all slaves were free — two-and-a-half years after President Abraham Lincoln’s Jan. 1, 1863 Emancipation Proclamation.

Enlarge

Photo by Todd Cooper

Juneteenth.com, a website dedicated to the holiday, its history and its worldwide celebration, says there are a number of explanations for the delay. In the end, with the surrender of General Robert E. Lee in April 1865 and the arrival of Granger and his regiment, emancipation at last came to the state.

Mark Harris, Lane Community College faculty member and Eugene Weekly columnist, looks at Juneteenth with skeptical eye. “It’s mostly a thing if you are from the South and if you ignore certain things about Black history,” he says.

He says that when Texas was part of Mexico in the early 1800s it was under a Black president and slaves were freed. Later, as a republic and then as part of the U.S., Texas re-instituted slavery.

Harris notes the irony.

“You’ve been freed since the Proclamation, and they didn’t tell you that you were freed till two years later,” he says of Juneteenth. “But you were already free from 30 years ago.”

But, he says, despite the layers of irony, he’ll take “any excuse to talk about Black history.”

While Eugene has not had an ongoing Juneteenth celebration, Eugene-Springfield NAACP President Eric Richardson points to the NAACP’s Memorial Day celebration. The annual event was started by the Lane Community College Black Student Union in 2011, and has been hosted by the Eugene-Springfield NAACP to recognize the link between the fight for liberty and the story of the African American community.

“The Black community is not monolithic,” Richardson says of not only celebrations of Juneteenth but of African American culture and history.

“As a national identity and a people, there are few things that bind African Americans together. There are Black churches and historically Black colleges,” Richardson says, but even those create smaller communities.

There are also national groups such as the NAACP and Urban League, but, he says, “there is no canon of Black experience.”

Richardson says, for one thing, “we need to do better in our educational system, not to whitewash it, so to speak.” He adds that “Black folks have kept up a traditional, rural holiday and kept it alive,” and not because the educational system has done anything to aid in that.

He points to the work of the Black Student Task Force at the University of Oregon as an example of changes slowly being made. As a result of their work, Dunn Hall on campus was de-named after the task force demanded they “change the names of all of the KKK-related buildings on campus.” The UO is also building a new Black Cultural Center.

The local NAACP has its offices in the Historic Mims House on High Street. The house was purchased in 1948 by C.B. and Annie Mims. The Mims were the first African Americans to own a home in Eugene, and Richardson says they came to Oregon from Texas and likely were familiar with Juneteenth.

And while Juneteenth and other key parts of African American history have been maintained in oral tradition, one thing the NAACP has done at the Mims House is set some African American history down in stone with markers and plaques commemorating the Mims and other key Black figures. Richardson points out that in Egypt and around the rest of Africa, Black people have been writing in stone since the time of the pyramids.

The Pageant

Asked by the pageant what she would do if she were president of the U.S., Aceia says she would improve schools and the lives of people in low-income neighborhoods.

One thing she would like to see the Miss Juneteenth pageant do is develop a boys’ pageant as well. She would like to see Black men get more positive attention.

“Being a Black man in the U.S. is, like, the scariest thing,” she says.

These are points that Richardson makes, too: “Folks yearn for positive images,” he says.

He adds that those who talk about the poor, the houseless and the jobless in terms of “the bottom line” are “an affront.” That is how slave owners — monsters who bought and sold people — thought of those they enslaved, he says: “Never more than the profit margin.”

But he says the current tense atmosphere in the U.S. has some hope. “It’s actually a reaction to great promise actually coming to fruition: multiculturalism, diversity, nonviolence, civility,” Richardson says. “All the things everyday people embrace and enjoy.”

And those who embrace racism are “fighting against natural progress.”

Pageant organizer Chambers says that, through her Miss Juneteenth title, Aceia and other participants can talk about “school and race and how that makes them feel,” along with getting mentoring and encouragement “through a culturally specific lens.”

Chambers says the girls get together on weekends for at least six weeks and that “Black and brown girls can come together and talk about things that might never surface.” As Miss Juneteenth, Aceia will do public speaking and community service.

Enlarge

Photo by Todd Cooper

Aceia brings up an experience she had at Churchill High School in Eugene where another student threw a glue stick at her in science class. She had spoken up when he grabbed it from the kit she and the only other African American student in the class were using.

When Aceia complained to the school, and asked for an apology, she was told she was over-exaggerating, she says.

“I don’t feel like I should have to, but if I have to I will,” she says of dealing with racist incidents and “little remarks” that get made.

Like Chambers, Aceia says Miss Juneteenth is something more than a mere pageant — it creates a sisterhood. Aceia says when people in school ask her “what is that?” she now has a “bigger voice” to talk about Juneteeth and African American history.

Oregon became the 18th state to recognize Juneteenth in 2001 through a legislative resolution by then-state Sen. Avel Louise Gordley, the first African American woman to be elected to Oregon’s state Senate. Hawaii, North Dakota, South Dakota and Montana have yet to recognize Juneteenth, and the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation has been trying for years to get Juneteenth recognized at a national level.

For more information on Oregon’s annual Juneteenth celebration, go to JuneteenthOr.com. For the pageant, check out MissJuneteenthOr.org and for more on the Eugene-Springfield NAACP go to NAACPLaneCounty.org.

This story has been updated.