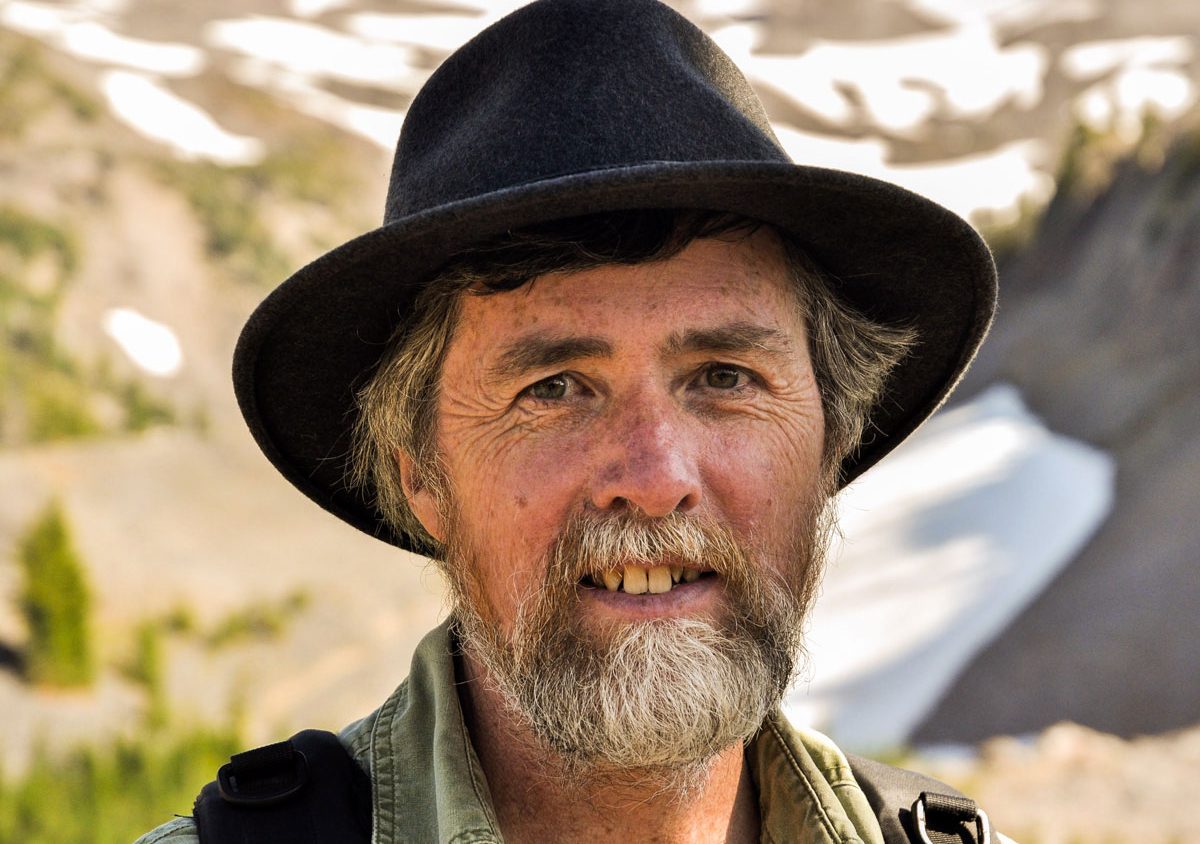

“Walking is the best physical exercise,” writer Bill Sullivan says. “People are designed to walk. It gets rid of the crap of civilization.”

Sullivan is pretty famous in these parts, and around the Northwest at large, for his collection of hiking guides. Many of us outdoorsy types have one, two or all of his books on our shelves.

On a cold December day, I caught up with Sullivan at the home he shares with his wife Janell Sorensen. The first thing that strikes a visitor — besides the resident turtle, Luigi — is the massive pipe organ in the living room. Before we settle in, Sullivan pumps out a rousing rendition of “Let It Snow.”

“I also play Bach fugues,” he says with a grin.

He shows me around his office, a repository of books and artifacts from a lifetime outdoors. And as any fan of his work would hope, Sullivan has a lot of hiking boots.

Then we take a walk.

Sullivan suggests a ramble through Eugene’s historic Pioneer Cemetery, and strides briskly out the door.

“To preserve Oregon, you have to know what’s there,” he says. “And you have to do it with your eyes open, not with your ear buds in.”

“What makes a top-10 hike?” I ask

“It has to be sturdy, so that you can send people there,” Sullivan says. “There are unexcavated sites in Oregon, endangered species, places I don’t want to send crowds.”

It’s through his books, he notes, that Sullivan disperses the pressure on our state’s natural environments.

“My books provide historical, geographical and geological interest,” he says. “If people understand more about the significance of where they are, they’ll be more proactive about preserving it.”

And walking, he explains, is democratic. “It doesn’t require any particular gear, except a pair of appropriate shoes and a backpack with the hiking safety essentials,” Sullivan says.

(Even casual day hikers should carry with them extra clothing, navigation aids, water, food, repair supplies, fire starter, first aid supplies, flashlight, sun protection and shelter, such as a “waterproof jacket or the like,” he says.)

In our community, many bus routes wind their way to trailheads. You don’t need a car to get to many of Lane County’s wild places.

But you need to know where to go and how to get there. “My books have been successful, I think, because I came at it as a writer,” Sullivan says.

Poetically scribed, with hand-drawn maps and clever details, these books have spurred generations of adventurers.

In addition to his hiking guides, Sullivan writes fiction, mysteries and short stories. His memoir, Listening to Coyote: A Walk Across Oregon’s Wilderness, was chosen by the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission as one of the 100 most significant books in Oregon history.

I ask him if he thinks up creative new writing ideas on his walks?

“Nope,” he says. “Walking burns off all the stress of the day, all the thinking. My best fiction ideas come to me in my sleep.”

As we’re passing through the fog, I ask Sullivan if he’s familiar with the Japanese concept of the “forest bath” — called shinrin-yoku — which involves visiting a forest for relaxation, recreation and stress management.

He looks at me patiently and says no, he’s not heard of that concept, although he understands the idea.

“Look at Outward Bound,” Sullivan says, referring to the experience-based outdoor leadership program. “You take kids who are messed up to the wilderness, and they get to get in touch with what really matters: Starting a fire, finding a flat spot, getting out of the rain.”

Nature as therapy?

“People were not designed to live in cities,” Sullivan says. “We were designed to walk in the woods.”