By Jack Forrest, Sally Segar and Jassy McKinley

Kathleen Escobar will never forget the day in November 2020 when COVID-19 hit the memory care center where her mother lived.

An aide from Table Rock Memory Care in Medford called to tell Escobar three of the facility’s residents had COVID infections. The aide reassured her: Escobar’s 88-year-old mother, Peggy James, showed no signs of having COVID.

But the news alarmed Escobar. She lived a few minutes away — she could dash over and bring her mother home until the COVID outbreak at Table Rock ended. The Table Rock aide told her that wouldn’t be necessary. The residents with COVID had been isolated. Her mother was safe.

“They acted like it was no big deal,” Escobar says. “They were very much like, ‘It’s all right. Don’t worry about it.’”

It wasn’t all right. Table Rock failed to contain the outbreak, and within days, the number of cases exploded from a few to 87.

Three days after telling Escobar there was nothing to worry about, Table Rock called back to report her mother now had COVID. “My mother suffered terribly,” Escobar says. “She had no idea what was happening to her.” On Dec. 3, 2020, Peggy James died from pneumonia brought on by COVID.

Eventually, 19 people died in the COVID outbreak at Table Rock. Escobar says she still struggles with anger toward Table Rock for failing to protect its residents and guilt that she didn’t rescue her mother when she had the chance.

“I think about it all the time,” she says now. “It was the worst mistake I ever made in my life.”

Across Oregon, families such as the Escobars watch helplessly as their loved ones suffer and die from COVID infections raging through the care facilities where they lived.

COVID-19 has proven especially cruel for America’s elderly who live in long-term care centers. These facilities include nursing homes, assisted living centers and residential care facilities. In all cases, residents live in close quarters and are served by staff who can spread disease from one room to the next. COVID’s swift and ferocious attack on those most vulnerable, such as the elderly, increases the danger.

More than 1,700 residents of Oregon’s long-term care centers have died from COVID-related illnesses, state records show. Those deaths are part of a national toll — COVID has killed more than 186,000 long-term care residents. The U.S. number doesn’t capture deaths in the past six months. But throughout the pandemic, outbreaks in long-term care centers account for one in every three COVID deaths.

News reports about high death counts in nursing homes and other care centers have made COVID outbreaks sound too common, familiar — even expected.

But these deaths were not inevitable.

Most care facilities followed strict protections against COVID-19 outbreaks. When followed, the rules worked and saved lives.

But other care facilities turned into death houses after their management ignored or broke COVID-19 safety rules. Regardless of the cause of the outbreaks, the state of Oregon’s Department of Human Services rushed in to help control the spread of COVID and ensure the care centers were following infection-control rules.

But Oregon has a double standard when it comes to holding accountable long-term care facilities that didn’t follow the rules.

Some long-term care facilities that allowed for deadly outbreaks paid a severe price for their lapses.

But far more walked away without any meaningful consequences.

How could that happen?

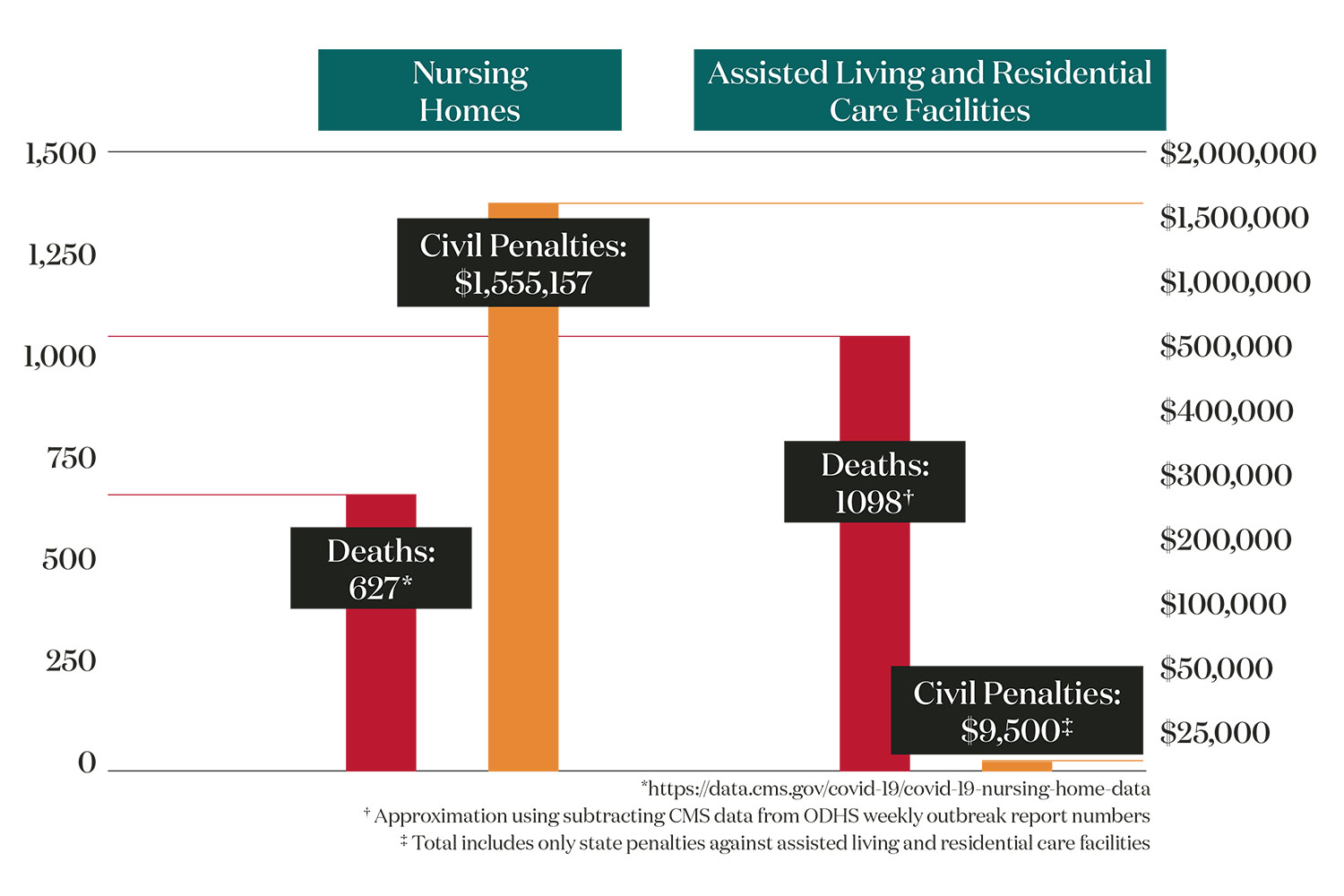

Oregon nursing homes, which operate under federal rules, have seen more than 625 COVID-related deaths. State officials, who enforce federal rules, have hit nursing homes with more than $1.5 million in civil penalties, records obtained by Eugene Weekly and the Catalyst Journalism Project show.

Federal rules let DHS fine rule-breaking facilities every day an issue goes unfixed, allowing those facilities to rack up fines in the tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars.

But time and again, Oregon DHS declined to issue civil penalties against long-term care facilities that play only under state rules. These facilities include assisted living and residential care centers. DHS officials early on decided they would avoid using civil penalties against these state-licensed care centers. The result: COVID outbreaks killed nearly 1,100 residents in these facilities.

The total civil penalties: A mere $9,500.

An investigation by EW and the Catalyst Journalism Project has found:

• Operating under the state’s rules, DHS has levied the $9,500 in civil penalties against 13 assisted living and residential care facilities that saw 50 deaths from COVID outbreaks since the start of the pandemic. Meanwhile, state officials have levied no fines against 56 other state-licensed care centers where major COVID outbreaks killed 463 Oregonians.

• DHS officials have failed to investigate care centers’ inability to control deadly outbreaks. In some cases, DHS officials failed to levy penalties even after inspectors witnessed care facilities ignoring COVID safety rules while an outbreak was killing residents. In the case of Table Rock, where 19 people died, investigators arrived to staff walking around without masks, among other violations. The state issued no civil penalty.

• Nearly 600 people died in care facilities that were facing a second or third COVID outbreak. At least 38 of Oregon’s 550 facilities saw a major outbreak bigger than the first. These outbreaks killed 317 residents. Not one of those facilities was fined.

• State rules require care facilities to alert DHS as soon as they identify a COVID outbreak — a requirement intended to curb the virus’ spread as quickly as possible. One Klamath Falls care center waited a week before reporting a COVID outbreak that was sweeping through its halls. In all 15 people died. DHS levied a $1,000 fine.

Top Oregon DHS officials declined to be interviewed for this story. Instead, the agency in a statement says DHS’s top priority was to move as quickly as possible to control outbreaks in care centers.

DHS spokeswoman Elisa Williams said in a prepared statement that reporting only on the tiny amount of civil penalties issued against state-licensed facilities is misleading. Doing so, she said, “implies that fines and penalties are the most effective preventive approach in protecting Oregonians and to save lives in a crisis situation when a long-term care facility experienced an outbreak. And, that they are the most financially punitive approach.”

But others say DHS’s failure to use its authority to hold facilities accountable after the fact underscores a tragic weakness.

While most long-term care residents in Oregon have been vaccinated, the Delta and Omicron variants have helped spark more cases. State records show dozens of outbreaks currently striking long-term care centers have already left 49 people dead.

Fred Steele, Oregon’s long-term care ombudsman, says the DHS and Oregon lawmakers need to reform state protections and enforcement powers.

“This is a systemic failure with the way our long-term care system has been structured to keep people safe,” says Steele, who serves as Oregon’s independent long-term care facility watchdog.

TRAINING DURING A CRISIS

Oregon has fared far better than most states when it came to controlling COVID-19 infections and limiting deaths from the virus. The state’s aggressive, early steps to halt public gatherings and require masks has kept the state’s overall COVID death rates among the nation’s lowest. Oregon has the 14th lowest per capita death rate in the country, according to Kaiser Family Foundation data.

These tough precautions translated to saving lives in care centers, too. Studies have shown that protecting the general population from COVID is the single-biggest factor in preventing infections and deaths in care centers.

But Paula Carder, the director of the Institute on Aging at Portland State University, says she feels Oregon’s regulations could have provided more details to guide assisted living and residential care operators during a pandemic.

“Although Oregon was one of a handful of states that mentioned epidemic or pandemic in their regulations, other states were more rigorous in their infection control policies,” Carder says.

Williams says nursing homes operate under federal rules that often require civil penalties for failing to meet reporting requirements. Federal penalties are far larger than those allowed by state rules. State rules require more evidence and it can take months to bring a civil penalty against an assisted living or residential care center.

Instead, she says DHS uses “license conditions” that prevent facilities from accepting new residents during the outbreaks. In extreme circumstances, DHS required facilities to hire compliance officers to oversee COVID safety plans. Williams says that many of these requirements were expensive and imposed something of a penalty on these care centers.

“Fines and penalties have significant limitations in a crisis response,” Williams says in a statement. “As outlined in Oregon statute and federal regulations, fines and penalties can be minor, take months for due process to play out and require diversion of significant resources during a crisis to both issue and defend.” Williams says there’s no state rule that allows DHS to levy a civil penalty simply because a facility had a COVID outbreak.

But the state has the authority to investigate and penalize facilities after the fact for COVID safety rule violations that contributed to the spread of an outbreak.

The licensing requirements Williams calls “punitive” nonetheless allow facilities to avoid the public embarrassment of a civil penalty, which creates a black mark on their public records. What’s more, DHS officials have frequently cited civil penalties as proof their agency is being tough on facilities — even as the agency in many cases avoided levying the penalties.

“The loss of life, as well as personal connections with loved ones, has been devastating,” Williams says in the statement. “We continue to grieve for all the lives lost and are committed to always working to improve our response as the challenges of the pandemic continue to evolve.”

But imposing expensive safety protocols is not the same as issuing civil penalties and formal sanctions that place a black mark on a facility’s permanent record.

Toby Edelman, a senior policy attorney for the Center for Medicare Advocacy, says too many states took the collaborative approach too far during the pandemic and failed to use their regulatory muscle when so many lives were at stake.

“Survey agencies were doing a lot more assisting and training and helping facilities,” Edelman says. “Which is basically not their responsibility to be teaching them and training them, they’re supposed to be regulatory agencies and enforcing the law.”

She says she fears state agencies will continue this conciliatory approach to rule-breaking care centers after the pandemic. “That’s alarming to me,” she says.

CAUGHT OFF GUARD

Americans saw just how swift and deadly COVID could be in care facilities in February 2020, when the Life Care Center nursing home in Kirkland, Washington, saw the first major care facility outbreak in the U.S. In the end, more than 37 of the facility’s 130 residents died. The facility racked up more than $600,000 in fines from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services after investigators found the facility failed to follow many infection-control and case-reporting guidelines.

The Kirkland case got international news media coverage, but its death toll has since been eclipsed by outbreaks in care centers around the U.S. that have killed 186,000 or more residents as of June 2021. More than a hundred facilities in the U.S. have had outbreaks that killed more residents than Kirkland’s.

One early outbreak that nearly matched Kirkland’s death toll was here in Oregon: Health Care at Foster Creek, a 114-bed nursing facility near Portland where 36 people died from a March 2020 outbreak. The state moved out residents and pulled Foster Creek’s license, effectively closing the facility in May 2020. The state found violations of federal rules and levied a $294,840 civil penalty — by far the biggest in Oregon during the pandemic.

But a July 2020 investigation by The Oregonian/OregonLive found the state’s response to this initial crisis was slow and chaotic. DHS regulators sat nine days on alarming reports that the facility was failing to adopt infection control guidelines needed to protect residents, the investigation found.

A report released in March 2021 by the Oregon Audits Division found Oregon officials had not been prepared for a pandemic — and that they should have been. The elderly in care facilities are always more at risk of infectious diseases. State officials had dealt with an H1N1 flu pandemic in 2009 and should have known another pandemic was inevitable.

“Despite the hundreds of norovirus and flu outbreaks that have occurred in the state’s long-term care facilities over recent years,” the report says, “Oregon appeared caught off-guard initially by how to respond to COVID-19 outbreaks in those facilities.”

The Foster Creek outbreak was still exploding, and state officials were still figuring out how to respond when warning signs flared at Marquis at Hope Village in Canby, a 166-resident facility that offers skilled nursing, assisted living and a memory care unit. In April 2020, a worker at Marquis at Hope Village reported witnessing violations of COVID protection rules to DHS. Employees were coming to work despite having COVID symptoms. Staff went in and out of resident rooms without face masks. And maskless workers ignored social-distancing guidelines.

The whistleblower, Erica Moreno, had already reported what she’d seen to Marquis at Hope Village’s management. The response: CDC COVID guidelines were “only recommendations” and that Moreno was “paranoid and overreacting,” according to a lawsuit Moreno later filed against the company.

DHS officials investigated Moreno’s claims, twice inspecting Marquis at Hope Village and finding no problem with infection control, according to public records obtained by EW and Catalyst.

Two months later, Marquis at Hope Village reported a COVID outbreak that led to 18 deaths and 113 infections, according to OHA data. The deaths climbed to 26 after Marquis at Hope Village saw another outbreak in November.

After the outbreaks, DHS officials reported they found deficiencies at Marquis at Hope Village. In one case, staff failed to screen state inspectors for COVID — even though employees knew DHS officials were there to investigate how well the facility was following rules.

Even as the death count grew at Marquis at Hope Village, DHS officials chose not to levy civil penalties. Instead, the state required the facility to show its employees YouTube videos of CDC-created slideshows on COVID.

Moreno’s lawyer, Christina Stephenson, says she sees the state’s response as lax, especially after her client’s warnings and the 26 deaths related to the Marquis at Hope Village outbreaks.

Residents “deserved the utmost protection by both the state and Marquis and that didn’t happen here,” Stephenson says. “If [Marquis] doesn’t suffer even the most basic consequences for their actions, then what is preventing them from doing it even worse?”

A HIDDEN OUTBREAK

Oregon defines an outbreak in long-term care facilities as three or more confirmed COVID cases or one or more COVID deaths. Those rules require that facilities immediately report outbreaks to health officials, allowing DHS to send in a team of surveyors who make sure the facility is doing all it can to make sure the outbreak is controlled.

But state officials can’t do any of these things if a care center conceals that it’s experiencing a COVID outbreak.

That’s what happened at Pelican Pointe Assisted Living & Memory Care in Klamath Falls.

On Dec. 29, 2020, records show, state officials discovered Pelican Pointe’s memory care unit had hidden a major outbreak with 21 cases for at least a week.

State officials arrived to find that, despite having an outbreak sweeping through the facility, Pelican Pointe residents were not wearing masks and staff were not wearing required goggles or face shields. Nor was Pelican Pointe screening visitors as required — the state inspector was allowed into the facility without being screened and had to ask staff to take their temperature.

It took more than two weeks before DHS took action against Pelican Pointe, declaring residents were in “immediate jeopardy” because of the outbreak.

By then, eight people at Pelican Pointe had already died and the number of infections had jumped to 47. And things only got worse. In all, the Pelican Pointe outbreak killed 15 people and infected 60.

Early action to stop an outbreak saves lives. Michael Wasserman, geriatrician and former president of the California Association of Long Term Care Medicine, says concealing an outbreak — and in effect refusing the state’s help to control the infections — is “reckless.”

“To have an outbreak and not to report it immediately — immediately — is just unfathomable to me,” Wasserman says. “What about the families? What about the other residents? How are you valuing the lives of the folks you’re supposed to be responsible for?”

Pelican Pointe is run by Frontier Management, based in Portland and Dallas, Texas, which manages more than 120 care centers in 19 states.

Andrea Fitzgerald, vice president of Frontier Management for southern Oregon operations, and other Frontier officials would not provide comment after repeated calls, texts and emails.

The state of Oregon had the chance to hold Pelican Pointe accountable for failing to report the outbreak.

So what did DHS officials do after 15 people died?

They levied a civil penalty for $1,000.

State officials declined to answer specifically as to why Pelican Pointe escaped with such a small penalty, given the severity of the violation and the consequences for its residents.

Steele, the state’s long-term care ombudsman, says the penalty falls far short of matching the severity of the violation.

“This is a building that is licensed by the state to provide care to older adults, vulnerable adults, people with disabilities,” Steele says. “And this facility chose to try to hide the situation. Is the $1,000 enough of a penalty? I would say no.”

LESSONS NOT LEARNED

More than 300 long-term care centers have seen multiple COVID outbreaks. Experts say repeated outbreaks alone are not a sign the facility is failing to follow guidelines. But second or third outbreaks that turn out to be deadlier than the first can indicate the facility failed to learn lessons, or the state regulators failed to enforce COVID safety standards. Perhaps both.

In Oregon, these second or third outbreaks often proved far more deadly than the first wave. Most of the major outbreaks in all Oregon care centers, when five or more people died, hit after the facility had already resolved a smaller outbreak.

Records reviewed by EW and Catalyst found 38 cases in which subsequent outbreaks at facilities turned out to be deadlier than the first and killed at least five people. Those repeat outbreaks led to at least 317 deaths.

Oregon DHS has not levied a single civil penalty against any of them.

Take the perplexing case of Gracelen Terrace, an 80-bed nursing facility in Portland.

Gracelen experienced an outbreak in July 2020 that caused 11 infections, according to state reports. During the outbreak, state inspectors found repeated deficiencies in following safety and infection control guidelines. The deficiencies included staff failing to provide residents with masks, keeping residents at safe distances in the dining hall, and failing to wash their hands after working with protective equipment.

No one died in that outbreak. But DHS officials issued a $12,870 penalty.

In September 2020, Gracelen convinced DHS officials it was in compliance with infection-control rules and reopened its doors to new residents.

Within three weeks, Gracelen Terrace had a second COVID outbreak, this one far worse than before. It rolled on for three months, killing 18 people and infecting 112.

Despite the deaths, the state has no plans to issue a civil penalty against Gracelen for the deadly second outbreak.

How is it possible that a facility gets a large fine for an outbreak in which no one dies, but no penalty for a subsequent outbreak that left 18 people dead?

DHS officials say they found no violations in the second outbreak — a claim experts find incredible.

Steele says the first outbreak shows that the infection-control measures worked, even though the state hit Gracelen with a major civil penalty. He says the 18 deaths in the second outbreak shows the system failed.

“Protocols were known to keep them safe, and that didn’t happen,” Steele says. “Quite simply it makes me angry.”

Wasserman agrees. “When you see the state came in, cited folks, walked away, then [the facility] had another big outbreak again,” he says, “that calls me to question the effectiveness of our approach to oversight. And I think that’s a huge question that we need to address.”

State corporation records show Gracelen is owned by H&L Care Centers Inc., based in Portland. EW reached out to Gracelen Terrace officials more than 10 times via email and phone with no response.

EW also asked H&L President Linda Pickering for comment over email and phone several times but did not receive a response.

ROCK BOTTOM

This disconnect between the death toll and the lack of consequences for facilities shows up most often with Oregon memory care centers.

A memory care center can be any type of facility that has additional security and safety measures for residents with dementia. They can pose additional challenges to prevent the spread of disease — residents often wander, making social distancing difficult, and they need to be reminded to wear masks.

The Oregon Audits Division report from March found that Oregon’s memory care centers were seeing twice the number of deaths per 100,000 residents The audit report noted the challenges for these facilities, but also adds that “given that outbreaks are still occurring after nearly a year of educational efforts, more proactive actions, including financial penalties, may be necessary to ensure that facilities are complying with infection control protocols.”

Perhaps the clearest example — and one of the deadliest — is the one at Table Rock Memory Care, the memory care facility in Medford where Kathleen Escobar’s mother, Peggy James, was infected.The initial report of Table Rock’s outbreak, cited in a Nov. 12, 2020, report from the Oregon Health Authority, listed eight inflections and no deaths.

State inspectors arrived to find repeated failures to protect residents. A heavily redacted Nov. 9, 2020, report released by the state to EW and Catalyst under the Oregon public records law shows state officials worried that Table Rock lacked the staff to handle the crisis. The report also shows the facility lacked adequate protective gear and sanitation protocols.

So many Table Rock residents and employees got sick that state inspectors refused to go back inside. Instead, state surveyors did reviews by phone. When they did go back inside on Nov. 23, 2020, state inspectors found continued problems with Table Rock’s infection control. While the outbreak continued, state inspectors witnessed a staff member without a mask emerge from an isolation unit and walk through the lobby.

In the end, the outbreak infected 113 people and killed 19, including Peggy James, Escobar’s mother.

Table Rock is owned and operated by Frontier Management, the same for-profit company that owns Pelican Pointe. Frontier Management would not discuss Table Rock despite EW and Catalyst’s repeated requests.

For all the deaths — and Table Rock’s disregard for safety precautions witnessed by state inspectors — DHS neve rissued a civil penalty.

State officials say that, during the outbreak, they compelled Table Rock to hire an infection control consultant, change its executive leadership and increase staffing. DHS officials claim they saw improvement in infection control, even as the outbreak grew to become the second most lethal in the state.

But DHS officials say they have no plans to hold Table Rock accountable for the violations that took place as the outbreak raged.

“It’s devastating to hear that 19 people died. What’s the accountability?” says Carder, the director of the Institute on Aging. “If you think of civil penalties and regulatory deficiencies as a way of having accountability, then where is it?”

This story was developed as part of the Catalyst Journalism Project at the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication. Catalyst brings together investigative reporting and solutions journalism to spark action and response to Oregon’s most perplexing issues. To learn more visit Journalism.UOregon.edu/Catalyst or follow the project on Twitter @UO_catalyst.