The dusty cassettes were about to be thrown away. Sometime back in the ’80s or early ’90s, they’d been consigned to longtime Eugene record store House of Records. The store was cleaning out old merchandise, so they were just about to get rid of them.

So around 2011, Douglas Mcgowan, a Eugene resident at the time and frequent customer at House of Records, asked if he could have them.

“There were three Heather Perkins tapes,” he tells me over the phone. “I thought she was really extraordinary.”

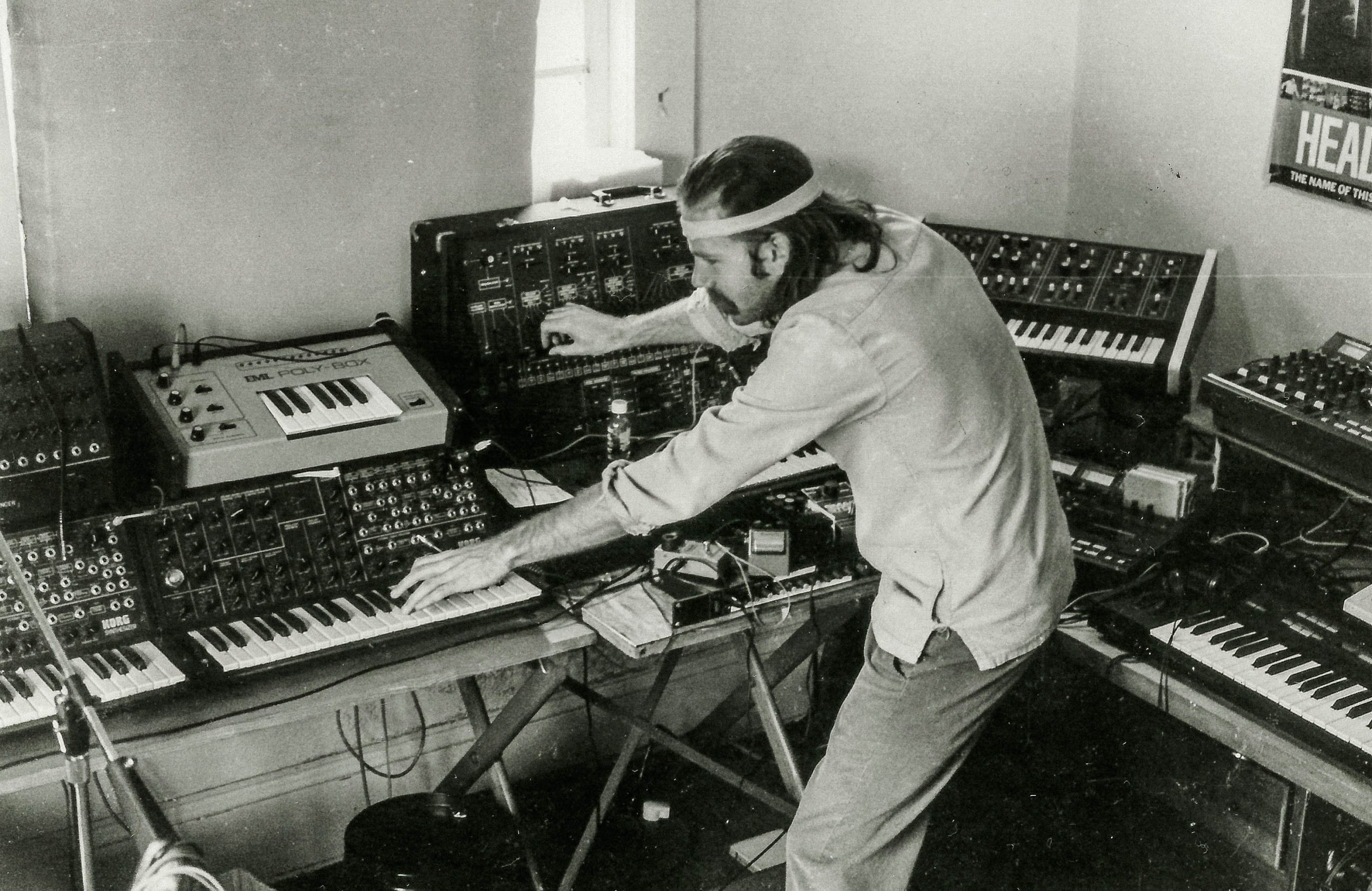

Enlarge

courtesy of Gwendelara Hendee

The tapes were produced by the Eugene Electronic Music Collective, and this discovery led Mcgowan to seek out founding members of the EEMC.

“There was this secret history,” he says.

Active for about a decade between the mid-’80s and mid-’90s, EEMC was relatively well known in the electronic music production and tape trading scene of the era. But before Mcgowan discovered the tapes, the story of EEMC had been largely lost.

The group shared synthesizers as well a recording equipment while collaborating on one another’s music. They also took turns handling the business end, acting as a sort of record label and music distributor for work from within the collective and elsewhere.

Composer and guitarist Peter Thomas is the only founding member of EEMC still in Eugene. “There was something about the electronic sound that I really liked,” he says.

We’re having coffee on a warm fall afternoon at Noisette in downtown Eugene. Thomas’ beard and shaggy hair are both white now. His smile is warm and wide, and he still wears his Devo T-shirt.

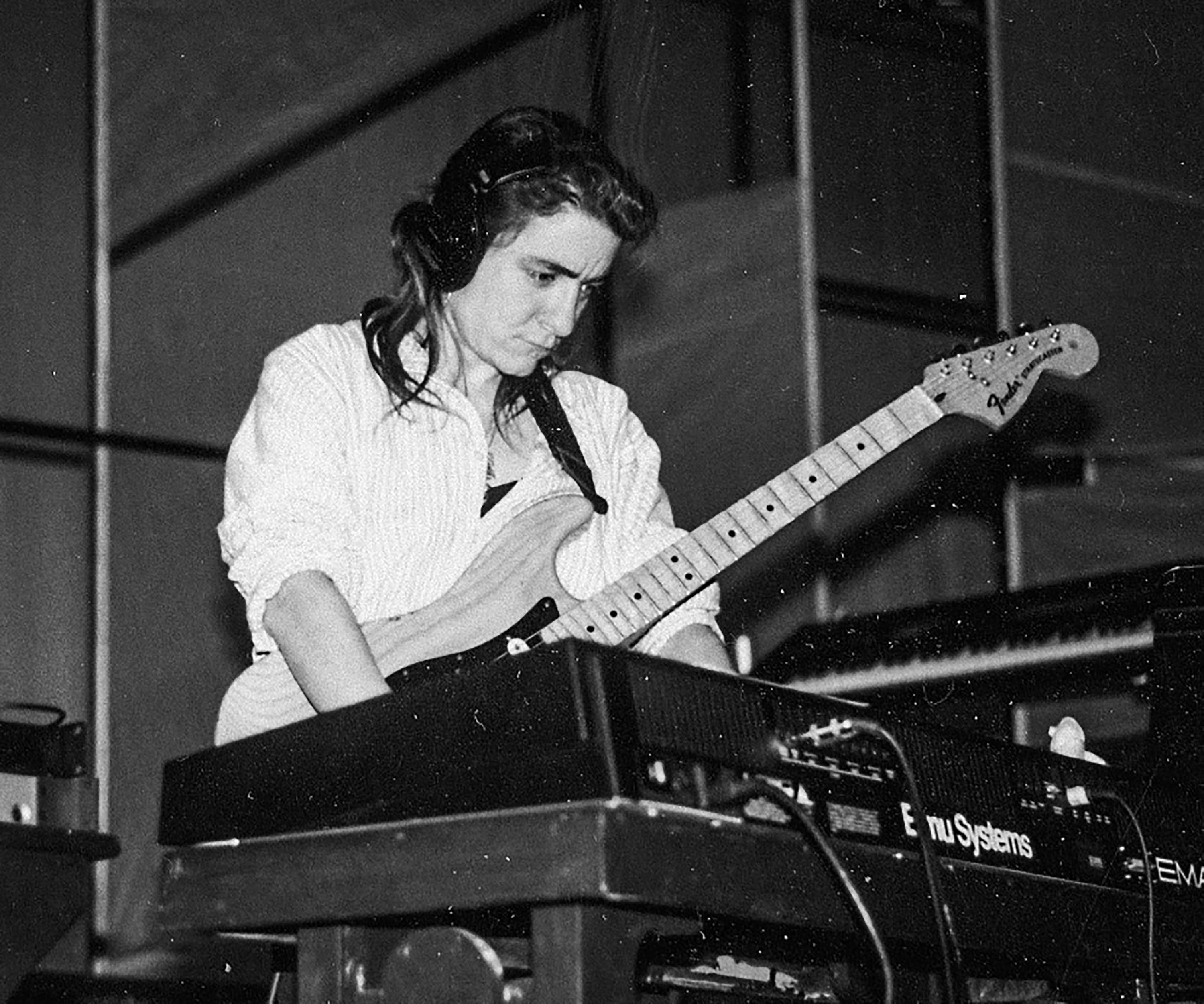

Enlarge

Photo by Athena Delene

“I liked the tone colors,” he says. “The sounds they could make. You could tell from the tone colors these synthesizers can do some really cool things.” Thomas was familiar with classical orchestral music from his classical guitar background. “I knew what a good orchestra could do,” he adds.

“Most of my pieces started off as improvisations,” he goes on. “I would be playing something on a synthesizer and go, ‘Oh, that’s pretty good.’ I should save that.”

EEMC placed ads for new releases in electronic music-themed zines and magazines, produced promotional material and fulfilled mail orders. EEMC founding member Peter Nothnagle started KLCC’s New Dreamers, an electronic, ambient and new age radio show.

While Nothnagle has moved out of the area, New Dreamers is still on the air.

“The collective was the label,” Thomas explains. Musicians shared a mailbox. “All the orders came in through that.”

Someone would check the orders and “that was how we did stuff.” One person might take care of the mail. Another person might do the mastering of the recordings and another person did the artwork.

“It did seem to catch on,” Thomas says of EEMC’s niche success at the time. Not only zines but also full-scale magazines were devoted to DIY electronic music. “We advertised our collective compilations,” he says. “We sent them copies for reviews.”

Around Eugene at the time, the collective mentality was just in the air, Thomas says.

After taking a job as a producer at esteemed archival record label Numero Group, Mcgowan, who no longer lives in Eugene, pitched to the label Switched On: Eugene, a compilation of releases from the Eugene Electronic Music Collective. The project took about three years to complete.

Numero Group is known for uncovering lost and dusty musical treasures from overlooked and underappreciated regions of the world. “This is exceptional in the sense that it’s a very clear-cut example of a thing: the ways in which things happened before the internet,” Mcgowan recalls of his initial pitch to the record company.

“That’s what fascinated me about it,” Mcgowan continues. “Which is something people my age tend to be somewhat aware of, but young people might not be aware of.” People had to find creative ways to share information with each other, he says. “They were using the cassette, which was the most democratic medium for sound before MP3 came along. They were using zines. They were using radio shows. They were approaching everything with a spirit of openness.”

Switched On: Eugene covers a lot of ground, from ambient to new age, and from krautrock to new wave and pop. You’ll hear tones of Brian Eno, Vangelis, Can, Devo and Laurie Anderson.

Enlarge

courtesy of the artist

While some of the material is hard to grab on to before it disappears in a puff of air, other tunes, like “The Ride” by Jill Talve’ or “Patterns” by Suse Milleman, are relatively pop-oriented.

“The Seven Rays” by David Stout even has some of the space-aliens-come-to-Earth quality of early Devo, alongside, of course, a healthy dose of hippie mysticism.

The release is beautifully packaged, featuring illustrations from the late Eugene artist Paul Ollswang, who died in 1996. He was “sort of the Robert Crumb of Eugene,” Mcgowan says.

EEMC’s didn’t last forever. By the early ’90s, the electronic music scene had changed, and the collective drifted apart.

“It lasted almost a decade,” Mcgowan says. The internet was starting, and MIDI technology was permanently changing the nature of synthesized music.

“When we were first starting,” Thomas says, “not that many people had synthesizers. By the ’90s the whole thing had exploded. The whole thing changed and it lost some momentum.”

Every artist toiling in obscurity dreams of one day receiving the kind of phone call Thomas got from Mcgowan — that phone call saying, I’ve discovered your work and I want to share it with the world.

“I had no idea who Doug Mcgowan was,” Thomas says.

“You were part of this thing called the EEMC?” Mcgowan asked him. “I’d really like to meet you.”

“How did this guy find me?” Thomas thought.

Every artist has that phone call in the back of his head, Thomas says. “Somehow it happened to me.”

Switched On: Eugene is available on most music streaming services and on double-LP and CD wherever music is sold.