When I walked through The Duck Store the Wednesday before classes started at the University of Oregon, I saw a sea of searching faces. Athletic apparel might subsidize the nonprofit store’s bottom line, but during week one, students are shopping with a mission: getting books so they don’t fail their classes. That mission is made more difficult by the high price tag attached to these required precious commodities.

Wandering down the first aisle, I overheard a student on the phone talking about how she had to buy a book written and assigned by her professor. It was hard to tell whether she was more indignant about the cost or the professor’s gall to assign his own book.

Two other women, both UO seniors, were buying a geology textbook to share. “New it’s $110.50. And it’s paperback,” Sophia Meyer, a public relations major says. Another option for these women is to buy the book used for $83 or rent it from Amazon for $86. Regardless of how they get their hands on it, debt in the form of credit cards and student loans come into the equation.

The Duck Store lists roughly 3,500 different titles every year, according to Gina Eckrich, the course materials buyer for the store. Eckrich says that roughly 30 percent of the books are used and 70 percent are new, including bundles and online access codes.

Each term, The Duck Store is given a list of books that it will be expected to carry. These lists are generated by professors and instructors. Alex Lyons, chief information officer for The Duck Store, says they work with five to seven wholesalers to get those books. These wholesalers determine how much books will cost students, Lyons says. Some of the books are allotted for rentals; however, only those books that the wholesaler will accept back at the end of the year can be rented to students.

Wholesalers will take back only certain books each year, and part of that turnover is new editions of books on the same material. “You kind of have to decide,” Meyer says. “Do I do bad in this class, or do I spend $200 on this third edition of this textbook that the teacher says we need because they take the homework from that specific edition so you can’t get a cheaper one?”

Last fall The Duck Store rented more than 10,000 textbooks to students.

Anyone who has gone to college or talked to a college student about textbooks knows there are hard feelings about the hundreds of dollars spent every 10 to 16 weeks on top of tuition. While publishers continue to set the price of books as well as the brick-and-mortar stores that carry them, everyone is taking a financial hit.

According to its non-profit tax reports, The Duck Store has seen total revenue decline from $38,762,508 in 2013 to $29,822,399 in 2015 — the latest available data. Lyons says that used bookstores, à la Smith Family down the street, don’t cut into The Duck Store’s bottom line as much as online retailers such as Amazon. The online mega-retailer is taking a loss as well, Lyons says, but a multi-billion dollar company can more easily afford to take those losses than smaller stores.

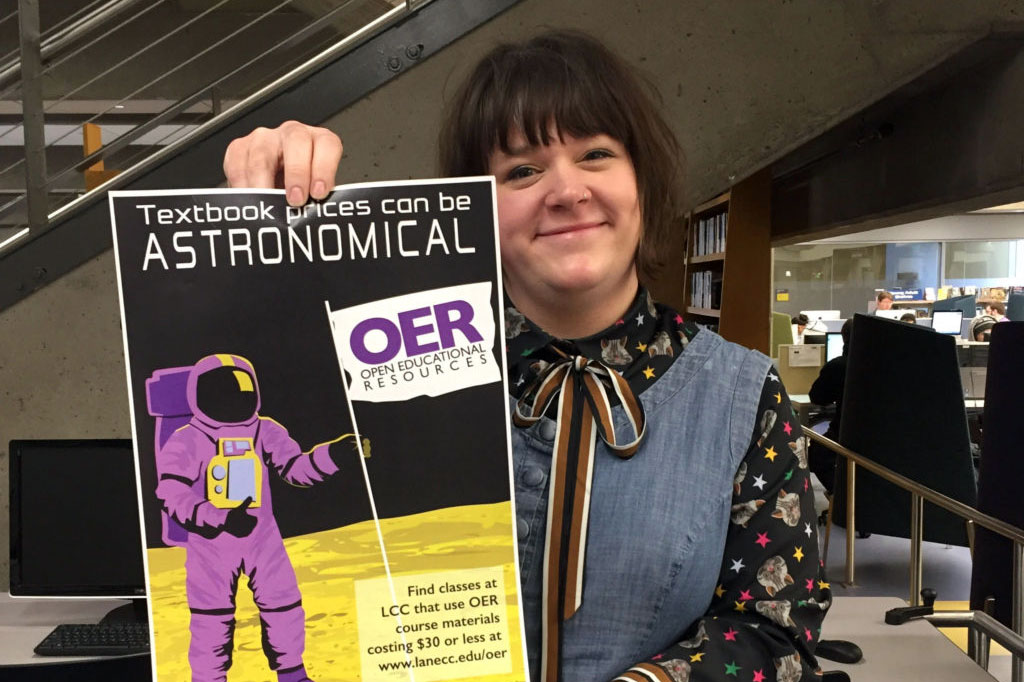

In order to circumvent these costs — and losses — some instructors at Lane Community College are relying on Open Educational Resources (OER).

Meggie Wright is the OER librarian at LCC. She is working to educate students and instructors about what OER are and how they can take advantage of those resources. “The piece about OER that’s easy to understand and grasp is the textbook affordability piece,” Wright says. “OER is available for free in a digital format.” While all written material has a copyright, OER have open licenses, meaning anyone can use or change the material to suit their needs and they can do so for free.

Wright says that use of OER textbooks is picking up steam at LCC, but some instructors have good reasons to be hesitant. Textbooks come with additional resources for teachers — Powerpoint presentations, homework assignments and tests, to name a few. For this reason, Wright says, a lot of work is involved for instructors who might want to shift to unsupported and sometimes unrelated material in OER books.

While instructors and professors wrestle with course material selection, students will continue to fight to get their hands on the books. The most extreme cases can look as drastic as skipping meals to pay for books but other struggles play out too.

“I’ve definitely been late on rent after spending $300 plus on books,” Meyer said.

Brooklynn Spooner, Meyer’s friend she is buying her geology book with, said she has sacrificed grades because having the book before classes start is difficult. “If reading was assigned that first lecture, you didn’t have it done or turn in something, you sacrifice your grades which is what you’re here to get,” Spooner says. “It’s expected that you already have $110 to blow on books, and tuition is — already on top of that — expensive.”