The U.S. entered the 13th year of conflict in Afghanistan Oct. 7, and the effort here sits on a knife’s edge. A week ago, the U.N. Security Council authorized the final extension of the international security mandate, which is now set to expire at the end of 2014. Ongoing deliberations between U.S. and Afghan governments will determine the future of our anti-terrorism efforts and training missions here after 2014. Coalition partners await the outcome of the U.S.-Afghan agreement to decide their own commitments. Negotiations with the Taliban continue in fits and starts. And on Oct. 6 Afghan presidential candidates registered for a democratic transition of power, a first in Afghan history.

Also on Oct. 6 four U.S. soldiers, including a 24-year-old from Philomath, were killed by an IED in Kandahar province, bringing the number of coalition forces killed to 3,390. The next day, reviewing the effort in Afghanistan, President Karzai declared that on the security front, “the entire NATO exercise was one that caused Afghanistan a lot of suffering, a lot of loss of life and no gains because the country is not secure.”

While Karzai’s comments may offend those who have sacrificed so much, at least he recognizes the challenges facing his country. Back in the U.S., where a bitter standoff that began with a senator reading from Green Eggs and Ham during a 21-hour call for a government shutdown that continues, it seems this war is forgotten.

Progress in Afghanistan is always difficult, but now it seems nearly impossible. In ideal circumstances, significant development requires steady effort, reliable engagement with Afghan leaders, continuous coordination with coalition partners, unending outreach, countless cups of Afghan chai and, in Herat where the coalition is Italian-led, many cappuccinos. The shutdown has pushed us much further from the ideal.

For instance, consider an ongoing development project that required travel to Kabul to meet with Afghan Minister of Water and Power Ismail Khan. Khan’s political career began as a junior officer in the communist government. Sent to Herat to suppress popular protests in March 1979, he instead ordered the Army’s weapons to be distributed to the crowds. They proceeded to storm city government buildings and executed a garrison of Soviet advisers and their families, putting severed heads on sticks that were then paraded through downtown Herat. The action marked the beginning of the Afghan war against the Russians and resulted in the eventual Russian carpet-bombing of Herat.

Khan led the resistance in the west for more than two decades, against the Russians then the Taliban. His political domination of western Afghanistan is near absolute, and his promotion to a cabinet position in Kabul failed to shake his position as its preeminent warlord. He is not a man to deal with lightly.

Flown to Kabul to brief Minister Khan on development projects in western Afghanistan, I cursed the government shutdown that left the project expert, a Defense Department civilian employee, behind in Herat because the $104 plane ticket could not be purchased.

After I had finished laying out our project in his Kabul office, a platter of grapes, pistachios and almonds alongside the requisite cup of tea in front of me, Khan inquired about the status of another construction project in Herat. I had to explain that although the project would be completed, while the U.S. government remained shut down, no money could be spent.

“This situation is difficult for those who support your projects, for the workers and those expecting them to be finished,” he replied through a translator. With a slight shake of his head, the cabinet minister of a nation that ranks near the bottom of every governance list asked, “How long until the U.S. is working again?”

Flying west after the meeting, the plane I was on aborted its descent into Herat International Airport and sharply climbed in altitude. As we circled over Herat, I looked out the plane’s window and noticed small explosions around Camp Arena, the coalition base near the airport. As we circled, I watched as insurgents lobbed mortars toward the people with whom I serve. Texting on my cell phone, I reported what I could see to the base operations center.

Fortunately, the plane eventually landed safely and no one was hurt. Thinking about the trip later, I realized that the airborne experience was less frustrating than sitting opposite Khan. At least in the air I could see what was going on and could report on the enemy firing at us. The government shutdown, more destructive on the whole than any indiscriminate fire from insurgents, leaves much of the American effort aimlessly circling, waiting for the conflict to subside, but blind to the details of the fight and impotent to counteract a force that fails to comprehend the damage being done.

Of course, the military is a fortunate part of the government — at least we still receive pay. My State Department colleagues living under mortar threat do not know if their paychecks will come. Military friends, injured by enemy fire, will likely not receive their veteran’s benefits. And in my mind, it is shameful to cash a paycheck while the government shuts down programs like Head Start or the Supplementary Nutrition Assistance Program for Women, Infants and Children. It is the antithesis of the Navy’s old-fashioned “women and children first” culture.

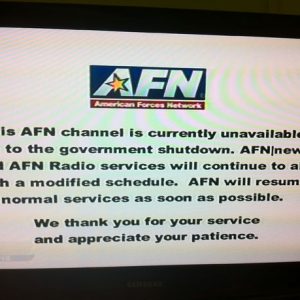

Perhaps worst of all, the shutdown even cut off the Armed Forces Network, a military rebroadcast of U.S. television. One cannot even seek out Oregon football to escape the frustrations of Central Asia.

In Afghanistan, as the presidential election gets under way, men (and some women) with antagonistic ethnic support bases, radically divergent national visions and often with violent histories (as well as command of large militias) are joining forces to form election tickets, each with one presidential and two vice presidential candidates. Though the election will certainly not solve all the nation’s problems, 27 tickets have been formed to seek a popular mandate to lead. Among those running is Khan as a vice presidential candidate.

If Ismail Khan, who oversaw a parade of his enemies’ heads through the streets, can accept the advantage of solving difference through building bridges with opponents and contesting policy differences through the normal electoral process, perhaps, with so much at stake and so much already sacrificed by so many, America’s leaders can as well. The effort here likely depends on it.