When Charles Dalton came to Eugene about 50 years ago as a spokesperson for the NAACP, he went downtown to get to know the area. He explains in a video on display at the University of Oregon’s Museum of Natural and Cultural History’s new exhibit — “Racing to Change: Oregon’s Civil Rights Years, the Eugene Story” — that “a Black hippie” asked him for a cigarette. Next thing he knew he was being questioned by police.

Great, he thought: In Eugene about a half an hour and already stopped by the police. Then he discovered the Eugene Police Department kept a book with pictures of African Americans who stayed in the city longer than a week, and that his picture was in it.

Later, in his role as NAACP spokesperson, he had an opportunity at a public event to question the existence of the book. A Register-Guard reporter heard and then shortly after asked the chief of police about the book. The chief responded that the book was no longer in use.

Dalton considers the change a “minor victory” but classifies himself as an optimist. “We’re not where we want to be. We’re not where we’ve been,” he says. But, he adds, “We’re going in the right general direction.”

Dalton’s video history, and videos of other community members, bring to life the written matter and materials on display in “Racing to Change,” personalizing experiences that reflect the larger attitude held by mainstream culture towards African Americans in Eugene in the 1960s and ’70s.

The exhibit runs through May 10 and was co-created by the organization Oregon Black Pioneers. Its grand opening was Oct. 12 — also the opening of the UO’s Lyllye Reynolds-Parker Black Cultural Center.

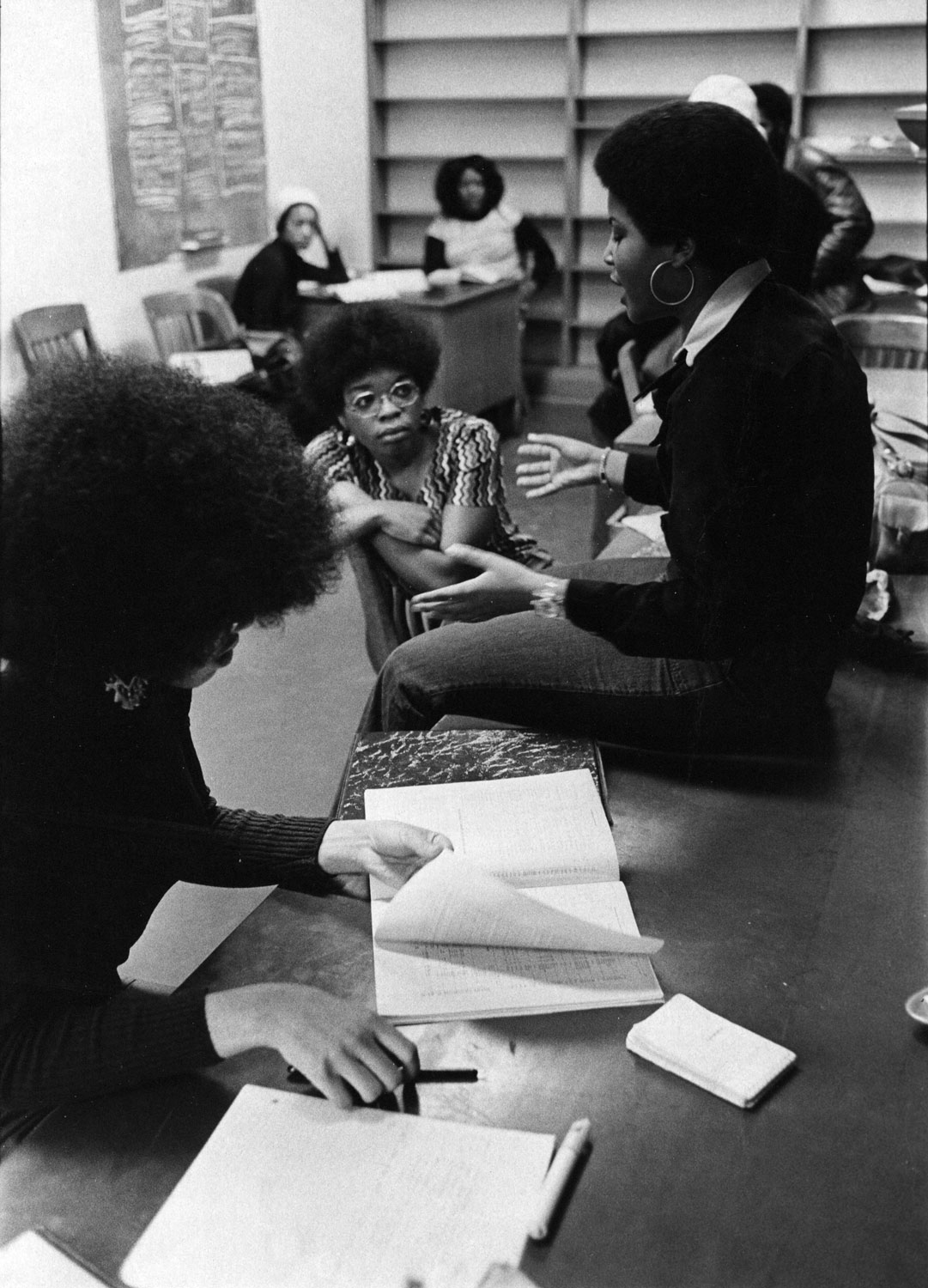

Enlarge

Image courtesy Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries

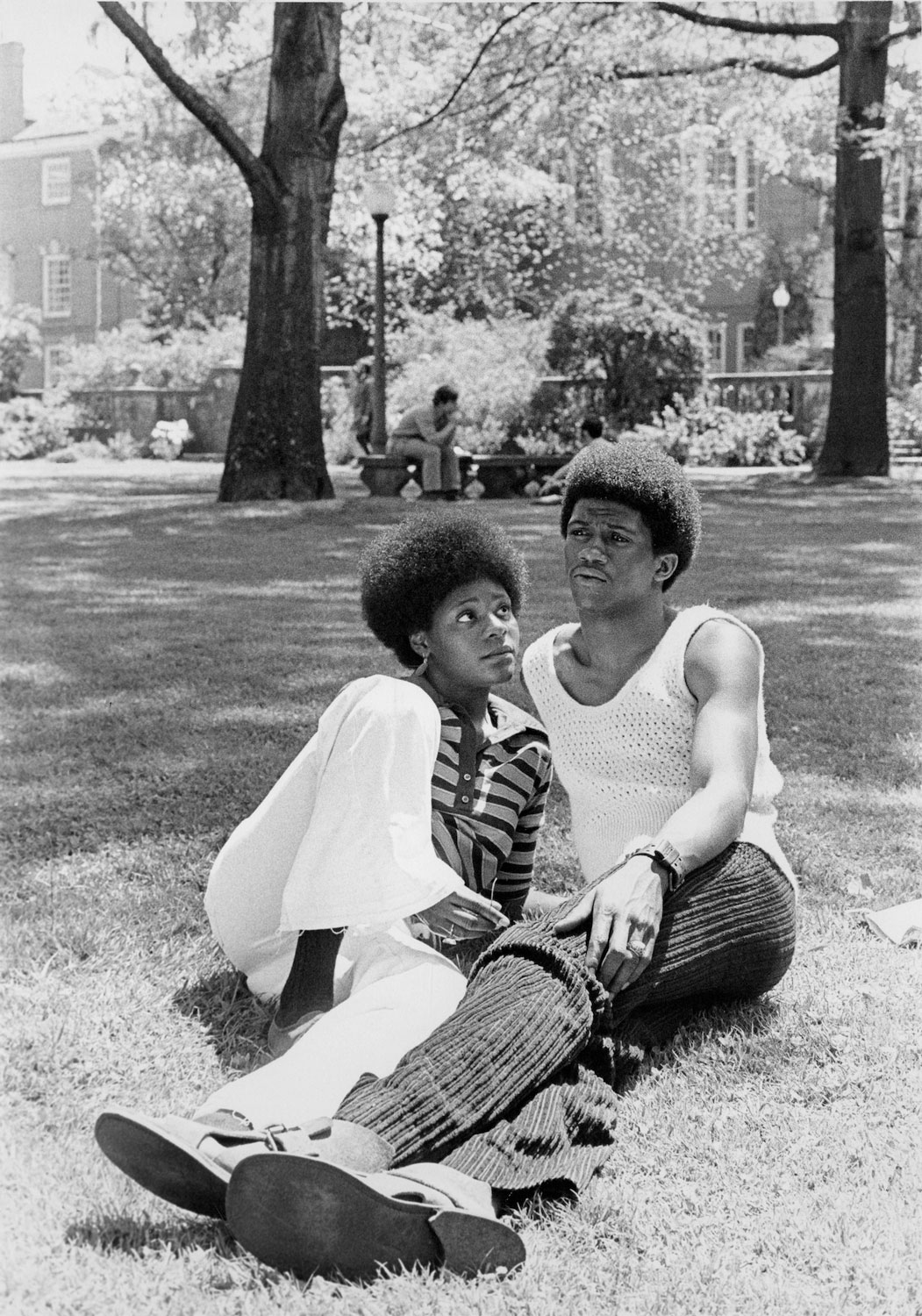

What makes this exhibit particularly fascinating is its focus on Eugene. It’s not a grand exhibit about racism in America or even in Oregon. This is us, our town. Amid the testimonies and history is a small display that reads, “Many of the people in photographs we have from the 1960s and 70s are unnamed. Do you recognize anyone? Let us know!”

The opening ceremony featured the gospel group Powerhouse Praise Team. They sang, among other songs, “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ’Round”:

…I’m gonna keep on walkin’

Keep on talkin’

Marching into freedom land.

Following the singers, state Sen. James Manning Jr. joked that the music made him feel as if he was coming up to the pulpit. He spoke about being restricted as a kid in St. Louis, Missouri, in terms of where he was able to set foot. He agreed with museum exhibit director Ann Craig, who also spoke, about the importance of museums.

“Education is our greatest social equalizer,” he said.

With only 10 minutes for his speech, he didn’t step down until he made another joke, this one more pointed. After acknowledging the presence of UO President Michael Schill, Manning said wouldn’t it be great if the university built a museum as grand as Autzen Stadium or the university’s new track and field venue currently under construction?

State Rep. Julie Fahey also attended the reception. She contributed materials to the exhibit related to her sponsorship of a new bill. When she discovered the property deed to her house stated it could only be bought by “members of the Caucasian race,” she sponsored House Bill 4134. Signed into law in 2018, the bill makes it easier for homeowners to remove racist language.

“Racing to Change” points out that discrimination hasn’t always been codified or formal. One of Eugene’s earliest African American residents, Willie C. Mims, is cited: “There was not a bank in this whole city that would lend a Black man money for a business.”

And a 1962 edition of Green Book: A Guide For Travel and Vacations provides evidence that restricting Blacks was an unspoken tradition in the days before the civil rights movement. The “guide for travel” lists lodging, restaurants and gas stations that would serve Black customers. Only 10 hotels in Oregon were listed in the 1962 Green Book.

Enlarge

Image courtesy Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries

When Oregon Black Pioneers’ President Willie Richardson spoke to the crowd, she said that though history is sometimes ugly it needs to be acknowledged. She made a point that looking at the ugly truth was not an exercise in blaming, but rather a necessary step towards moving forward.

In 1968 the relatively new Black Student Union at the UO issued a list of demands. Among them was “that office space and adequate facilities be provided to the Black Student Union in order to conduct a study skills and tutoring center.” That 1968 list is on display in the exhibit beside a 2015 list that puts forth a similar demand: to “fund and open a Black Cultural Center.”

The newly opened Lyllye Reynolds-Parker Black Cultural Center sheds light on a major theme in the exhibit: We are still on this journey. It is one we must make together across subcultures as Americans. As Charles Dalton put it, “two steps backwards, one step forward.” Exhibits such as this help to educate and engage, to keep us moving in the right general direction.

Help keep truly independent

local news alive!

As the year wraps up, we’re reminded — again — that independent local news doesn’t just magically appear. It exists because this community insists on having a watchdog, a megaphone and occasionally a thorn in someone’s side.

Over the past two years, you helped us regroup and get back to doing what we do best: reporting with heart, backbone, and zero corporate nonsense.

If you want to keep Eugene Weekly free and fearless… this is the moment.