Lane County, our high school graduation rates stink.

Surely that’s not new news, but what is new is the approach our schools are taking to not just pump up grad rates, but also to help kids give a damn about their education.

Perhaps the reason our high school grad rates have lagged behind some neighboring counties (not to mention they pale in comparison to the national average) is because we’ve failed to put the students first. Programs like Career and Technical Education (CTE) are working their butts off to change that.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the national average for high school graduation has lingered around 80 percent since 2013 and hit a historic high of 81 percent in 2015. As the national average rose, so did Oregon’s — however bleak the starting point.

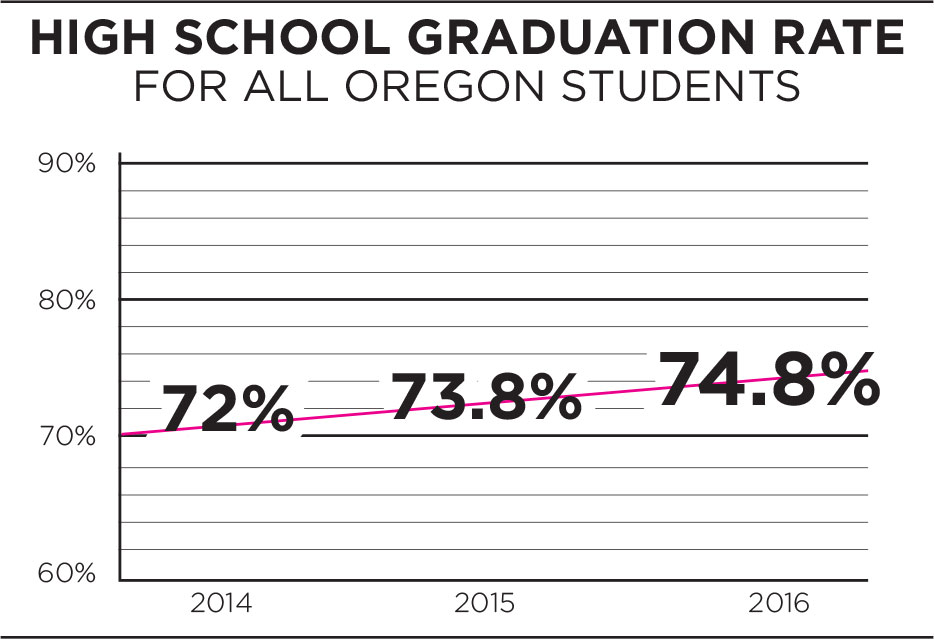

The Oregon Department of Education reported in 2010 that our state’s overall high school graduation rates stood around 67 percent. By 2013, grad rates had climbed to 68.7 percent, and the number continued to bumpily rise until we hit our pinnacle of 74.8 percent this past year in 2016.

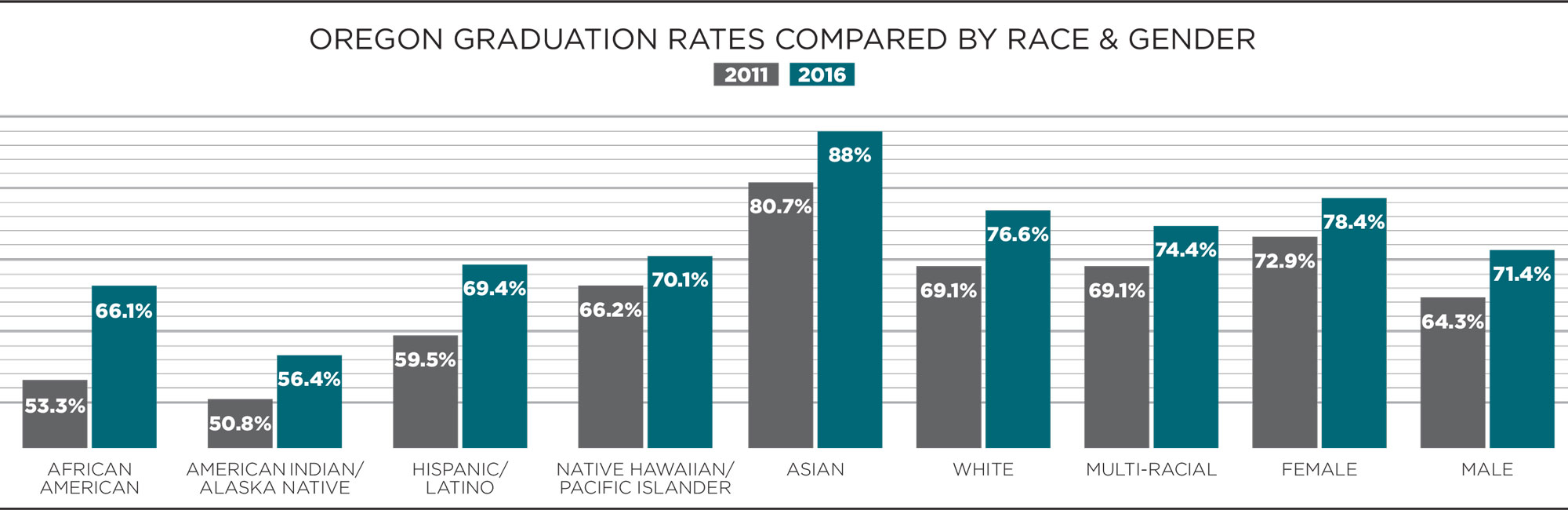

These rising rates include students of minority ethnicities, varying abilities, gender identities and English proficiency levels.

The Eugene School District reported that Lane County hit a 72.4 percent graduation rate for the 2014-2015 school year. At the same time, our neighboring Linn County districts graduated 84.8 percent of students, according to ODE. Lane County is far more populous than Linn (77.2 people per square mile in Lane versus 50.9 according to the most recent census data) but both counties have similar median incomes for households, around $44,000-$45,000.

One difference between the counties’ grad rates is the number of programs offered to the kids, especially CTE programs. Linn County districts offer a wide array of CTE courses that range from the arts to automotive work; the courses get kids involved with local companies before they graduate.

In short, CTE helps answer the infamous question that every bored high schooler utters: “Why am I learning this?”

Of course skipping class or zoning out during a lecture is way more appealing than sitting in a stale classroom with no clear need for the information you’re being taught by overworked and underpaid teachers.

Enter CTE’s new efforts in Lane County, which aim to lessen the load for busy teachers and help engage kids across our county’s 16 districts. Over the past several years, the Lane Education Service District has been expanding CTE courses and adapting the program to meet the county’s economic needs as well as its students’.

“Every district is going to do things a little bit differently,” says Heidi Larwick, director of Lane Connected, a program that keeps high school programs aligned with local college curriculum. She works closely with CTE directors, “so we’re trying to supplement what they’re doing with more efficient practices.” Lawrick explains that the CTE program has been reworking more centralized efforts to partner with local businesses for the program instead of putting the weight on teachers, counselors or individual high schools.

Larwick says Lane schools have roughly one counselor for every 350 students. When counselors have more work outside of school, she says, they have less energy for students — something that has overwhelmed districts in the past. She explains that teachers and counselors will have more time to focus on their students as well as being able to provide them with more internship and practical learning opportunities among local businesses partnered with CTE.

CTE has 69 programs in Lane County and is partnering with 25 local companies that have agreed to host internships, job shadows and site visits for high school students this spring and summer. Most of the programs focus on the growing technology industry in Eugene, but opportunities in the arts, design, marketing and public broadcasting are also available to students.

“There’s an element of getting kids excited about something, and I don’t think they know enough about our local opportunities,” Larwick says. “When you give them something to dream about, they get excited to come to school because they’re learning about a passion of theirs.”

Carlos Sequeira, head of Instruction, Equity and Partnerships (formally known as School Improvement) at Lane ESD, says Lane County has consistently done a poor job of justifying why kids should be passionate about what they learn in class. Sequeira says that CTE’s expansion will better serve the students by accommodating their various needs.

“We want to improve the outcomes for each and every student,” Sequeira says, “and find out what that looks like in terms of the curriculum and instructing we are providing for our students.” He says that his department, which collaborates with CTE, is taking a closer look at students who come from stable homes and who traditionally have more opportunities than marginalized or lower income students. The latter groups tend to be the students who fall through the cracks of academia, thus negatively impacting graduation rates, Sequeira explains.

Achieving better graduation rates means better funding for adequate curriculum that accommodates to a diverse pool of students. “One initiative is Math In Real Life, which is a statewide approach that intends to improve math instruction equity,” he says. “Meaning that we want to explore, honor and integrate the language and culture of the student into every day instruction.”

Math In Real Life was awarded the STEM (Science Technology Engineering Math) Innovation Grant, which, according to ODE, allots $250,000 to a single regional project and runs from March 1, 2016, through June 30, 2017. Linn County was awarded the Carl D. Perkins Grant, which supports CTE programs and has a proposal-dependent amount. Lane County was awarded a $950,000 chunk last year, however, in 2016 the county did not make the list.

Although the new CTE initiatives are still fresh, graduation rates in Lane County have been rising in tandem with the expansion and involvement of CTE, as well as the statewide emphasis on equitable teaching practices.

The challenge of communicating with students in a way that makes them feel supported as well as motivated in the classroom, Sequeira says, is not unique to Eugene or Lane County.

“It’s a state and nationwide question about how we engage with our marginalized students,” he explains. “It’s about how we connect that bridge between what they value at home and what our teachers value. Do their pedagogical beliefs match the students they’re serving?”

Help keep truly independent

local news alive!

As the year wraps up, we’re reminded — again — that independent local news doesn’t just magically appear. It exists because this community insists on having a watchdog, a megaphone and occasionally a thorn in someone’s side.

Over the past two years, you helped us regroup and get back to doing what we do best: reporting with heart, backbone, and zero corporate nonsense.

If you want to keep Eugene Weekly free and fearless… this is the moment.