Years before Opportunity Village came to life at the north end of Garfield Street, the idea of a transitional tiny house community was percolating in Andrew Heben’s head. While writing his senior thesis at the University of Cincinnati on the value of tent cities, Heben lived for a month at Camp Take Notice, a forested tent camp in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in which residents were involved in a complex process of self-governance.

“I saw these tent cities as an example of people developing a solution to their problem on their own outside of the reach of government,” Heben tells EW. “There’s this positive social dimension going on there that’s not happening in other responses, so I said, ‘How can we keep those positive social dynamics and improve the physical infrastructure?’”

Heben’s thesis became focused around the idea of efficient, social communities as a solution to homelessness. In 2011, Heben moved to Eugene just as the Occupy Eugene camp was being shut down, and by chance Jean Stacey, a local advocate for the homeless, read the thesis. Heben soon became one of the principal designers of a secure place for the homeless to settle, now known as Opportunity Village.

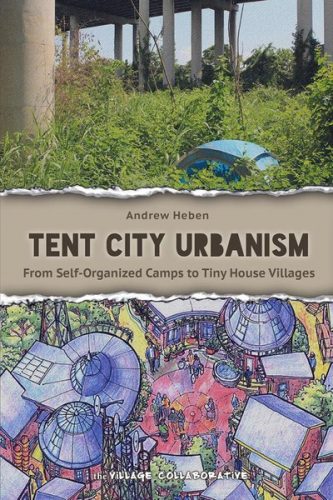

Heben overhauled his thesis to put his theoretical and observational research in context of his firsthand experience building Opportunity Village. The result is Tent City Urbanism, a self-published book in three parts: a conceptual framing of tent cities, detailed observations from tent settlements in seven cities around the U.S. and a guide to designing and building the social contract, facilities and homes of a successful tiny home village.

For those who have visited Opportunity Village, the guide section of the book is a fascinating look into how it operates so peacefully. It reveals, for instance, that its buildings are clustered in unorthodox ways as a “pattern language” to reflect the desires and needs of residents. It also includes the text of the Opportunity Village “Community Agreement,” the remarkable, open-minded document by which residents govern their community (including the following rule: “What I do will be based on love and respect for myself and others”).

The thing that might keep Tent City Urbanism from flying off the shelves is that it retains the precise language and structure of a thesis and places emphasis on the broad movement of communities rather than on individuals. But despite Heben’s intellectual voice, he is captivating in the theoretical first section of the book, arguing that tent cities provide a revolutionary new housing model for people at every income level.

“The residents of the self-organized camp are making decisions that directly impact their physical and social organization, and in doing so they are rediscovering key aspects of a sustainable community — most notably self-management, direct democracy, tolerance and resourceful strategies for living with less,” Heben writes.

Tiny home villages like Opportunity Village, Heben says, make evident the value of these ideas while letting go of the stigma associated with unauthorized tent communities. Heben argues that the broken window theory, which suggests that stopping petty crimes will in turn prevent more serious crimes (and has been a key argument in the eviction of homeless camps), may be flipped on its head.

“The kind of informal tent community that I am describing actually returns some quality of life to the population within,” Heben writes, “and by applying the same logic behind the broken windows positively, this benefits the surrounding population as well.”