fiction

The Slow Regard of Silent Things by Patrick Rothfuss. DAW Books, Inc., $18.95.

When an author says on page one, “You might not want to buy this book,” there’s a pretty good chance that what follows will not fit the parameters of an everyday novella. And that’s certainly the case with The Slow Regard of Silent Things, a pet project of fantasy writer Patrick Rothfuss. First of all, it’s difficult to understand if you haven’t read Rothfuss’ first two novels, The Name of the Wind and The Wise Man’s Fear — and as someone who’s read them, I have to say even that doesn’t help entirely. The 159-page novella takes a meandering, artsy glimpse into a week in the life of one of Rothfuss’ peripheral characters, Auri, a semi-insane former student of magic who lives underneath a mystical university.

The writing is unmistakably beautiful. Without using dialogue, Rothfuss sculpts Auri’s story with gleaming descriptions of her underground world, and his personification of the commonplace objects she anthropomorphizes and treats as equals is truly convincing: I never thought I could feel so closely connected to a metal gear. Auri is a fascinating character, and though the plot weaves and ducks with her erratic mind, it manages to crescendo at the end while hinting at the genius of her past, the lost potential of her present and the questions of her future. It’s not a normal read, by any means, but for those with a penchant for the unusual, this book fits the bill. — Amy Schneider

Silence Once Begun by Jesse Ball. Pantheon, $23.95.

Jesse Ball is a poet and none of his novels escape that fact. They are spaces you enter and moods you encounter more than guided tours through someone’s carefully crafted rendition of possibly realistic scenarios. They try to convince you they are important or entertaining for one reason or another.

He epitomizes the writer who loves language and romances its subtle, complex mechanism as a bridge between lived experience and the hard-to-pinpoint, wispy climbs where the lines between logic, meaning, fantasy and pure exploration are drawn and surpassed.

He is not grappling with the big questions as much as playing on the ground they spring from. He does not posture as one who provides answers to anything, but somehow culls an ancient sensibility that cuts to the heart of something vague, deeply human and unsettling in its spirit and contour; an element eerie, vast and subconscious in his writing.

Silence Once Begun is no exception, though its narrative path is more linear than his other novels. It is a story told through the journalistic fragments of a writer named Jesse Ball, trying to unravel a group of disappearances. I will omit any additional plot details, as they are ultimately irrelevant. — Paul Quillen

Written in My Own Heart’s Blood by Diana Gabaldon. Delacorte Press, $35.

The recent Starz miniseries bringing Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander series to sexy, kilt-wearing life has likely brought a horde of new readers to the tale of time-traveling Claire Beauchamp and her hot 1800s Highlander husband Jaimie Frasier. Written in My Own Heart’s Blood is the eighth official book in the series that has taken readers from Scotland, pre-the Battle of Culloden, to the American Revolution. The premise of the series sounds silly — a nurse is accidently swept 200 years back in time after encountering Stonehenge-like standing stones in Scotland, but Gabaldon’s vivid writing, with better-than-the-average-romance-novel love scenes and exquisite attention to the detail of life in the 1800s, makes it work. The Outlander books are a guilty pleasure that make you feel smarter for reading them. The weighty tomes are perfect for evenings curled up by the fire — just make sure you have whiskey at hand, because a taste for the hard stuff feels integral to the tales. — Camilla Mortensen

The Laughing Monsters by Denis Johnson. Farrar, Straus, Giroux, $25.

With the first sentence of Denis Johnson’s The Laughing Monsters, readers are deposited into the chaos that is the Freetown, Sierra Leone, airport — a place of sweltering heat where the PA system plays only the vowels. From there, within one short page, it’s a hustle through customs, scheming taxi drivers and then Freetown itself, “a mass of buildings, many of them crumbling, and all around them a multitude of shadows and muddy rags trudging God knows where, hunched forward over their empty bellies.”

Johnson, a master of economic prose, sustains this initial sense of dislocation and disorder throughout his new novel, which he self-described as a “literary thriller.” The Laughing Monsters follows Roland Nair, a rogue-ish intelligence officer who’s been sent to track down his old friend Michael Adriko, an African soldier of fortune who made loads of money with Nair 11 years earlier during Sierra Leone’s bloody civil war. Rogue-ish rather than rogue, because one of the threads of The Laughing Monsters is America’s sprawling, post-9/11 intelligence apparatus, which Johnson makes as wild and as tangled as the jungle mountains the book is titled after. As Nair says, “you realize it’s all myths and legends here, and lies, and rumors.”

Propelled by razor-sharp dialogue and the tension of never quite knowing who is screwing over whom until the very end, The Laughing Monsters is another masterwork from Johnson, who won the National Book Award in 2007 for his epic novel Tree of Smoke. — Eliot Treichel

Down in the River: A novel by Ryan Blacketter. Slant, $22. (Oregon author or Oregon-central book)

Set in Eugene, Down in the River is both a sympathetic depiction of bipolar disorder and a macabre take on youth culture. Now in Idaho, author Ryan Blacketter spent his teen years in Eugene, and the novel’s geography, from the river to the university, takes the reader through protagonist Lyle Rettew’s troubled existence.

Central to the book’s plot is when Lyle steals the corpse of a young girl from a mausoleum. Blacketter’s details are stark and somehow all the more disgusting for their sparseness. Yet Blacketter somehow maintains Lyle on his manic highs and lows as a sympathetic character. Adults in the novel, even Lyle’s 23-year-old brother who is trying to keep him on Lithium, are flat characters, paper dolls in comparison to the troubled youth on the streets of Eugene. The plot is disturbing, but you keep reading for Blacketter’s textured prose. — Camilla Mortensen

Women by Chloe Caldwell. SF/LD Books, $12.95.

Chloe Caldwell’s novella is about, go figure, women: specifically, about the aftermath of a breakup between two women, but also the friendships between women, both sexual and platonic, as well as the mother-daughter relationship. Caldwell does not shy away from exploring the intense bonds women form with each other — she wholly embraces them with stories of cringing familiarity.

Women, which is written in memoir style but is actually a work of fiction, is intimate and engaging from the first paragraph: The author explains that her pupils are expanding, which is either “a symptom of falling in love or a side effect of the Chinese herbs my transgender friend Nathan was hooking me up with.” Perhaps it’s the episodic structure and conversational tone that makes this 131-page novella easy to read in one sitting — or maybe it’s just that good. — Sophia June

The Spark and The Drive by Wayne Harrison. St. Martin’s Press, $25.99. (Oregon author or Oregon-central book)

If an auto shop on the East Coast in the 1980s seems an unlikely setting for a literary work of the highest caliber, think again. This debut novel by Wayne Harrison — an OSU writing professor and award-winning short story writer — is expertly rendered, a coming-of-age tale about a young upstart who falls under the spell of a brilliant mechanic only to fall in love with the man’s wife. Betrayal, desire and high drama ensue, all of it rendered in prose that is muscular yet poetic, and which mines its subject matter for deeper meanings and metaphors that hum like a well-tuned engine. Imagine Turgenev penning a story about first love among grease monkeys and gearheads, and you begin to grasp the heartbreaking story Harrison weaves, full of emotional depth and frank sexual longings that purr and hum until the whole engine of his novel combusts in the painful awakenings and hard knocks that always signal a coming-of-age. A moving book that is as much about love and loss as it is about mopars and mechanics. — Rick Levin

The Free: A Novel by Willy Vlautin. Harper Perennial, $14.99. (Oregon author or Oregon-central book)

Willy Vlautin, author of The Free, his fourth novel, is also a singer-songwriter with his alternative country band Richmond Fontaine, and his prose has the sometimes existential, sometimes quirky twang of Pacific Northwest alt country. The Free draws the reader through the intersecting tails of a brain-damaged Iraq veteran Leroy Kervin; Freddie McCall, who works two jobs and is still falling behind on his bills — he’s lost his wife and kids and his home is next; and nurse Pauline Hawkins, who aids the sick, including a troubled runaway and her mentally ill father.

Interwoven in the tale are Leroy’s dreams, influenced by the memories his damaged brain still holds and intermingled with the science fiction tales his mother reads at his bedside. The dreams become a metaphor for the damage humans do to one another, war crimes and baseless prejudice that resonate both for war and at home as echoes of Ferguson linger. — Camilla Mortensen

nonfiction

Astoria: John Jacob Astor and Thomas Jefferson’s Lost Pacific Empire: A Story of Wealth, Ambition, and Survival by Peter Stark. HarperCollins, $27.99. (Oregon author or Oregon-central book)

In a time when every inch of earth is spoken for or documented by Google Earth, it’s difficult to imagine that in 19th-century America — to rich, white men at least — the West Coast was just a hazy notion of somewhere beyond the territory of the recently acquired Louisiana Purchase and the insurmountable Rockies.

In Astoria, Peter Stark paints a beautifully detailed portrait of that time, picking up the tale of manifest destiny where Lewis and Clark left it. That hazy westward notion soon comes into focus for John Jacob Astor who, coming from surprisingly humble origins in Germany, went on to become a fur-trade tycoon and gained the trust of Thomas Jefferson to colonize and capitalize on the Pacific Northwest. As Stark writes, “Astor’s genius turned in part on his ability to look far beyond the obvious horizons of time and place and meld fragments of information on geography, politics, and trade potential into a much greater vision.”

To settle Astoria, Astor financed two teams — overland and seafaring parties — made up of a melting pot of pioneers from the ribald and flamboyantly dressed French-Canadian voyageurs (expert canoe paddlers for the fur trade) to Marie Dorion, a member of the Iowan tribe and the sole woman on the expedition.

While Astoria is initially a bit dry, it quickly delves into the colorful characters that faced the stark dangers of westward expansion and the unknown, elegantly nestling Oregon history into the grander scheme of the United States. — Alex V. Cipolle

Oregon State Penitentiary by Diane L. Goeres-Gardner and John Ritter. Arcadia Publishing, $21.99. (Oregon author or Oregon-central book)

If you’re looking for some light reading this winter, the new “Images of America” book Oregon State Penitentiary is neither light nor, exactly, reading. It is a fascinating visual history of the prison, taking the reader from its 1872 construction through the ’70s. The book starts dryly enough, with copious grainy black-and-white photos of the prison and its wings in the early 1900s. But soon the book’s narrative, carried by the plainly written photo captions, begins to reveal details about the prison’s history that are both heartening and disturbing.

It is perhaps not surprising that 100 years ago, most prison accommodations were dingy 9-by-5-foot cells that housed two inmates. It is less intuitive that in 1903, OSP started its first inmate-run publication, the monthly Lend a Hand. The authors even include an excerpt of a tragic poem published in the magazine, written by inmate Jack Catron. Its final stanzas read: “And all the words we vowed to speak, When life was young and dear, Died in silence, for they were Words no one wished to hear.”

Soon the book takes a much more sinister turn, culminating in the “Executions” chapter, which includes horrifying pictures of the prison’s gas chamber, which was used to execute 18 men from 1939 through 1962. Ultimately, the book affirms what we probably already knew to be true: The legacy of old prisons is dark and confirms the value of rehabilitation and restorative justice. — Ben Stone

Around Florence by Judy Fleagle. Arcadia Publishing, $21.99. (Oregon author or Oregon-central book)

Pick up Around Florence for the pictures, and if you’re a nerd like me who loves to know the history of any mound of earth currently beneath her feet, read the captions. The pages are filled with greats shots of the construction of the magnificent Art-Deco Siuslaw River Bridge and the Cape Creek Tunnel near Heceta Head, but unfortunately, Around Florence is a bit whitewashed. Fleagle only briefly mentions the first inhabitants of the area — the Siuslaw Tribe — choosing to focus more on Florence’s development after David Morse, the first white settler, arrived in 1876. — Alex V. Cipolle

Popular Skullture: The Skull Motif in Pulps, Paperbacks, and Comics Ed. Monte Beauchamp. Kitchen Sink Books, $19.99.

The idea is a deceptively simple one: an art book showcasing vintage illustrations of skulls. The surprising part is that, much like the skeletal system itself, that concept turns out to be quite flexible.

No bones about it, Popular Skullture provides precisely what it says it will: page after glorious, full-color page reproducing the covers of mystery magazines, paperback novels and comic books of the 1930s through the ’50s, each one prominently sporting an image of a skull.

Even the inclusion of the covers of novels authored by legitimate writers Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler and Ellery Queen can’t keep the distinct whiff of schlock off the project. From skull-visaged ghosts to skull-labeled bottles of poison to one unfortunate skeleton interred in a grandfather clock, Beauchamp’s entire lowbrow endeavor seems gleeful in curating its cabeza collection.

Popular Skullture demonstrates that, even at the height of the culturally sanitized 1950s, visual symbols of death and dying remained an intrinsic part of the zeitgeist. Consumed en masse, the 160 illustrations amount to an enthusiastic celebration of the lurid in the mind of mid-century America. — Aaron Ragan-Fore

Roadside Geology of Oregon, Second Edition by Marli B. Miller. Mountain Press Publishing Company, $26. (Oregon author or Oregon-central book)

Oregon has some spectacular geology, and for all the rock hounds out there, UO geologist Marli B. Miller’s newly updated Roadside Geology of Oregon provides everything you need to know about pulling over on road trips to gawk at feldspar and fossils. The first version of this guide came out in 1978, and a whole lot of awesome geology has taken place since then.

Miller’s book spans Oregon from coast to desert, filled with glossy pictures of Triassic-age limestone in the Wallowas and the lovely basalt columns that grace our very own Skinner Butte. Miller points out Oregon’s most recognizable geologic features (Crater Lake, for one), but she also hones in on lesser-known yet equally fascinating formations, like the absolutely gorgeous Rainbow Rock near Brookings.

The book is easy to follow, including a plethora of maps and detailed descriptions of how Oregon’s iconic landscapes came into being. For example: Oregon’s oldest exposed rocks are 400 million years old, found in central Oregon. And how cool is it that Mount Pisgah is made of “altered 30-million-year-old basaltic lavas”? If you agree, then bring this book along on your next road trip so you can enthrall (or annoy, if they’re spoilsports) your family with the age in millions of years of each passing rock formation. — Amy Schneider

biography

Leonard Cohen on Leonard Cohen: Interviews and Encounters (Musicians in Their Own Words) Ed. Jeff Burger, Chicago Review Press, $29.95.

Describing Leonard Cohen’s work, Brett Grainger writes, “His art can be read as the transcript of an extended interview with himself, a kind of spiritual journalism in which the poet addresses his attention to the confrontation with love and loss.” This certainly describes his art, but is also a literal description of this book of interviews.

It is a mixture of philosophical profundity, politely weaving through an Elmer’s glue, patty-cake minefield of un-thoughtful interview questions, and seemingly rehearsed, repeated refrains. The refrains are likely geared to survive being forced to iterate and reiterate answers to philosophical questions that are better voiced in lucid moments during intimate conversations with loved ones.

The grace of Leonard Cohen is revealed in his ability to remain engaging and intimate with people and a culture trounced by vapidity and addicted to avoiding the questions and concerns he is most enamored with; all done with compassion and genuine openness that stem from his acknowledgement that he himself is part of it and cannot escape it, as anyone else.

He is just one taking on the duty of reporting back to us from the shadowy corners. — Paul Quillen

autobiography/memoir

Yes Please by Amy Poehler. HarperCollins, $28.99. National Book Award Finalist.

The best part of Amy Poehler is she’s deliciously unapologetic about who she is. I first discovered this when reading her friend, and fellow comedian, Tina Fey’s book Bossypants: During a Saturday Night Live read-through, Fey writes, Poehler made an “unladylike” joke to which costar Jimmy Fallon responded “Stop that! It’s not cute! I don’t like it.” Poehler turned to Fallon and said, “I don’t fucking care if you like it,” and then continued on with her foul bit. To that I say hell yes and yes please.

In some ways, Yes Please is the sequel to Bossypants. With a loose structure reminiscent of a cool, flighty friend who doesn’t always stay on topic but keeps you laughing and interested, Yes Please is a call to arms for young women, or anyone who has ever been told they are “prettier in person,” to leave the world’s douchebags by the wayside and to go after what you want. Her vignettes on substances — Poehler was a major pothead — and pre-fame days in improv — the Upright Citizens Brigade — are expectedly hilarious, but there’s also a surprising depth and tenderness when she speaks about divorce and the eternal self-loathing demon we all have within us.

My favorite chapter (in a book full of chapters like “Humping Justin Timblerlake” and “Obligatory Drug Stories, or Lessons I Learned on Mushrooms”) is “Let’s Build A Park,” in which Poehler tells the origin story of Parks and Recreation and calls on the show’s creator Mike Schur to amend her memory of it with footnotes — a candid exercise that pulls back the curtain to reveal Poehler’s genius as well as her self-deprecating humility. — Alex V. Cipolle

Wild Within: How Rescuing Owls Inspired a Family by Melissa Hart. Lyons Press, $25.95. (Oregon author or Oregon-central book)

Any book with a fluffy owl on the cover is sure to get my attention. And local author Melissa Hart’s Wild Within is so much more than a love letter to birds of prey, although they certainly get ample attention. Hart’s memoir kicks off with a gloominess matched only by the dismal grey of an Oregon winter, which she describes with almost painful accuracy. Recently moved from California and separated from her lackluster husband, Hart tries to plant roots in Eugene but gets bogged down by muddiness and writer’s block.

When Hart meets handsome, pony-tailed Jonathan at the local dog park, things start looking up. Jonathan introduces her to the Cascades Raptor Center, and throughout the story, Hart works her way through the ranks, from cleaning up bird poop and leftover mouse guts to working with the birds themselves. And as Hart blossoms in her role as both partner and bird caretaker, she and Jonathan realize — shortly after Jonathan’s vasectomy, of course — that they want a member of their own species to care for.

Hart explores the heartbreaking, exhausting emotional roller coaster of adoption, offering a sobering glimpse into the reality of finding a child. Her writing is captivating, peppered with humor both dark and light, and the fact that it takes place in Eugene is an added joy to an already beautiful story. — Amy Schneider

A Fighting Chance by Elizabeth Warren. Metropolitan Books, $28.

When you turn the last page on Elizabeth Warren’s A Fighting Chance, you know you have heard from a master communicator. At first blush, this is an honest, forthright, unsophisticated story of a woman’s climb from poor Oklahoma to the U.S. Senate. But it’s not that easy. Warren has written nine books, taught at Harvard Law School, studied the complex corners of bankruptcy, built the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in the federal government and is now the constant subject of speculation for the U. S. presidency. She’s pretty sophisticated.

Her amazing ability to both communicate with and agonize for middle Americans trashed by the kings of finance has propelled her. One of the most telling lines in the book comes from her husband, fellow law professor Bruce Mann, after one of Warren’s tirades about Wall Street and the middle class. “What are you going to do about it?” he asked, and she was on her way.

When she campaigned in Eugene for Sen. Jeff Merkley, her energy and conviction came across in a rush unusual in American politics today. In her book, she plays dress-up with her grandchildren, shares her love for her Aunt Bee and other family members who helped her go through law school and into teaching while raising two children. Her love for the dogs in her life is a constant. But we finish A Fighting Chance wondering if Wall Street will allow Elizabeth Warren to go higher. Born in 1949, her age might limit her. This book has no insights into her knowledge of foreign policy. Whatever the next step, after reading this book, we know there will be one. — Anita Johnson

My Struggle: Book One by Karl Ove Knausgård. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $16.

Given the choice, would you agree to follow a complete stranger through the rambling pathways of his most intimate memories, as he recalls his life as thoroughly and fearlessly as possible, though not always in the most linear fashion? This might be a loaded question, but, in essence, Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgård is asking no less of his reader in his six-volume autobiographical novel My Struggle (Min Kamp in Norweigan, and yes, that title is controversial to say the least). The first book of Knausgård’s grand project — widely heralded as one of the towering literary achievements of this century — begins and ends, as do many great novels, with the specter of death. Namely, it is the death of the author’s father that so haunts him, as he and his brother spend hundreds of pages dealing with the aftermath of alcoholic demise, cleaning a grotesquely cluttered house full of decaying food and endless empty bottles.

Knausgård’s prose meanders along with the ebbs and flows of daily life, sometimes lingering for interminable passages on the everyday stuff of existence and occasionally bursting forth in stunning moments of revelation and reckoning. He flits back and forth through time, forever wrapping the present into the past and visa versa, and interspersing this with philosophical asides that distill experience into some sort of meaning, even in its apparent meaninglessness. Like Proust, Knausgård is obsessed with memory and the obsessive hold it has on us, the way every moment of our life accrues, often painfully, into this present moment. — Rick Levin

Not That Kind of Girl: A young woman tells you what she’s “learned” by Lena Dunham. Random House, $28.

Lena Dunham, even before her memoir, was a polarizing figure. With the 2012 debut of HBO show Girls, people either loved her — for candidly capturing at least a slice of the millennial zeitgeist, for her goofy narcissism, for her proud feminism — or they hated her — for that very candor, for her neuroses, for her privileged bohemian SoHo upbringing, for her early success or for her casual nudity. To that I said, “Down with the haters!”

But then the allegations came: Upon the release of Not That Kind of Girl, critics pointed to passages that Dunham wrote as evidence that she sexually abused her younger sister. Knowing that I’d be reading and reviewing this book, I didn’t want to have the same fangirl blind spot that many have for, say, Woody Allen. So I will say this: I’ve read the book, I’ve read the criticisms and then I read all the responses from sexual therapists, counselors and psychologists and their resounding answer is no, this is not sexual abuse, this is natural, albeit weird, adolescent exploration. The last thing I will say about that, because this book has a lot more to offer, is that Dunham may have fared better if she had composed these passages with less snark and more reflection.

Otherwise, Not That Kind of Girl is delightful. Here Dunham’s voice is original and strong, her writing more elegant and her insights into the female experience more poignant than on Girls. Dunham recounts her failures with glee and little vanity, exposing the worst of herself and others e.g., pondering unruly nipple hair while filming nude scenes, recounting her irresponsible relationship with prescription drugs or describing a breakup with a conservative college dude because of his “Phillip-Rothian” disdain for women. Dunham is ever the hilarious narcissist, but a softness and empathy does shine through, like when she writes, “My bed was a rest stop for the lonely, and I was the spinster innkeeper.”

If I could go back in time, I’d tell my 18-year-old self to read Not This Kind of Girl and not to worry so much. — Alex V. Cipolle

young adult

Forgive Me If I’ve Told You This Before by Karelia Stetz-Waters. Ooligan Press, $14.95. (Oregon author or Oregon-central book)

In 1992, Oregon voters rejected Measure 9, a ballot initiative that would have altered the state constitution and directed public schools to recognize homosexual behaviors as “abnormal, wrong, unnatural and perverse … and to be discouraged and avoided.” Measure 9 was primarily backed by the Oregon Citizens Alliance (OCA), a conservative Christian political group that previously fought to pass Measure 10, which would’ve required parental notification for any minor seeking an abortion. The campaigning around Measure 9 went beyond acrimony, as both sides became victims of harassment, vandalism and arson. Ultimately (and hells yeah), the initiative was defeated, 56.5 percent to 43.5 percent. Clinton was elected for the first time, too.

The fight against Measure 9 forms much of the background for Karelia Stetz-Waters’ debut YA novel Forgive Me If I’ve Told You This Before. Stetz-Waters grew up in Corvallis and now teaches writing at Linn-Benton Community College. Forgive Me follows Triinu Hoffman through four years of high school in “the grass seed capital of the world,” where she’s struggling to reconcile her Lutheran upbringing with her emerging sexuality.

While some of the book’s other characters feel one-dimensional, Triinu is rendered completely. Triinu is observant and funny, a real Oregonian, describing her disoriented self as a flounder whose eye has just begun to shift. Part of the real joy of this novel is watching Triinu find and accept herself.

“There’s no place to be brave anymore,” Triinu critiques, about midway through the book. “You just fill in the Scantron and wait for tomorrow.” By the end, however, inspired by friends new and old, she finds plenty of ways to be brave. — Eliot Treichel

Queen of Hearts Vol. One: The Crown, Vol. 2: The Wonder by Colleen Oakes. SparkPress, $15.

I’m a sucker for Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. As a teen, I memorized all of “Jabberwocky” as well as “The Walrus and the Carpenter.” Lewis Carroll’s work, like many older volumes we regard as children’s literature, is a wee bit disturbing, and its blend of childish fantasy and adult themes and humor can be like honey to a teenage fly.

Enter Colleen Oakes’ Queen of Hearts saga drawing us into a Wonderland with an apparently autistic (and gifted) Mad Hatter, who is beloved brother of Dinah, the future Queen of Hearts, a Cheshire Cat that is the scheming advisor to the king and massive “hornhooves” capable of galloping for miles through the forests and valleys of this fantasy world and then killing and eating their enemies. A little bit dystopian fantasy, a little bit twisted fairy tale, the Queen of Hearts saga pulls readers into its disturbingly evil kingdom of Wonderland. — Camilla Mortensen

A Sudden Light: A Novel by Garth Stein. Simon & Schuster, $26.95.

When I tell someone how much I enjoyed Garth Stein’s A Sudden Light, I do what most people do and try to summarize the plot. Plot summary will never get you an A in English class, and plot summary doesn’t do justice to Stein’s ability to capture the Pacific Northwest, its history and its ghosts, as seen through the eyes of a 14-year-old boy.

Trevor Riddell, the descendent of a Seattle timber family that has lost its fortune, returns to his ancestral home, a mansion made of giant old-growth trees with his father. Trevor’s mother, pondering divorce, stays away. At the mansion Trevor encounters his odd and sexually suggestive aunt Serena, ailing grandfather Samuel and the ghost of his dead, gay uncle Ben who, inspired by John Muir, wants to save the property of the North Estate from the logging and development that once built the family fortunes.

“You’re fond of owning the narrative, aren’t you?” Ben asks Trevor. Stein, author of the celebrated The Art of Racing in the Rain, also owns the narrative in the way he captures the big trees and giant characters of the Northwest in an engagingly woven plot. — Camilla Mortensen

poetry

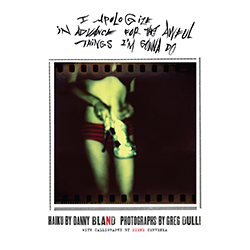

I Apologize in Advance for the Awful Things I’m Gonna Do by Danny Bland, photographs by Greg Dulli. Sub Pop, $14.95.

F. Scott Fitzgerald famously quipped that there are no second acts in American life, though author Danny Bland might disagree. Having done the ’90s thing in Seattle, playing music and, yes, getting himself into that scene’s more disastrous habits, he escaped the fate of many of his contemporaries, emerging as a sort of elder statesman and tour manager for such legendary acts as Dave Alvin. Bland also took up the pen, writing a novel (In Case We Die) and now a stunning collection of haiku poetry that delves — with a kind of brutalized tenderness and giggling gallows humor — into the shadowy byways of the male psyche.

Bland, who admits to knowing little more about haiku than its classic five-seven-five syllabic structure, nonetheless finds perfect expression for his familiar, blunt voice in the form’s strict economy. His poems are elegant graffiti painted on the walls of life’s lavatory, sometimes funny, sometimes sad, and they speak back to the reader with a burnt wisdom and beleaguered acceptance drawn from hard losses and, occasionally, the sudden flaring up of grace. One poem reads: “Everybody knows/ sideways for attention and/ long way for results,” while another, with a wicked wink, says, “I say tomato/ you say untreated, out of/ control sex addict.” Like Hubert Selby before him, Bland’s is the voice of the underdog, the survivor of addiction and purveyor of anonymous nights doing God-knows-what in seedy motels.

This is a bracing collection of verse, not for the faint of heart but oddly affirmative, even joyous in its embrace of downbeat humanity. It is gorgeously illustrated with photography by Afghan Whigs’ frontman Greg Dulli and calligraphy by Exene Cervenka of legendary punk band X. — Rick Levin