Gardeners! Maybe it’s time to take a fresh look at corn. We are not talking about sweet corn here, nor the notorious modern field corn that gives us corn syrup, ethanol and animal feed — and most of which is genetically modified.

We are talking traditional forms of field or grain corn, also known as maize, intended to be eaten as a staple food with minimal processing, that have sustained people of many cultures throughout history. If you’ve ever considered increasing your self-sufficiency by growing a grain crop, there are compelling reasons why you should consider growing suitable varieties of corn.

Carol Deppe, the Corvallis plant breeder and writer who has become well known in Eugene through her talks at home shows, claims corn is far easier to grow and thresh on a small scale than any other grain. It also has the highest yield of any crop other than potatoes. Besides, she says, growing and handling corn is “outrageous amounts of fun.” And Deppe can make a convincing case that corn may be better for you than you think.

While industrial hybrid corn, selected for high yield and uniformity, is relatively low in protein (about 9 percent), open-pollinated, traditional varieties like those Deppe grows may contain 12 percent protein or better, depending on variety. In any case, as she points out, unless you are eating only corn, protein content isn’t that important. The same goes for corn’s relative deficiency in available calcium and niacin, she argues: Just make sure you eat a variety of foods (including kale and beans!) and you shouldn’t have to worry.

There are three basic types of corn: flour, flint and dent. Flour corns have mostly soft, white, floury endosperm (the starchy part of the seed) that is easy to grind into flour that is good for baking. Flint corns, good for cornbread and polenta, have mostly very hard endosperm that may be white or yellow, and only a little floury endosperm. (Popcorn and sweet corn are forms of flint corn.) Dent corns have a more balanced combination. The outer seed coat of a corn kernel, called the pericarp, can be clear and colorless or colored red or brownish. Most of the colors you see in corn, and much of the flavor, are in the pericarp, but the coloring in yellow corn derives from yellow endosperm showing through a clear pericarp.

Corn likes heat. Grain corn varieties suitable for growing in the Northwest need to ripen and dry down early enough to escape the worst of the fall rains. This is especially true of flour corn. To make fine-grained bread, cakes, pancakes and gravy, Deppe uses Magic Manna, selected for flavor and cooking characteristics, “a very early flour corn I bred from Painted Mountain that shares its earliness, vigor and resilience.”

As for flint corn, “Abenaki is early enough to dry down in August here,” Deppe says. Abenaki (an eight-row flint also known as Roy’s Calais) has a mix of pale yellow and red cobs, and is one parent of her Cascade series, the early eight- to 12-row flint varieties she selected and now grows. The other parent was Byron, another early flint that “was delicious but had narrow, fragile cobs that made shelling difficult.” Byron contributed a new pericarp color, maple, and improved husk coverage.

From the progeny of this cross Deppe ultimately selected three varieties, each of a different color and for a different use. Cascade Creamcap makes great light-colored cornbread. Cascade Ruby-Gold has cobs of several colors that make breads and quick-cooking polenta of different colors and flavors. Now you can take advantage of Deppe’s patient work and expertise by purchasing seed corn for several of her selections.

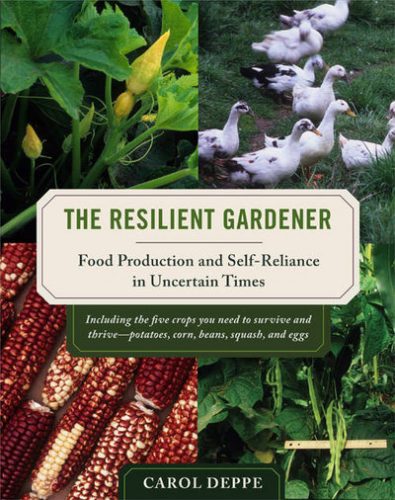

Deppe’s Cascade corns did well even on Vancouver Island, B.C., in the unusually cold summer of 2011. “If you grow an early grain corn like Abenaki or the Cascade series, you can also grow sweet corn with no cross pollination — they pollinate at different times,” Deppe says. To be safe, she adds, “use a late sweet corn variety and plant the Cascade corn two weeks earlier.” Cascade flints also tassel out too early to cross with GM feed corns. In her book The Resilient Gardener (Chelsea Green), Deppe has a lot more to say about growing corn, as well as how to plant corn to increase the likelihood of pollination. And how to optimize seed saving. And how to shuck and shell and eat corn. And about the relationship between kernel color and flavor in flint corn. And more.

To get Carol Deppe’s seed list, send an email to carol@resilientgardener.com. The list includes an order form you print out and return by snail mail. Deadline for orders is April 30 or when the seed runs out, whichever comes first.