One night while they were both on the art faculty at Lane Community College, Tom Blodgett and Craig Spilman literally came to blows. The two men laced up boxing gloves and went at it over some small matter neither one could, or would, later describe.

But Spilman is not one to hold a grudge.

“Regardless of my mixed feelings about Tom personally, I’m a tremendous admirer of his work,” says Spilman, who is the guest curator for the first Eugene show in years of work by Blodgett.

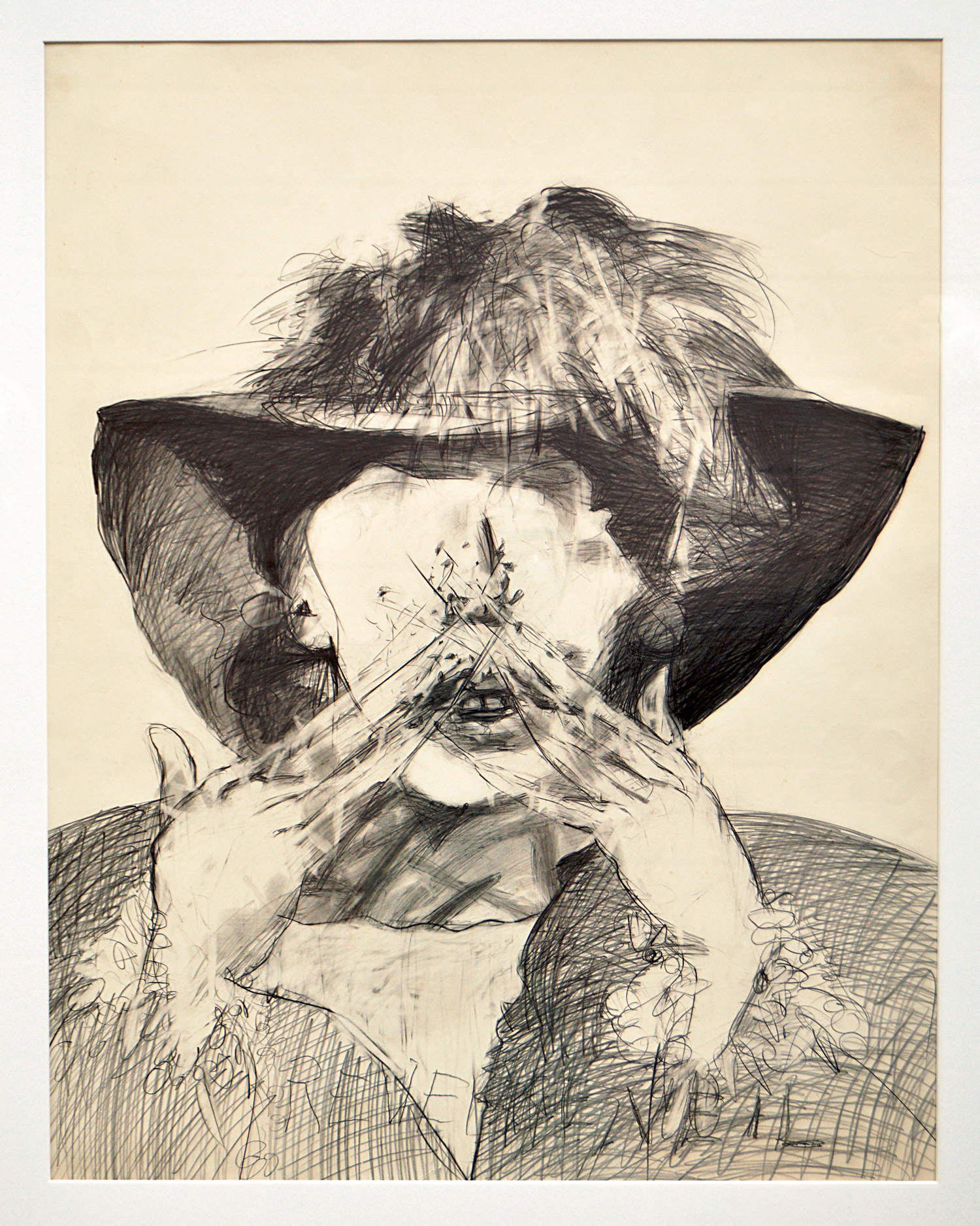

Faces, Figures and Phantoms: A Partial Self-Portrait opens Sept. 30 at the Karin Clarke Gallery. “He’s one of about three artists I can think of in my lifetime that actually did work powerful enough to bring me to tears,” Spilman says.

Blodgett, who died of cancer in 2012, was an archetypal eccentric genius. Any number of people who knew him will tell you he might actually be the most brilliant artist Eugene has ever produced, certainly the best at drawing. Unfortunately, Blodgett always told you that, too, forcefully and repeatedly, often in practically the same breath denigrating arts world people trying to help him.

“Americans don’t understand art,” he told me in a 1999 interview. “They believe illustration is art. In their mind art is just something in your head. An opinion!”

Blodgett often claimed no Oregon painter had a work in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. He boasted that he would become the first artist from our state to have work in that august collection. The basis for this, not surprisingly, turns out to be untrue, and wasn’t true when he said it: The Met, for example, has in its collection a 1949 painting by Clayton S. Price, who spent most of his career in Portland.

But Blodgett battled serious demons his entire life. By his own account, he suffered from obsessive behavior as a child. When he was 10 he stopped eating for long enough that he landed in the hospital.

In grade school, while other children were drawing pictures of fairy princesses or souped up hot rods, Blodgett was making pictures whose violent and sexual content disturbed his teachers, perhaps a harbinger of the dark, brooding pictures he would later make as a professional artist.

Blodgett studied art at Lewis and Clark College, where he graduated in 1962, and then got an MFA degree at the University of Oregon in 1966, working with such regional luminaries as David McCosh and Jack Wilkinson.

As an adult, his demons included alcohol, and Blodgett later admitted he had been a serious drunk until he dried out in the late 1980s. Drinking, he said, was such a foundation to his life that it took him months to learn to draw without a bottle by his side.

Despite his lofty aspirations and indisputable artistic skills, Blodgett never made it to the art world’s big leagues. His drawings got one show in a New York gallery in 1977, but in general he was so demanding and difficult to deal with that he sabotaged any hope of a broader career.

Two decades ago, I interviewed Blodgett for a story in The Register-Guard. He was living in those days in a run-down house in south Eugene, a place with shaky plumbing, bad heat and a leaky roof. He was being supported by a cultish group of young art students who brought him groceries and cigarettes in exchange for the chance to be near a man they considered an artistic genius.

Thousands of his paintings and drawings were mildewing in the damp rooms as Blodgett explained to me that he had discovered the secret of art — a secret as arcane and as mystical as those once sought by the alchemists. “It’s not the kind of secret you could just hand to somebody,” he told me, lounging on a dingy sofa and smoking cigarette after cigarette. “I know, now, how the Old Masters made those drawings. You’d have to spend a lot of time doing this, building up a visual literacy. It’s the kind of secret that requires pure ability. You don’t need to think about images or anything. That will come. It’s the weave, the weave of the universe. That’s what this is all about.”

Then he leaned toward me.

“I could kill you right now and nothing would ever happen to me,” he said. “It would just be called a psychotic episode.”

Set aside the man for the moment and look at his art. Blodgett’s drawings are exquisite — finely observed, deftly captured, perfectly expressive, without a trace of doubt or hesitation in his hand. He was as confident with a pencil or charcoal stick as Picasso. He drew people, primarily, with a dark energy that brings to mind a range of artists from Francisco Goya to Ralph Steadman. The faces in those drawings are haunting, with a surreal energy that can be disorienting. And Blodgett drew constantly, working through the day and late into the night.

“He got more content from a scribble than any other artist I’ve known,” Spilman says. “His almost palpable intensity when he was drawing gave his drawing an aspect of strength.”

Blodgett’s art has also drawn interest from a New York art consultant named Peter Hastings Falk, who specializes in bringing attention to little-known and undervalued artist estates.

In a lengthy essay on Blodgett, Falk compares his work to that of the Northwest visionaries such as Morris Graves, Mark Tobey and Kenneth Callahan, who were written about in a lengthy 1953 article titled “Mystic Painters of the Northwest” in Life magazine. “Spiritually he was more aligned with the mysticism of Mondrian, Munch and Kandinsky — whose paths to the unconscious influenced Marsden Hartley, Gordon Onslow-Ford and Jackson Pollock,” Falk writes.

After I met him in 1999, Blodgett — with no income to speak of — faced losing his home for non-payment of taxes. As luck would have it, he was saved by a woman he had married, divorced, remarried and later split up with but never legally divorced the second time. She died and, as her husband, he inherited $800,000. He used the money to pay his taxes, to remodel the house and to build a studio.

The Eugene show will include two dozen framed pieces and about 30 more pen and ink works that will be matted and sleeved, but not framed.

Spilman chose the work from hundreds of pieces now owned by Anne Fuller, a neighbor who befriended Blodgett when he lived in that squalid house in south Eugene. Though she has no art background, Blodgett left much of his artistic estate to her when he died in 2012.

Fuller has taken on the task of conserving Blodgett’s art in the hopes that it might finally be seen by a larger audience. She has catalogued and photographed some 4,500 drawings and paintings, which are now housed in the studio Blodgett built where that run-down house once stood.

Spilman says he and Clarke have discussed the idea of a Blodgett show on and off over the years, perhaps as a step toward helping the collection find a home at a museum. They finally started working to put together this show about six months ago.

“My hope was that Tom’s work would be something that would go into a place like the Schnitz [the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon] or the Hallie Ford [Museum of Art in Salem] or something of that nature,” he says. “But we’re going to start out small, right?”

Tom Blodgett: Faces, Figures and Phantoms: A Partial Self-Portrait opens Sept. 30 and runs through Oct. 31 at Karin Clarke Gallery, 760 Willamette Street. Hours are noon to 5:30 pm Wednesday through Friday and 10 am to 4 pm Saturday. Masks and social distancing required. Craig Spilman will give a curator’s talk on Facebook Live at 11 am Oct. 2; see Facebook.com/KarinClarkeGallery. See more about Tom Blodgett and his work at BlodgettCollection.com.