I realize it’s a fairly risky proposition, in these strange days of division and disruption and “fake news,” for a journalist to beg your trust, but I can only ask that you trust me on this one thing: There is nothing not good about a bunch of high school students being taught the rigors of journalism. I dare say it should be part of every secondary curriculum. We are nothing if not creatures of the media these days. Best get on top of it.

As a lifelong journalist of no particular distinction save a smoldering passion for freedom of expression, I can say that my high school newspaper saved my life. It taught me to think. It taught me to speak. It taught me to care. It taught me to question. It taught me how to work well with others.

Gumption, grit, collaboration and curiosity are the hallmarks of journalism well practiced, and these are exactly the qualities I encountered when I first walked into Ivan Miller’s classroom at Springfield High School. These kids were engaged, and they were busy.

Enlarge

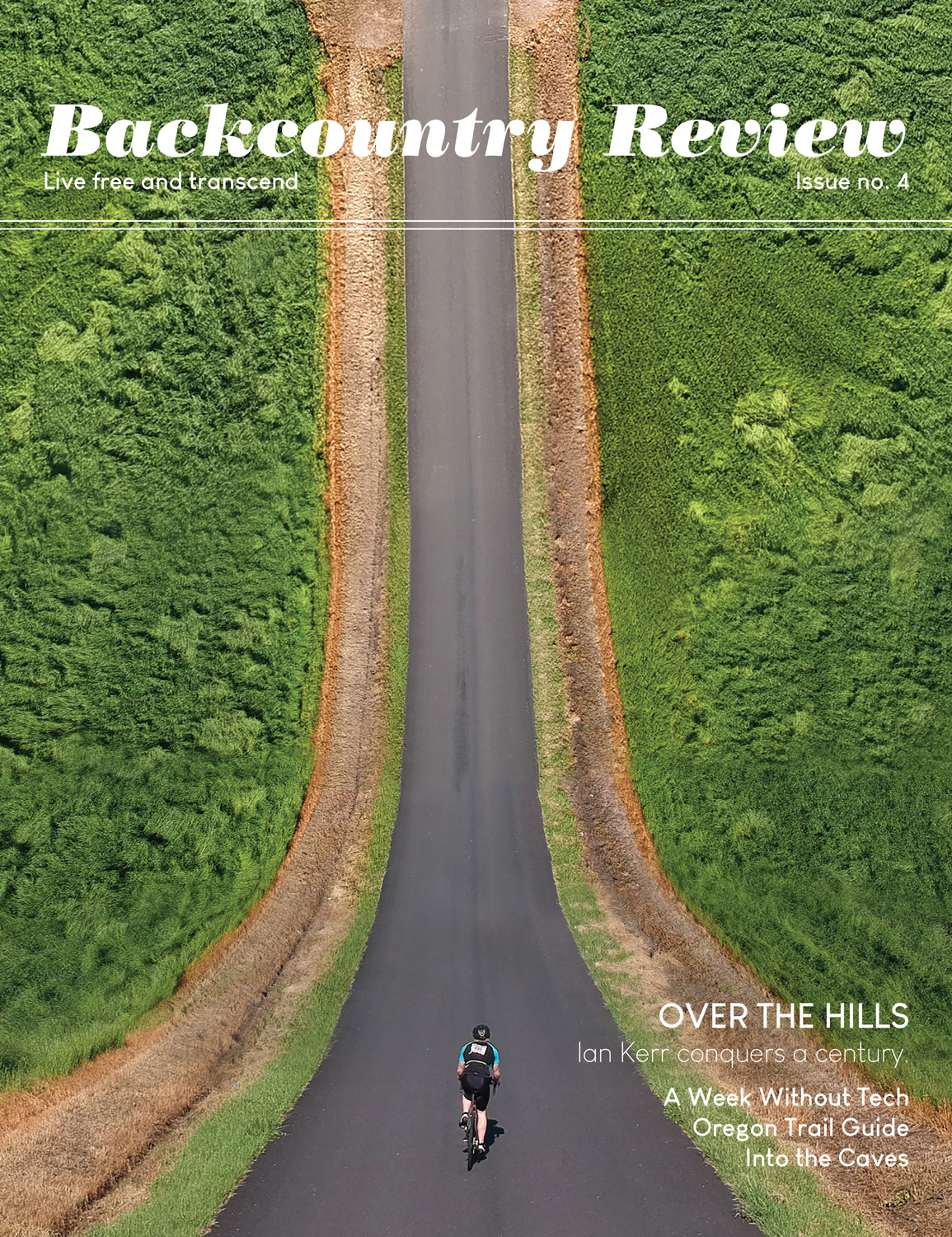

Apparently, reports of the death of print journalism have been a bit exaggerated — at least by the evidence of Miller’s class, where students do the hard but ultimately rewarding work of turning their wildly various experiences into a top-notch glossy magazine — one that, if we’re being honest, gives fellow glossy, Eugene Magazine, a run for its money and this weekly publication a double-take.

Started four years ago by Miller, the Miller Integrated Nature Experience (MINE) seeks to combine an appreciation of the outdoors with the act of writing, in the great naturalist tradition of American writers like Henry David Thoreau, Annie Dillard and Gary Snyder. The program’s mission, as stated on its Facebook page, is to “swap the classroom for the woods,” and to report back on that adventure with the tangible product of a student publication.

Needless to say, MINE is not your standard, standardized class of the familiar sort that begins with a desk-bound lecture and ends with a multiple-choice test, repeated ad nauseam. Nor, however, is MINE merely about looking at some plants and writing an essay. The scope of the program, along with the opportunities and challenges it presents for students, is staggering.

For instance, MINE’s most recent issue of its magazine, Backcountry Review, released just this past week, includes a feature story by senior Gabriel Cooper, in which he writes of flying himself and two classmates in a Cessna plane to Josephine County, where the trio went on a claustrophobic exploration of a ventilation shaft in the side of a mountain only to find the ceiling crawling with thousands of harvestmen spiders — indigenous, as they discovered, only to the Oregon Caves.

“In one day of skipping school and going on an adventure,” Cooper writes at the end of the article, “I became a better and more confident navigator, socialite, explorer, risk-taker, and most importantly, a stronger person, both physically and mentally.”

You gotta love that “skipping school” part, indicating as it does the urge for a deeper, more earnest education outside the walls of education.

This, then, is just one example of the expansive academics offered by MINE, which grants almost unlimited freedom to students as they explore their world and themselves, while also placing an inordinate burden of responsibility and accountability on their shoulders. Actions and consequences, responsibility and accountability: These are the real dynamics of adulthood, something for which no amount of standardized testing can account. It takes a village, indeed.

In a sense, the structure of MINE mirrors the path of Miller’s own transformation as a writer and educator. A Springfield native, Miller, now 37, studied at Loyola University in New Orleans. After he graduated in 2005, “I had no idea what I was going to do with my life, so I went on this road trip,” he says.

Then Hurricane Katrina hit. “I was really fired up with what happened with all the residents left behind,” he says of returning to the aftermath of the flooding, which devastated the city’s Ninth Ward. “I wanted to become a writer and change the world through writing.”

Miller’s pursuit of a writing career led him all over the place — Portland and Santa Fe — where he fell into various gigs, including working as a sportswriter. “Changing the world turned into sports writing,” he jokes. Eventually he was drawn back to his roots in the Northwest, returning to Eugene to be with his girlfriend.

Once here, he found himself working with young people. Along with Charlie Wilshire, he developed the backpacking program at Northwest Youth Corps (what is now Two Rivers Charter School), and coached basketball for North Eugene High School for a while. Then, six years ago, he ended up at Springfield High School, where he was an assistant basketball coach for three years.

Enlarge

He didn’t get the coaching job the next year, but he did get a position teaching English and journalism. “There was nothing,” he says of starting up the student publication back then. “It was rough, errors everywhere,” he adds. “It just kind of looked like nobody cared.”

But then he and his students decided to buckle down, and by the end of the year they had a pretty decent newspaper, winning a third-place award at a state student journalism competition. By the second year, he says, the “journalism thing really took off.” They put out the school’s first magazine.

In 2013, Miller pitched the idea of an outdoors program at Springfield High School, coupling it with his writing and journalism interests. By the end of the first semester, the program had landed a $2,000 innovative education grant from the Springfield Education Foundation as well as a $10,000 award from the Gray Family Foundation.

“It was through the roof,” Miller says of his students’ enthusiasm for the program. “They felt like anything was possible. By the end of that year, we’d done four big backpacking trips and put out a 48-page magazine. They just kind of crushed it. They did the impossible.”

Since then, MINE has partnered with a number of local organizations, including Northwest Youth Corps, the U.S. Forest Service, the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism and Communication, FOOD for Lane County, McKenzie River Trust and the Audubon Society, to name a few. “All of a sudden we had support,” Miller says.

Enlarge

“Every year it’s changed,” Miller says of MINE. “Each year these kids kind of set a new bar. It’s just incredible.”

It’s the interactive and collaborative nature of the program — combined with its built-in dynamic of fostering student autonomy and accountability — that really seems to attract students and push them to find the limits of their creativity. “There’s an increased sense of purpose and awareness of their environment,” he says. “We also have kids that feel connected to something bigger in the local community. It teaches people. It connects.”

“What kids really need is to feel a sense of community when they’re trying to figure out who they are in the world,” Miller says. “There’s plenty of research that says journalism education is good, that taking kids into the outdoors is good.”

The students in MINE, Miller adds, refer to themselves affectionately as “the Dirtbag Family,” a wry nod to the ecological and conservationist roots of their writing endeavors. He says that the idea is “not just go outside the box, but go outside.” And, while outside, to reflect on your experience in a way that can be expressed clearly and creatively.

“It just opens their eyes to a bigger world,” he explains. “With that comes the idea that there are possibilities for them to do the unthinkable.”

Having visited Miller’s classroom a handful of times, I can report that the effect of such “unthinkable” thinking is palpable and profound: The students are at once enthusiastic and intensely focused, exhibiting a rare professionalism and sophistication that speaks to the earnestness with which they regard their own work. It’s impressive, and incredibly inspiring, to behold.

And, make no mistake, what the students at Springfield High do is work. It’s not all fun and games in the woods. As much as the MINE program sparks their imaginations and engages their yen for nature, it also hones their skills through the real-life disciplines of looming deadlines and peer review. Miller’s class runs like any newspaper, staffed with designers, writers, photographers, copy editors and the like. The students learn on the fly, but they are very much in charge of the operation. It’s vocational in the truest sense of the word.

By choice and by design, Miller says he spends the preponderance of his class time running around answering questions and offering guidance rather than lecturing. “It’s amazing,” he says. “They really take on leadership roles. They embody everything they do.”

He says the evolution and growth of MINE over the past four years has opened his eyes to the value of a truly hands-on education where students have direct say in what they learn. Miller provides the barebones framework but, ultimately, the students fill it out with their sweat and talent. The test of their competency — the reward, the final grade — is the magazine they produce.

Enlarge

“It’s part of the difficulty, because it’s so outside the box right now,” Miller says of the unique nature of the program. “The model where you put the kids in charge and ask them what they want to learn and how they want to do it is different, but it’s really powerful. We can learn a lot from young people. They’re capable of incredible things if you give them the opportunity.”

Springfield senior Emma Babcock, 18, is one student who has seized the opportunities presented by MINE. Voted in by her peers as one of three chief editors this year, Babcock says she has grown into the leadership role she was given.

“I’m normally a very loud person,” Babcock says. “I try to command a classroom. I’ve learned to step back and accept what’s going on and be able to work with people, instead of standing on a chair and yelling at everyone. It’s cool to see that transformation,” she adds.

The recent issue of Backcountry Review contains Babcock’s profile of Clay River, a queer, non-binary Native American storyteller from Portland. One of the things she realized, in talking to River about how they (preferred pronoun) were treated in the media, is “how deceiving the media can be.”

Awareness of the power of journalism, its uses and abuses, is one of the lessons Babcock says she gleaned through her participation in MINE. “As a journalist, I have the power to tell the truth and the power to lie,” she says. “You can’t manipulate that power. It’s just dumbfounding how people take advantage of that.”

It could be argued that such hard-won media awareness in this media-saturated society — especially right now — provides a distinct advantage, not just in terms of knowledge but, perhaps, of survival itself. The old social-studies model of yore — names, dates, maps and moments — are inadequate in the face of a digital world that remakes itself by the second. Being a citizen now doesn’t mean what it did even 20 years ago, and students like Babcock (who starts at Salem’s Corban University this fall) appear better adjusted to the challenges of the online age, thanks to the rigors of MINE.

It would be wrong, however, to view the program as simply a training ground for future journalists, even if we need good ones now more than ever. It’s not even specifically about writing. The scope of the program — with its grounding in the outdoors and its goals of personal expression and team collaboration — is broad enough to capture the interests of all kinds of students, and to bring them together in pursuit of a common goal.

In this sense, it has an existential value, for lack of a better term — a value that radically re-envisions what, exactly, an education should entail, and one that challenges our current bureaucratic tendencies toward grinding the kids into pliable consumers.

“I feel like for the first time in high school I’ve actually had the ability to be really creative,” says senior Ben Walsh, whose work on Backcountry Review involved “mostly design stuff,” he says. “The writing hasn’t really inspired me much,” he continues. “I actually was surprised when they picked me as a designer. I never even knew InDesign was a thing before,” he adds, referring to a popular design platform (Eugene Weekly uses it).

What Walsh lacked in experience, he made up for in enthusiasm, “going all-out on everything I could for the newspaper” and educating himself on the ins and outs of design: photos, layout, type, synchronized spreads. “I feel like for the first time in high school I’ve actually had the ability to be really creative,” he says, adding that his experience in MINE inspired him to pursue a degree in mechanical engineering at Oregon State University, on a Ford Family full-ride scholarship, no less.

“It’s done a lot for my mental health,” he says. “Career-wise, it’s put me in the right direction. This class has definitely shown me that everything is connected,” he adds, referring to the collaborative effort of assembling multiple elements to put a single article together, from writing and editing to making it look good on the page. “You have that connection with the piece when you design it.”

Darrel Harrison, a senior who will be heading to Lane Community College next year, also found his calling as a creative director in MINE. As a kid, Harrison remembers “messing around” with photo applications on his computer, matching pictures to text, and when he entered high school he found himself increasingly interested in artsy projects, including designing event posters for the theater and band departments. From there, it seemed a logical leap to working on student publications.

“With the entire design aspect, I feel like I’ve put myself in a different atmosphere,” Harrison says of working on Backcountry Review. “Collaboration is key. That’s the big thing I learned here, that it’s not just a solo job. It’s all about the group,” he adds.

“It’s been quite an experience,” he says of finishing up the most recent edition of Backcountry Review. “I’m really satisfied with what we did.”

Miller suggests that it is being part of something bigger than themselves — the magazine, the community, the world at large — that also allows each student to explore his or her own identity, and to see where they fit in the world in a process of reckoning, individuality and belonging. If this isn’t the goal of all education, it should be.

“That’s the most surprising part,” Miller says of observing the change that takes place in his students. “Once I started taking kids on these bigger trips, I started seeing these transformative experiences taking place. These kids found meaning in their lives.”

This fact hit him hard last year, during a trip with students to The Lodge at Summer Lake in Oregon’s high desert. Sitting in the lodge or around the campfire, he says, the kids eventually started “pouring their hearts out, expressing themselves.” Traumatic experiences were recalled, one student came out of the closet, and a kind of group healing took place — a healing that seems unlikely in the staid confines of a high school classroom.

“All of a sudden it felt so much bigger than taking kids on hikes,” Miller says. “They found meaning because of what we were doing.”

A Note From the Publisher

Dear Readers,

The last two years have been some of the hardest in Eugene Weekly’s 43 years. There were moments when keeping the paper alive felt uncertain. And yet, here we are — still publishing, still investigating, still showing up every week.

That’s because of you!

Not just because of financial support (though that matters enormously), but because of the emails, notes, conversations, encouragement and ideas you shared along the way. You reminded us why this paper exists and who it’s for.

Listening to readers has always been at the heart of Eugene Weekly. This year, that meant launching our popular weekly Activist Alert column, after many of you told us there was no single, reliable place to find information about rallies, meetings and ways to get involved. You asked. We responded.

We’ve also continued to deepen the coverage that sets Eugene Weekly apart, including our in-depth reporting on local real estate development through Bricks & Mortar — digging into what’s being built, who’s behind it and how those decisions shape our community.

And, of course, we’ve continued to bring you the stories and features many of you depend on: investigations and local government reporting, arts and culture coverage, sudoku and crossword puzzles, Savage Love, and our extensive community events calendar. We feature award-winning stories by University of Oregon student reporters getting real world journalism experience. All free. In print and online.

None of this happens by accident. It happens because readers step up and say: this matters.

As we head into a new year, please consider supporting Eugene Weekly if you’re able. Every dollar helps keep us digging, questioning, celebrating — and yes, occasionally annoying exactly the right people. We consider that a public service.

Thank you for standing with us!

Publisher

Eugene Weekly

P.S. If you’d like to talk about supporting EW, I’d love to hear from you!

jody@eugeneweekly.com

(541) 484-0519