Once upon a time, photography was a simple affair. The photographer’s job was basically to record light onto a surface. Fun fact: The word photography combines the Greek terms for “light” and “drawing.” Of course, there was a bit more involved, but that was the essence.

Over time the situation has gradually grown more complicated for photographers, especially in the past century as “light drawing” has become assimilated into the art world. For anyone curious about this shift, the two photography exhibitions currently showing at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art make a good case study. One is rooted in the past, the other in the present. They sit in adjacent rooms upstairs at the museum, separated by a thin door and a thick shift in paradigm.

Let’s consider the past first. Weegee’s Grief and Joy squeezes a small selection of photographs into the Morris Graves Gallery upstairs. The 13 small prints on display offer a “greatest hits” tour of Weegee’s career. If you’re unfamiliar with Weegee, this show will quickly catch you up to speed on a few key highlights. For those who already know Weegee, seeing these prints in person will confirm his brilliance.

The show is curated by Lucy Miller from a major gift of 85 Weegee photos given to JSMA recently by Ellen and Alan Newberg. That would be the same Ellen whose name is scrawled by Weegee on the show’s first photo: “To Ellen, Photographer and Model, Weegee.”

Ellen Newberg had an inside track on Weegee prints. Her aunt was Wilma Wilcox, Weegee’s longtime assistant and partner. Wilcox’s collection passed to Newberg, and then to the JSMA in 2016. This is the photos’ first public curation since. It’s a good start but severely abridged, and leaves the viewer wanting more. For the time being there’s Grief and Joy.

“Weegee” was the adopted nickname of Arthur Fellig, who made his name as a Manhattan press photographer in the 1930s and ’40s. His photographs ran in newspapers and magazines of the time, but their artistic edge set them apart from run-of-the-mill reportage. Along with an uncanny nose for developing photo ops (the name “Weegee” refers to his Ouija-like prescience) Weegee possessed an innate sense for framing and timing and a reporter’s instinct for the sensational.

But perhaps what best distinguished his photographic voice was his wry sense of humor, an openly ironic outlook better suited for Generation X than the Depression years. Looking at the JSMA photograph Window Shopper (1930s-40s), it seems some part of Weegee Ouija-sniffed the distant slacker future in the wings. Its subject, a bearded flaneur, fits equally well into the 1930s or the present. In fact, I could swear I saw that guy just yesterday near the library.

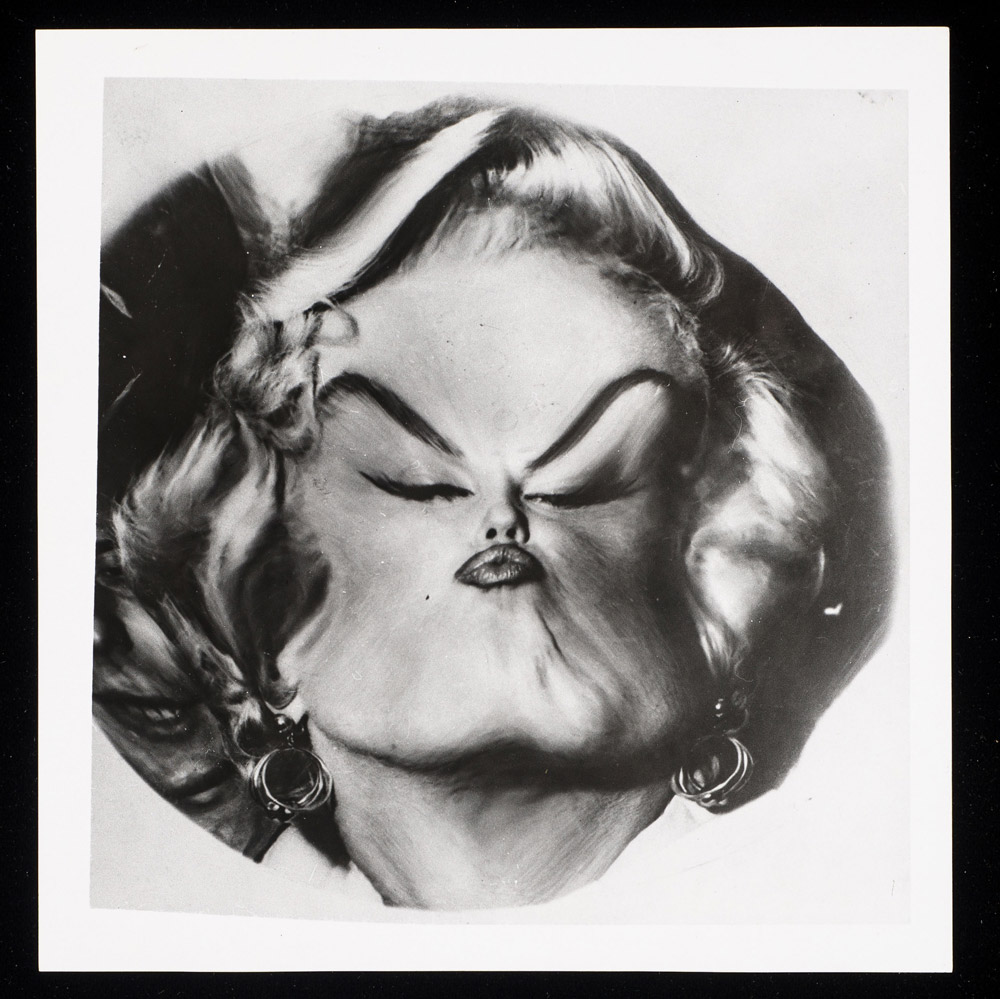

In photographs like The Critic (1943), and Simply Add Boiling Water (1930s), both on display here, Weegee makes no attempt at subtlety. He was openly comedic and proud of it. No art-school coyness for this New Yawker, just jokes in your face, and good ones at that. Later in his career Weegee’s wit would morph into a surrealist/absurdist vein, visible in the show’s final two prints, Marilyn Monroe (1960) and Balancing (1960s). Such absurdism is still a component of the contemporary photo scene, but unfortunately the sharp visual puns of Weegee’s heyday have largely been eradicated.

Which brings me to the JSMA’s other photo show, Rodrigo Valenzuela’s Work in its Place, showing adjacent to Weegee in the Schnitzer Gallery. If the Morris Graves Gallery has the stuffy intimacy of a walk-in closet, the Schnitzer Gallery is a dozen times more spacious, with airy ceilings and large windows allowing natural light to spill onto the parquet floor.

In its center Valenzuela has commissioned a large scaffold, “an enclosed tower,” as he calls it. It’s an impressive structure of bright wood and tight joints, a work of art in its own right.

Valenzuela’s photographs hang along its outer wall. The inside of the frame is reserved for the show’s curatorial jujitsu: a collection of landscapes handpicked from the JSMA’s archives by Valenzuela, “an inaccessible cabinet of curiosities,” as the museum calls them.

In contrast with Weegee’s curation, this is decidedly not a greatest hits collection, but instead a personal assemblage with all its quirks and idiosyncrasies. The selection is wide ranging, with paintings, photos, prints and a few sculptures. The very act of curating them is integral to Work in its Place, a facet which might unnerve a photographer from Weegee’s era.

The twist is that the curated interior works face inward away from the viewer. This presentation strategy seemed to me bizarre at first glance, literally bass-ackward. But it slowly grew on me and even became revelatory.

Enlarge

Gift of Ellen and Alan Newberg

Until seeing this show, I hadn’t quite realized all the different ways artists marked the backs of their creations — presumably the side meant not to be seen — all of them re-marked again by the museum for storage. The effect is literally remarkable. It’s a view behind the museum’s curtain, one that is maybe not illicit but yet feels transgressive, like being let in on a secret.

Valenzuela’s photographs may also have secrets, but, if so, they’re not in the presentation. His photos face out toward the viewer. They’re large, roughly 4 x 5 feet in size, forcing the viewer back a few feet to take them in. It’s from there that the juxtaposition of the interior and exterior material — the curated works and Valenzuela’s originals — becomes the meat of the show, creating an entertaining dynamic as one circles the scaffold. Various interior pieces, or pieces of them, pass in and out of peepholes while Valuenzeula’s remain in view.

Valenzuela’s photos depict various views of California’s Zabriskie Point, a nondescript place to begin with, to which the photos seemingly don’t add much. They’re too abstracted to convey specific details.

If the aim of Weegee’s printing was to clearly communicate what he saw, Valuenzeula takes the opposite tack. His photos are heavily mediated through laser printing, tonal transfer, scrubbing and general tweaking. They feel more like paintings than photos, and maybe they are, depending on one’s definition. Photography, welcome to the art world.

Work in its Place feels quite contemporary, a few distinct generations removed from Weegee’s simple world of “light” plus “drawing.” In the intervening decades photography has become a multidisciplinary process involving curation, identity politics, material and production choices, marketing … and large wooden scaffolds. It’s come a long way since Weegee, and I can appreciate all the changes. Nevertheless, I still have a soft spot for “light drawing.”

Weegee’s Grief and Joy: Selections From the Collection is on display through July 1 and Rodrigo Valenzuela: Work in its Place is on display through August 5 at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon.