Part II in a series on rape on campus and in the community

Weeks into interviewing University of Oregon administrators, police, professors and more, understanding where to go in order to report a sexual assault is still a maze of offices and administrators.

The school now has a hotline (346-SAFE) and a webpage that direct students to still more possible resources. But even if a student, traumatized after a sexual assault, figures out who to report to, there’s no guarantee that the bureaucracy at the UO will act, according to several professors who have been struggling to get the university to effectively prevent and deal with sexual assault.

The UO recently suspended the three basketball players involved in the sexual assault investigation, according to the victim’s attorney John Clune. The suspensions are for four years and could extend up to 10 years, he says, adding that his client is relieved at the decision. The 18-year-old woman intends to complete her degree at the UO.

UO spokeswoman Julie Brown confirmed Clune’s information and adds, “In all reports of any misconduct including sexual harassment, intimidation or violence, the university works to protect and support the students involved. Student safety is our top priority.”

UO professor Cheyney Ryan says, “I’m a white, male, distinguished professor; I’m not used to being ignored.” Yet Ryan, who is an emeritus professor teaching in the Conflict and Dispute Resolution Program at the UO School of Law, a senior fellow at Oxford University and a senior fellow of the Carnegie Council, says his concerns about sexual harassment and assault began in the 1990s and his attempts to get the UO to reform the way it deals with sexual assault began in earnest in 2009, but went unheard.

“Under federal law, you have to have a policy,” Ryan says. “If no one knows about it, that’s noncompliance.”

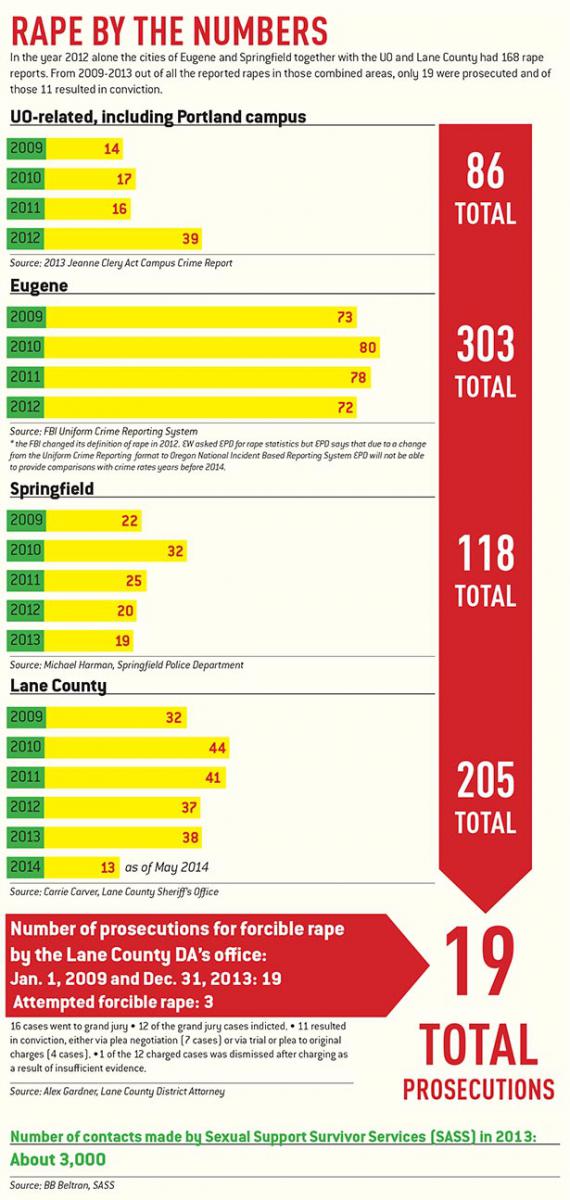

While rapes cases, like the one involving the basketball players, are dealt with by local law enforcement, they are also federal issues when they involve a public university. The Jeanne Clery Act mandates that campuses collect and report crime statistics and alert students. Title IX prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex against any person in education programs and activities receiving federal funding, and sexual violence falls under Title IX. A school that violates these laws is subject to losing federal funding and to stricter requirements.

Carole Stabile, the director of the Center for the Study of Women in Society at the UO, points out that she, like other university employees, is a mandatory reporter and must report if a student tells her she has been raped. UO mandatory reporters must tell their supervisor or the Office of Affirmative Action and Equal Opportunity.

“I believe in reporting. I don’t have a lot of faith in that system,” she says. She sends students to Sexual Assault Support Services, a local nonprofit that provides education, outreach, advocacy and support to survivors of rape. The UO did not sign its 2013-14 school year contract with SASS until after the basketball rape allegations had been reported.

Ryan echoes Stabile’s concerns and tells of several cases, some involving faculty members, where students were misinformed and reports went neglected by administrators. He says, “It’s always the same old story.” When students finally get heard by an administrator, they get “sympathy” but no action, he says. There is a tendency, Ryan says, for administrators to protect the institution.

Stabile and Ryan are among those who have tried to call attention to the UO’s institutional flaws in dealing with sexual assault. And because of their advocacy, they are also people that students seek out for help after they have been harassed or assaulted.

Stabile wrote a letter to UO President Michael Gottfredson in January 2013 telling him she had become increasingly concerned about the university’s handling of sexual assault and sexual harassment cases, and that she had observed a pattern “that suggests deep and serious procedural problems — problems that, if not addressed, will almost certainly erupt at some point.”

She told Gottfredson that senior administrators were “too close to the problems or too defensive about ‘the way we’ve always done things’ and lacked the critical perspective to deal with the problems.”

Stabile says she learned months later that on the same day she sent that letter, a student reported she had been drugged and raped by a UO fraternity member. She says she tries to talk about fraternities and athletics “in the same breath” as rape-supportive subcultures.

Ryan says when that student who had been sexually assaulted by a fraternity member tried to get help from the university, she had to tell her story to seven different people and still nothing happened. Ryan intervened, the student got an attorney and, he says, the university has offered her a settlement. “You get action if you go to a senior professor in law who knows someone,” he says. The student has asked that steps be taken so this won’t happen again.

The UO has appointed an eight-member external Review Panel on Sexual Misconduct Prevention and Response that includes former interim UO president Bob Berdahl, who is said to have been instrumental in hiring Gottfredson, Kevin Weiberg, who retired as the Pac-12 Conference’s deputy commissioner and chief operation officer, and retired judge David Schuman. The committee was appointed by Gottfredson, Vice President for Student Affairs Robin Holmes and Athletic Director Rob Mullens — who are also three of the people who have been widely criticized for the UO’s handling of sexual assaults.