The traditional holy book of Islam has been defaced, burned, defecated on and denounced in the decade and a half that’s followed the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks by Islamic extremists on New York and Washington.

A new exhibition opening Friday and running through March 19 at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art presents a very different American reaction to the Qur’an.

In American Qur’an, the museum’s spacious main gallery will be full to bursting with the scores of original paintings that make up Los Angeles painter and lifelong surfer Sandow Birk’s reflection on the Qur’an.

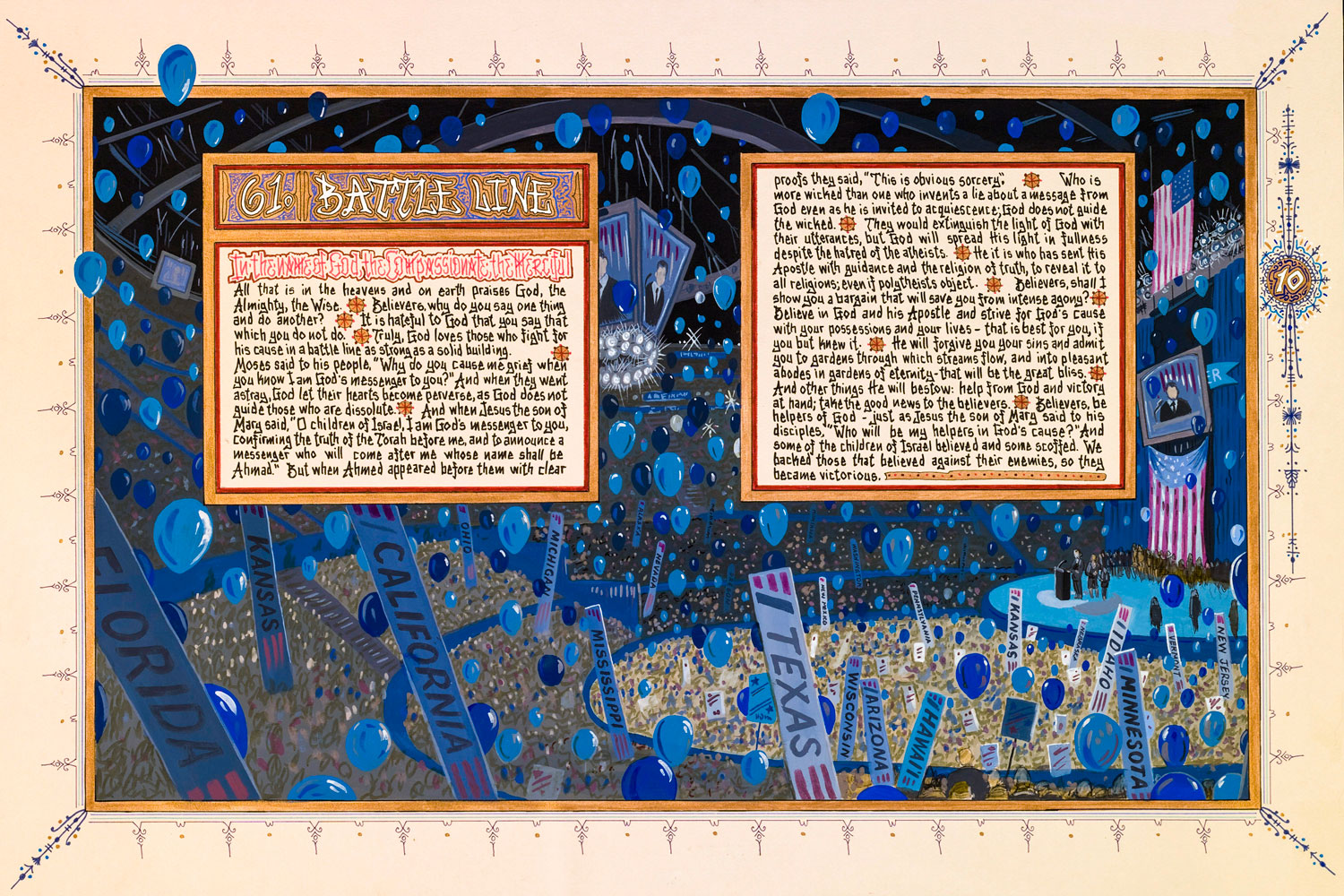

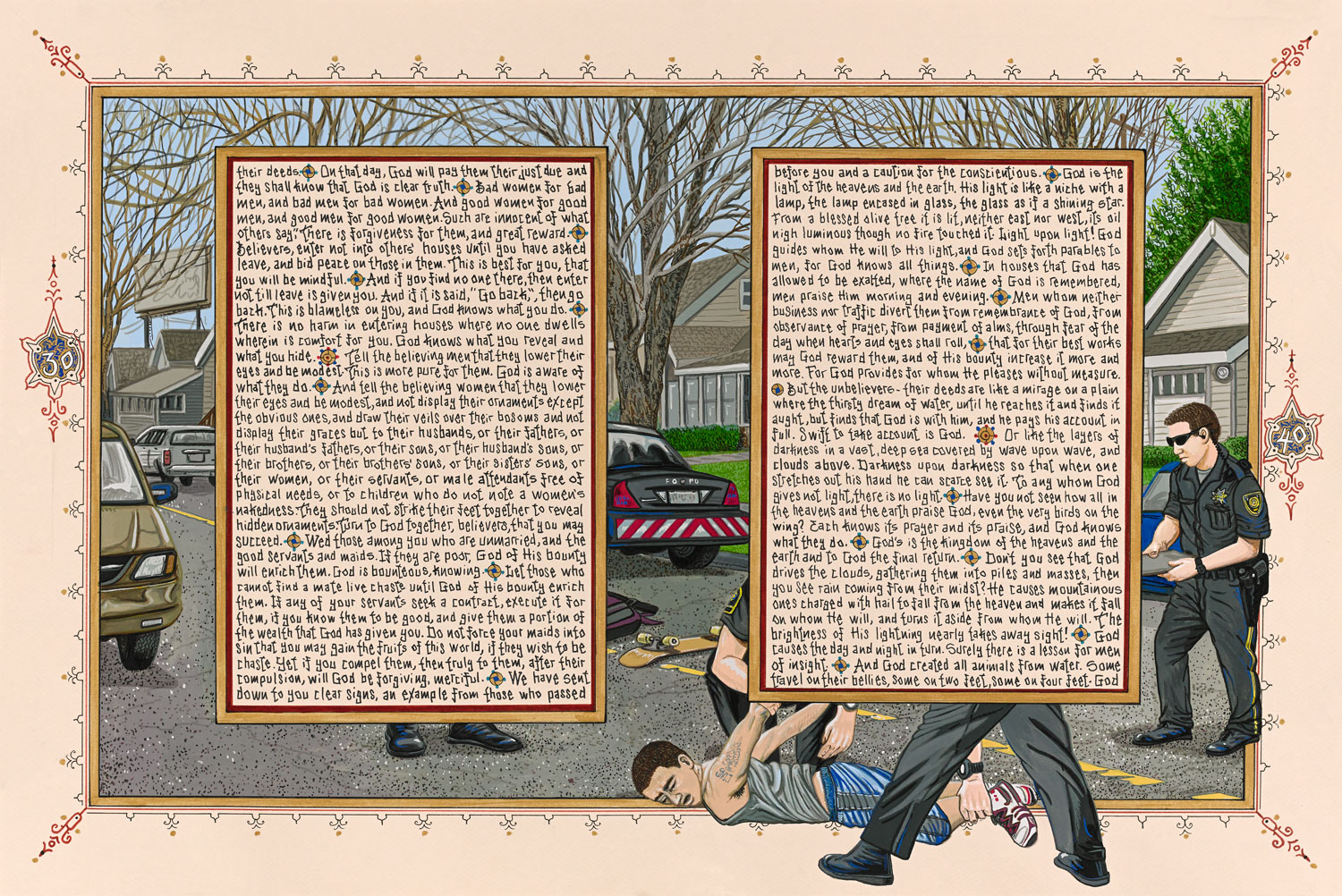

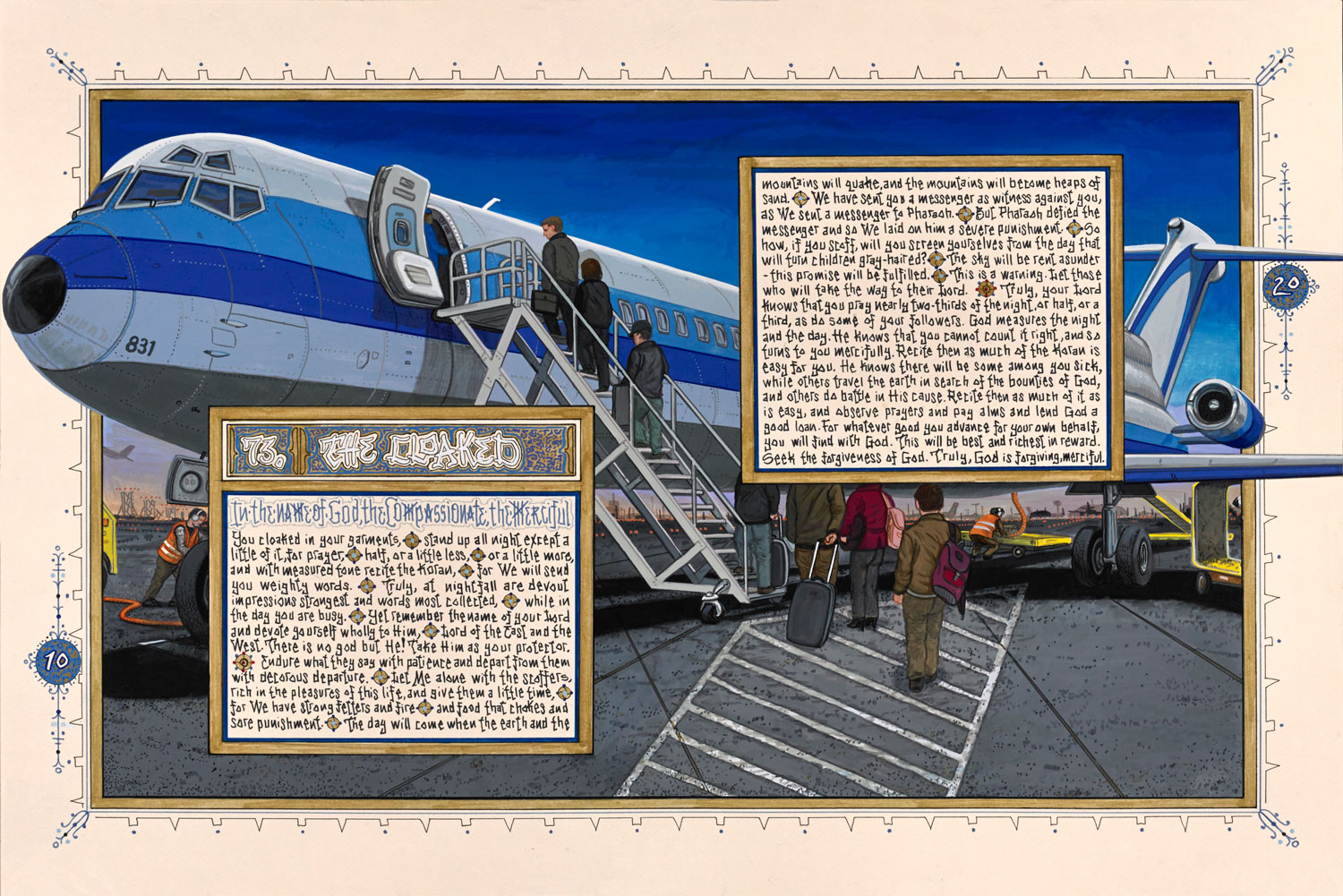

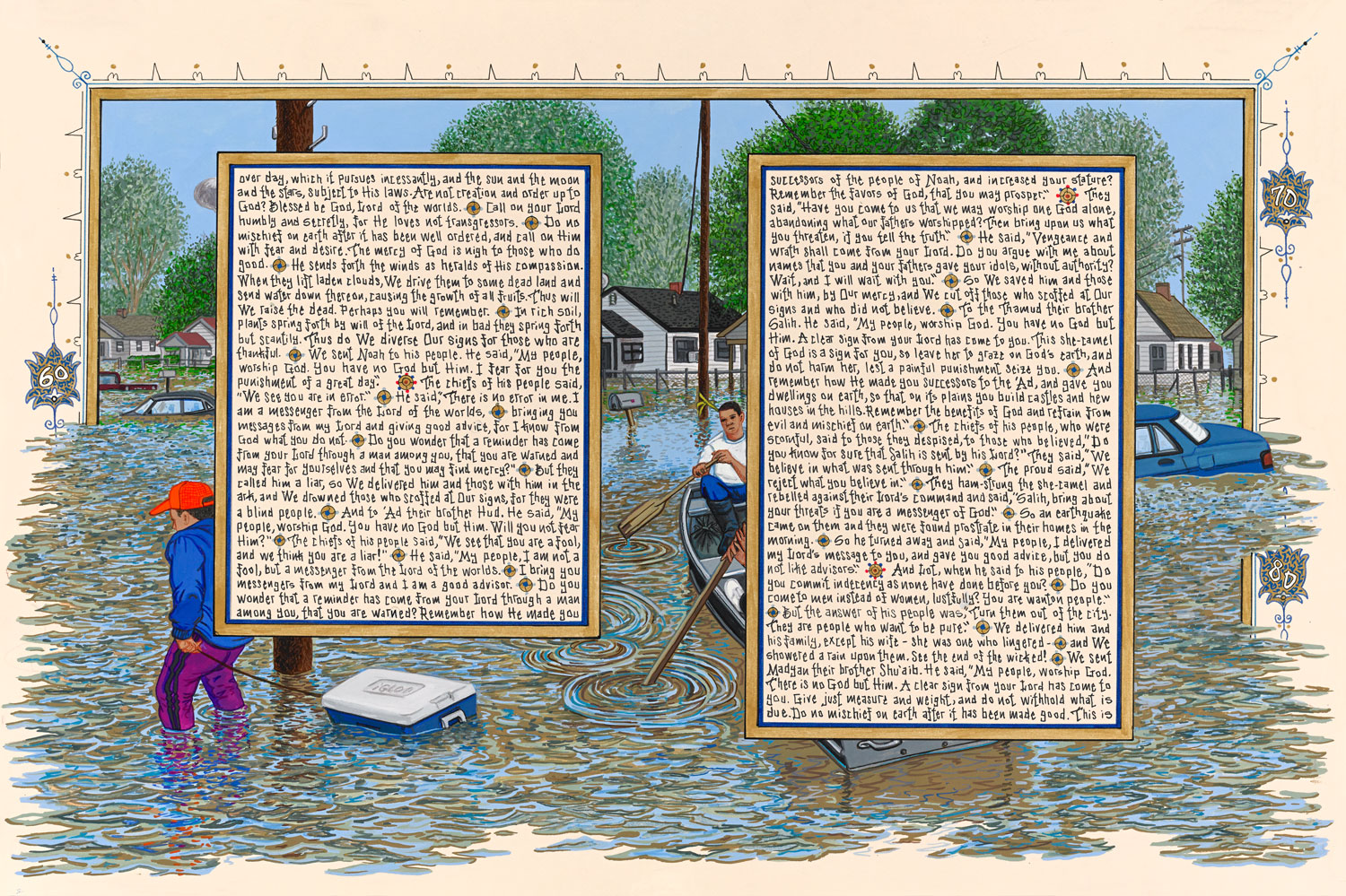

The artist created his own illuminated manuscript version of the entire Qur’an, mixing scenes of contemporary American life with the 114 suras, or chapters, of the 1,400-year-old sacred text in English translation. The work took him nine full years and resulted in a 427-page coffee-table book that’s been published by a division of W.W. Norton & Co.

“I’ve been following this project for years,” says Jill Hartz, the Schnitzer’s executive director. “We are the second museum — and the first academic museum — to show it.”

The exhibition originated in 2015 at the Orange County Museum of Art in Newport Beach, California.

Born in Detroit, Birk grew up in Los Angeles from the age of 6. “When I was a little kid I was really impressed by the beach,” he says in a telephone interview. “My parents took me to the Redondo Beach pier, and I saw surfers for the first time.”

That was a turning point in his life — and in his art. “I started surfing when I was 11 and have been surfing ever since.” As an adult, Birk has surfed oceans around the world, in such places as Indonesia, the Philippines, India and Morocco — all countries with large Muslim populations.

After graduating in 1983 from Otis Art Institute — now the Otis College of Art and Design — in L.A., he saw most of his classmates head east to make their way in the then-booming New York art world. Birk stayed home. “I was never going to move to New York,” he says. “I was a surfer!”

Instead he became a consummate southern California artist, a prolific painter of scenes, based in European history painting, depicting Los Angeles in its glory and its decadence. In one series, Birk imagines the results of a war between Los Angeles and San Francisco; in another, echoing work by 19th century landscape painter Thomas Cole, he follows Los Angeles from prehistoric times to an imagined apocalyptic future.

Birk’s work owes a debt to the hard-edged, sunny look of artists like David Hockney, as well as to the bright, clear look of cartoons and graphic novels. It also has a bit of that surfer dude sensibility.

After the Sept. 11 attacks, Birk — by then an established artist with a national reputation — began to focus his energy on the U.S. war in Iraq. The violent depiction of Islam in American popular culture, he says, had nothing to do with the Islamic people he had met while surfing around the world.

The Qur’an, which had become a hated book in the U.S., seemed key to the whole situation. “For so many people it was an evil book, a violent religion!” he says.

Birk, who is not religious, bought a copy and began to read it. He found it lovely and lyrical. Soon he began to think about creating his own Qur’an as a work of art, an illuminated manuscript in the tradition of ancient scribes.

He nearly abandoned the idea, though, as he contemplated the beauty and perfection he saw in reproductions of centuries-old illuminated manuscripts. “It would be foolhardy for me to try to make anything that rivals these,” he thought. But then, by chance, he visited Chester Beatty Library in Dublin — yes, he was in Ireland to go surfing — which houses one of the most important collections of Qur’ans outside the Middle East. He went in and looked at old manuscript versions of the book made by long-dead scribes.

“That was a big revelation,” he says. “You could see the mistakes they had made. They were handmade human objects. Not perfect.”

Starting in 2005, Birk wove text and images into more than 200 separate paintings, each measuring 16-by-24 inches, all done, like traditional illuminated manuscripts, in gouache — a kind of opaque watercolor — and ink. The Schnitzer exhibition will contain all but about 10 of the paintings; those are in the hands of private collectors.

The process was meditative. “I had to really concentrate on the text and spend a lot of time pondering it, because transcribing is much slower than just reading,” he says. “So it was a very calming and thoughtful time.” He borrowed the text for his book from several 19th century translations, giving American Qur’an a quaint, archaic flavor.

The imagery he used with the text is completely American and profoundly different from what you might expect. Birk made no effort to illustrate the Qur’an’s text in any literal way; instead he used individual suras as loose inspiration for the paintings that surround them.

Enlarge

These partly obscured paintings show every aspect of American life: Taco stands, construction workers, a wedding, a space launch, a political rally. A pregnant woman gets an ultrasound in one; in another, a man fixes a flat tire.

And, in perhaps the most dramatic image, people on a New York street look up and see one of the World Trade Center towers on fire after the first airplane has hit.

Birk was aware of the real dangers of taking on such a project. The year he began work on the project, Danish cartoonist Kurt Westergaard did a cartoon depicting Muhammad wearing a bomb as a turban; because of death threats the cartoonist has been under protection ever since. “That was disheartening,” Birk admits.

But Birk’s Qur’an doesn’t condemn Islam. It doesn’t depict, in any way, the Prophet Muhammad. In a strict sense, it is not a Qur’an at all, as it’s in English, not Arabic.

To test the waters, Birk also reached out to Islamic religious leaders and scholars, showing them the work in early stages. Finally, he took on the project out of admiration and respect. He has received little harsh criticism for his project — and no serious threats.

Birk says he thought originally it would take him four years to complete the project. After four years of work, he took stock: He was barely halfway there. In the end, producing the paintings for American Qur’an consumed nine years of his life.

“It took me a long time,” the artist says. “But every day I worked on it was fascinating. It’s fascinating as a book, it’s fascinating as a document and it’s fascinating as a religion.”

The reception for American Qur’an will run from 6-8 p.m. at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art on the University of Oregon campus. The exhibition continues at the museum through March 19. The book American Qur’an will be available for sale in the museum gift shop for $100.