On a gray winter day, mist hangs above the hills that surround Eugene. From the eastern end of the Ridgeline Trail, which runs along the hills that form the south flank of the city, a ribbon of clearcut forest winds its way from Spring Boulevard down toward Lane Community College.

A newly paved driveway accesses building sites next to the upscale residences of the South Hills. These new homes will be built in an area that’s supposed — under Oregon’s land planning laws — to support a working forest.

Instead, the land is being developed because Lane County land-use rules allow nearly forgotten scraps of historical records to turn forestland into new residential developments.

By resurrecting old deeds, savvy developers establish new lots, reconfigure the lots and then apply for special permits that allow development in forestlands. The land above LCC, which is owned by the McDougal brothers of Creswell, is a recent and particularly visible example of this controversial technique that often results in McMansions instead of trees.

Developments like these have long frustrated land-use watchdogs and unsuspecting neighbors. That’s because they aren’t subject to the same public processes as typical rural developments, such as a public comment and appeals process or requirements that new houses won’t harm the use of neighboring wells.

These frustrations also stem from Lane County’s history of approving far more of these developments than anywhere else in the state and the perception that Lane County commissioners support development to the detriment of zoning laws.

Understanding the process that allows these developments is a trip into the past and through a series of land-use laws and procedures. It’s easy to get lost in the weeds of detail, but these policies have tangible consequences for those who want to see forestland stay forested or who might have their well run dry after a new neighborhood pops up next to their land.

Whether the county will crack down on this controversial development tactic or proceed with business as usual is a matter of contentious debate between incumbent county commissioners and challengers hoping to shake up the status quo.

Historic Legal Lots

In the cavernous concrete building that houses the Lane County Courthouse, the Deeds and Records department gives a glimpse into the past with modern implications. Reams of paper and microfilm reels hold clues that can give new life to land ownership decisions dating back to before Oregon’s statehood.

Among the Lane County property records are more than a 150 years of land-use division decisions about which the county itself lacks knowledge of all the details. Instead, the county has an application process that puts the onus on property owners to prove what lots they own.

Each modern lot has a unique and often complicated history. You can think of each lot as a kind of flip book: On the first page you see the modern tax lot that is on file with Tax and Assessment. The tax lot defines the current boundaries of a property and dictates how much and who pays taxes on the property.

As you flip back through the years, in many cases, the boundaries shift on what was once a solid chunk of land. Old sales and land divisions appear: Perhaps a family member wanted to gift a daughter or son a chunk of their property or maybe a nearby rancher bought a piece of a neighbor’s land to have more grass to graze.

In some cases, changes in the curvature of a road can justify the creation of a minuscule new lot under Lane County code.

As you get to the end of the book, Donation Land Claims and Homestead Act land grants of 160- to 640-acre parcels from the early years of and even before Oregon’s statehood, appear. Each of the boundaries in old land division decisions, if they are on record and can be proven to be legally created at the time, can justify the creation of modern legal lots.

How the Deeds are Found

The framework of Oregon’s statewide land-use system was developed in the late 1960s and over the course of the 1970s. Republican Gov. Tom McCall captured the spirit of the land-use reform movement in 1973 when he called on lawmakers to enact stricter land-use laws to protect Oregon from “the grasping wastrels of the land.”

Following statewide legislative reform and facing resistance from anti-sprawl advocates, Lane County took years to develop a land-use plan acceptable to state regulators.

The plan, which included a system for verifying legal lots using historical records, went into effect in 1985, Donald Nickell’s first year working for the county.

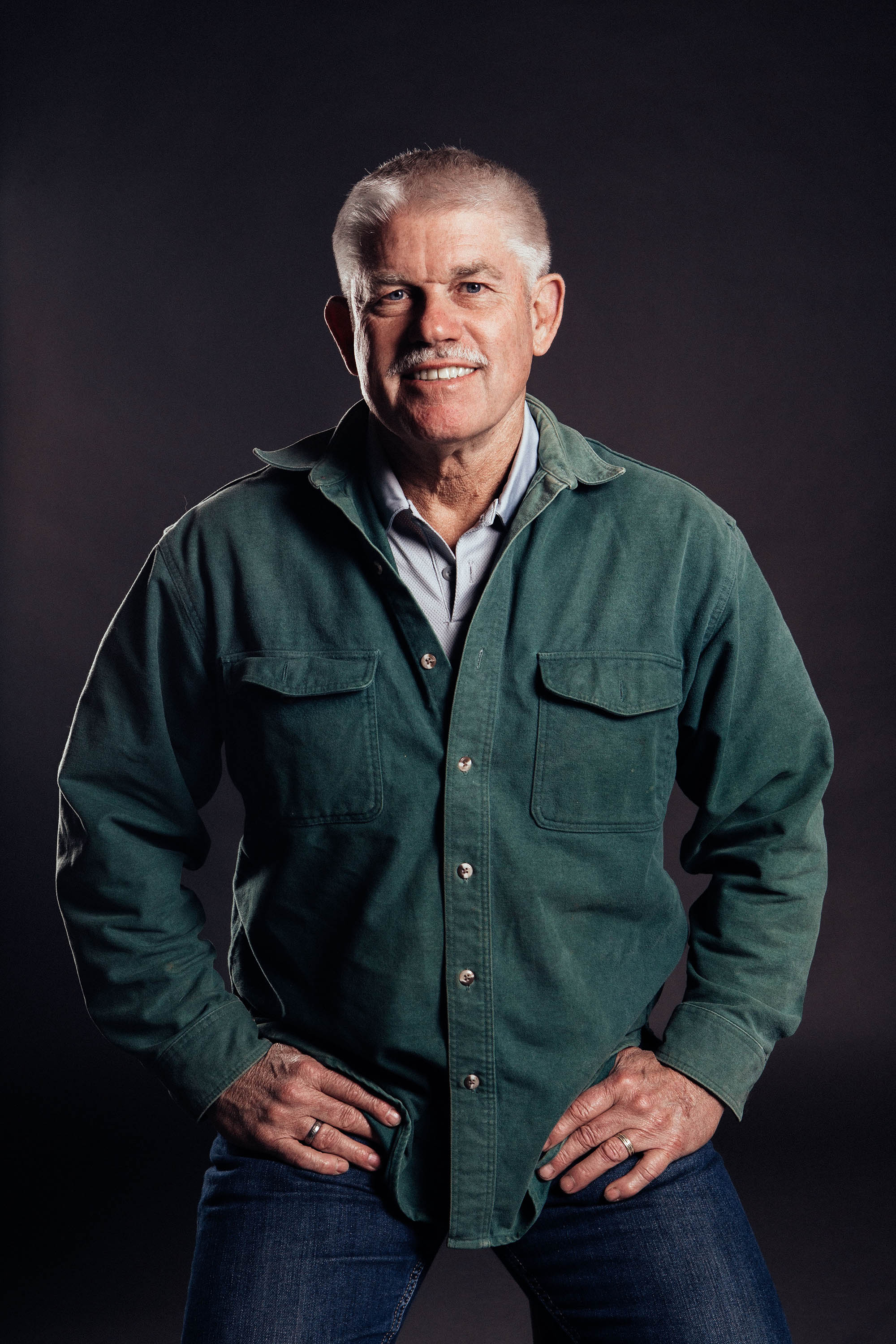

Nickell carries a briefcase of files from his private surveying business to help describe to Eugene Weekly the process of legal lot verification. From 1985 to the end of his career with Lane County in 2007, Nickell was responsible for verifying legal lots for the county.

Today, employing the knowledge he gained working for the county, he owns and operates a surveying company that helps landowners and developers navigate the legal lot verification system.

Lauri Segel-Vaccher, who works with the land-use watchdog group LandWatch Lane County, says her organization has serious concerns about the way the county approved historic legal lots during Nickell’s tenure. They argue developers were granted lots based on preliminary decisions and that the process lacked transparency and thorough findings to back up the creation of new lots from historic deeds.

Enlarge

Photo by Todd Cooper

But Nickell says that in his time with the county he never lost an appeal challenging his findings. As someone who was there when the county developed procedures and protocols for recognizing legal lots, Nickell is very familiar with the county’s legal lot verification process.

While we may think of a surveyor’s work being done by tromping around properties looking for old stakes, the process of legal lot verification is more akin to library research. Nickell compares the process of searching for legal lots to an investigation. “You have to know where to look and what to look for.”

The main tools are the Assessment and Taxation Description Card and the binders and reels of property records held in the Deeds and Records office.

By cross-referencing old property transaction dates with the details of the transactions, Nickell is able to determine whether landowners can establish new legal lots on their property. Nickell says he usually knows if landowners are likely to find additional historical lots within an hour.

He says he doesn’t seek out properties with historical lots, but says “it just comes out in doing the work.”

When Nickell or another surveyor or land-use attorney find old legal lots, they fill out an application form with Lane County Land Management to have the lots recognized as separate legal lots. Neighbors are notified of these applications, but there is no public comment process and often little understanding of what the designation of new legal lots means.

Once lots are recognized by the county as separate entities, they are not guaranteed development rights, but they are subject to different land-use standards that can pave the way for new development with the potential for changing forested lots into McMansions.

From Legal Lot to Development

Lands that are zoned as forestland have restrictions on residential development that are meant to maintain forests and promote timber industry uses.

In “impacted forest lands” or F-2 zones, newly created lots or parcels cannot be smaller than 80 acres, and each parcel can have only one residential dwelling. Limiting lot sizes to 80 acres greatly reduces the development potential of properties, which is why rediscovering lots from the past can be a major boon for developers who want to build more houses.

The restrictions that apply to larger lots do not apply in the same way to smaller lots created through the historical lot verification process. If a landowner has historical lots approved on their property, each lot can be smaller than 80 acres and eligible for a new dwelling.

At the development by the McDougals above LCC, one of the historical lots is from the turn of the 20th century. The lot will come back to life and undermine state zoning laws aimed at preserving forestland and limiting sprawl.

Developers can create mini-subdivisions on lands that are supposed to be kept as forests, because once landowners have established multiple legal lots on a larger swath within their ownership, they can move the lots into a more development friendly configuration.

Forest Template Dwellings

In lands zoned for forest use, dwellings can be approved under certain restrictions described by state law. Within the guidelines of state law, counties have the right to make more restrictive requirements but cannot be more lenient than state law, according to Gordon Howard, the community services manager for the Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development (DLCD).

One area that is an issue for the DLCD in terms of maintaining forestlands for their intended use is template dwellings.

Template dwellings are one of the types of residential development that are allowed in forest zones. The law is supposed to limit template dwellings to one house for every 80 acres of zoned forestland, but small lots created through the lot verification process are each eligible for forest dwellings under Lane County’s development guidelines.

Oregon’s state land-use goals set expectations for how land should be managed to satisfy different values, from maintaining farm and forest to providing an adequate and affordable housing supply.

As the agency responsible for seeing that land-use goals are met, the DLCD raises concerns about the development of template dwellings as a result of old lots’ getting new life. That’s because the development of estate-like properties in forestlands isn’t compatible with the state’s Goal 4, which says, “Developments that are allowable under the forestlands classification should be limited to those activities for forest production and protection and other land management uses that are compatible with forest production.”

Residential developments in forestlands deplete already stressed groundwater resources, increase the costs and danger of protecting homes from wildfires, reduce the carbon storage potential of forestlands, and shrink and fragment wildlife habitat. And expensive rural developments are not a realistic or affordable means of addressing shortages in the housing market.

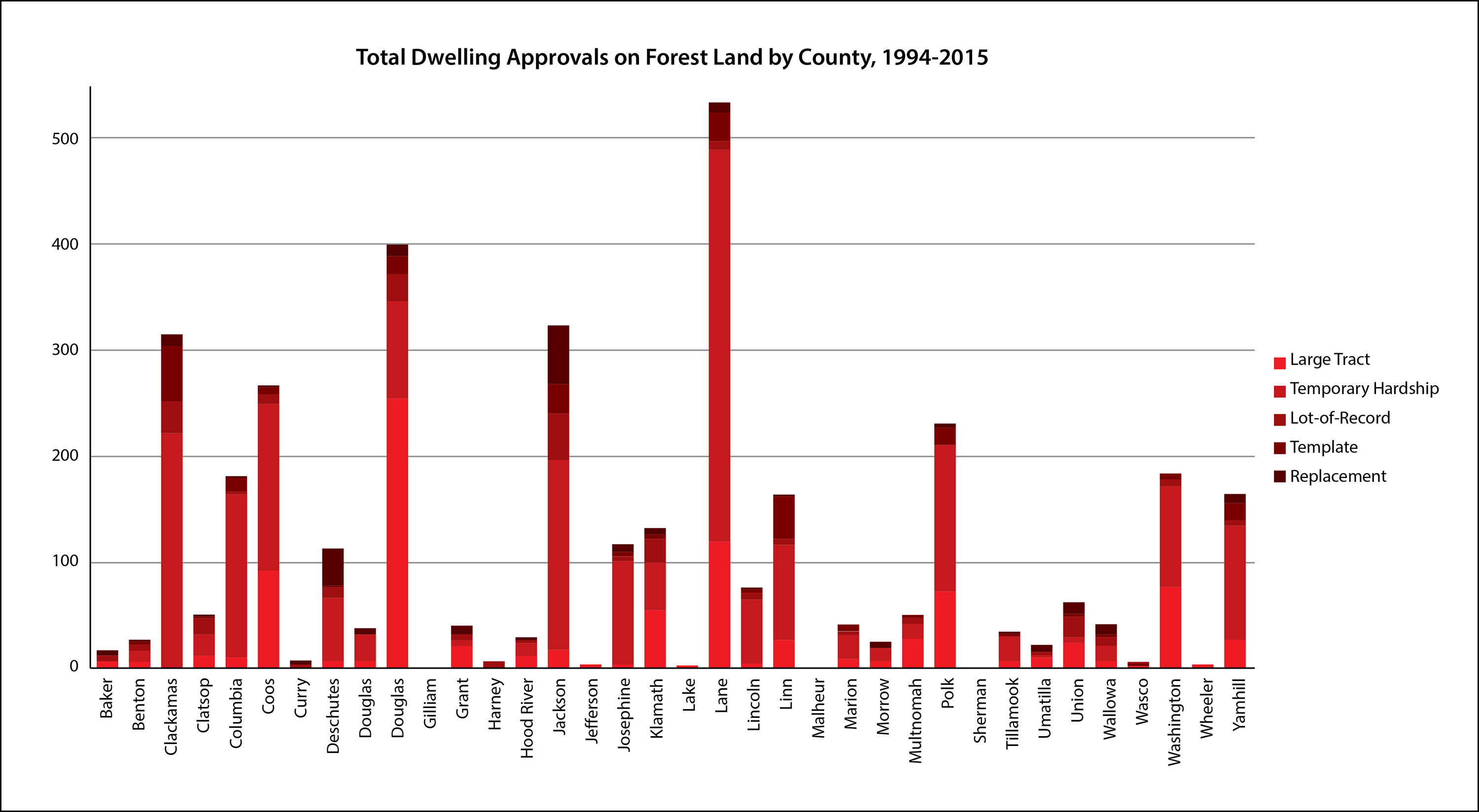

According to a January 2017 DLCD report, a third of the approvals for forestland development of template dwellings statewide between 2014-2015 were in Lane County. The county’s 91 approvals for this type of residential development was triple that of the next highest — 27 in Coos County.

The disproportionate amount of template dwelling approvals from 2014-2015 is not an anomaly for Lane County, according to the DLCD. From 1994-2015 the county’s nearly 350 approvals for template dwellings surpasses the next highest number, in Clackamas County, by more than 100.

While there are other factors, such as housing demand and large amounts of publicly owned land in the county, the county’s system of recognizing old deeds and approving template dwellings makes the development possible.

DLCD farm and forest specialist Tim Murphy says the agency is not claiming, as some land-use watchdogs do, that Lane County’s process breaks the rules. But the DLCD recognizes that tying the creation of properties to a certain date in the past, and not back to before statehood as Lane County does, would help limit these developments and preserve forestlands for their intended uses.

Murphy says that restricting the use of historical lots to create new developments would likely require an amendment to state statute. And any amendment doing so would be difficult to pass because of measures 49 and 56 passed by state voters that limit the state’s ability to reduce property value and limit development.

DLCD’s Howard says the measures reduce the likelihood of the state Legislature addressing this issue. The measures require either compensation or notification to landowners if changes in state law affect the development potential of private land.

Serving Its Purpose or Cause For Concern

While there is a gap between the intended use of forestlands and the types of developments being allowed in Lane County, land-use planners say that, while not perfect, the system is working. Lane County land planning supervisor Keir Miller and division manager Lydia Kaye say there are concerns with parts of the process, but that changes would require new policies from the Lane County Board of Commissioners and could prove costly.

“From a staff perspective we recognize that there are certainly some challenges with the way the legal lot verification system has evolved over time,” Kaye says. “I think these are some of the good conversations we want to be able to have with the Board of County Commissioners.”

Kaye says she encourages people to show up to commission meetings and give their feedback on these policy issues.

She says the commissioners are hearing about the issue from both developers and land-use watchdogs and “ultimately the policy direction will be set by the commissioners.”

Commissioner Pete Sorenson told EW via email that he is “very interested in participating in a board discussion” about the approval process for template dwellings and the historic legal lot verification process. He writes that it doesn’t make sense to him to have historic legal lots supersede modern zoning requirements.

Sorenson also writes that he is concerned about more dwellings in forested areas, “as I see the forest/residence proximity to be a factor in forest fire risk and forest fire deaths.”

The other Lane County commissioners, who were emailed the same questions as Sorenson, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Reforming the Deed System

Segel-Vaccher of LandWatch Lane County says that the county could take three major steps to control forest development and reform the historic legal lot verification system.

The first reform would be to require developers to submit development plans at the same time they submit requests for legal lot verifications. Segel-Vaccher says that residents often don’t understand the implications of legal lot verifications and end up shocked by developments down the line.

“They give notice of pending decisions to the neighbors,” she says, “but no one understands the implications and it’s very hard for a normal person to challenge it. It costs $250 for the first appeal.”

If developers or landowners were required to submit legal lot verifications in tandem with development proposals they would trigger a public comment period. Segel-Vaccher says this would help by allowing neighbors and others to provide input and help them understand the development implications of the legal lot verification process.

Another reform LandWatch would like to see the county put in place is the establishment of a minimum lot or parcel size for developments in forest zones. Segel-Vaccher argues that state zoning laws did not intend to allow small lots and developments in forestland and that enacting a minimum lot size for development would stop clustered developments like the one at LCC.

The final reform LandWatch recommends is to require landowners to establish water availability for any new forest dwelling. Because forest dwellings are permit decisions, rather than land divisions or zone change decisions, they do not trigger the same criteria for aquifer tests that establish water availability and require that new wells do not impact the water availability of their neighbors.

New developments don’t only mean higher withdrawls from already stressed aquifers, they also lead to less replenishment to aquifers because of higher levels of runoff and loss of forest cover. Though Lane County doesn’t typically have a shortage of rainfall, the geology of much of the county leads to unreliable aquifers and at times dry wells by the end of summer.

In 1982, the county’s own water resources working paper stated, “Eighty percent of the County is subject to serious groundwater quality or quantity problems, or both.” Since then more than 300 additional residences have been developed in forestland without requiring studies to prove they won’t impact neighboring well-users.

Requiring the same standards for groundwater use to be applied to forest template dwelling developments as land divisions and rezones would help protect neighbors who could see their wells run dry because of new development.

In The Hands of the Voters

Drive down 30th Avenue and glance over at the hill by LCC, look at the scarred clearcut and picture the forest that used to be there. Now picture the hills dotted with McMansions, one after another, outside Eugene’s urban growth boundary designed to keep sprawl under control.

Enlarge

Photo by Todd Cooper

Reining in this rural sprawl and putting in place new measures to protect neighbors and maintain forestland is ultimately up to the people of Lane County and the elected officials on the Board of Commissioners. Three of the seats on the five-person board are up for grabs in May, and developers are putting their money behind the incumbents.

The McDougal Bros Investments company, which uses legal lot verification and template dwelling to develop zoned forestland in Lane County, is a major supporter of the incumbent commissioners. The McDougals donated $10,000 each to commissioners Sid Leiken of Springfield and to Jay Bozievich, who represents western Lane County.

While the incumbents are unlikely to rock the boat and usher in land-use reforms that would damage their primary campaign contributors, the challengers have shown interest in reshaping how Lane County deals with forestland development.

Candidate Joe Berney, who is running against Sid Leiken for the Springfield seat, is in favor of closing the loopholes in county code that allow developments like the one above LCC.

In a written statement to EW, Berney says, “I am in favor of exposing the loopholes, reviewing them publicly and transparently, and then closing them.” He says that before this issue came to light, “I’m sure the only ones who knew of these loopholes were wealthy developers who had legal and planning staff to figure them out.”

East Lane County Commissioner candidate Heather Buch says she worries that projects like the clearcut and development at LCC can lead to more complicated regulations in the future and further complicate county development codes. She writes to EW that the complicated code requirements of Lane County and high housing demands “can lead to development outside metro areas, forcing unanticipated burdens on rural communities and the environment.”

“It is unfortunate that large swaths of these valuable lands disappear by folks exploiting loopholes in our code and without transparency to the surrounding community,” Buch writes.

Kevin Matthews, who is also running for East Lane County Commissioner, says that it “is sad to see the county board let special interests cheat the rules to make short-term profits.”

“It’s notable that two of the commissioners facing an election just got big contributions from the McDougals,” Matthews says. “It is a shame to see elected officials support their piratical land development behavior.”

“The fundamental question is administering land use fairly,” Matthews says. “If they want to change the rules that’s one thing, but to break down the rules through shady interpretations is a bad way to operate local governments.”