Plenty of people, at least in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, have heard of the William L. Finley National Wildlife Refuge a little south of Corvallis. But very few people know anything at all about William L. Finley, the remarkable early 20th-century conservationist and photographer for whom it was named.

Eugene historian Joe R. Blakely is seeking to close that information gap with his latest book, William Lovell Finley: Champion of Oregon’s Wildlife Refuges, which Blakeley published himself this spring. In it he details not just Finley’s persistence in creating or saving wildlife refuges in Oregon and California but many lesser known and equally fascinating chapters in Finley’s unusual life.

Born in northern California in 1876, Finley lived at a time when much of Oregon was wilderness, and conservation was a novel concept that was just beginning to gain traction both here and nationally. By the time his family moved to Portland in 1887, the young Finley had developed an abiding interest in birds — an interest he shared with a slightly older neighbor boy, Herman Bohlman, with whom he would become friends and later partners in conservation work and photography.

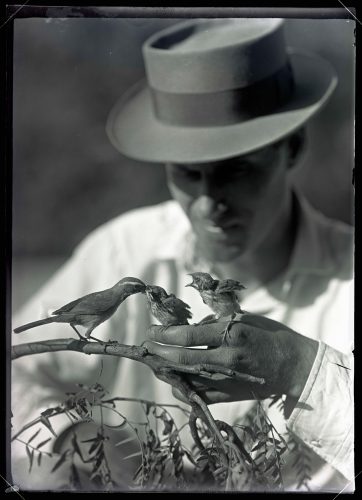

As teenagers the two of them collected and sold bird eggs and skins, popular with collectors of the day, but by the end of the century the pair had begun instead to take photographs of birds, eventually hauling their bulky equipment high into trees — Finley and Bohlman photographed eagles at their nest 70 feet up in a sycamore — and scaled sheer cliffs to get close to their subjects. It was Bohlman who first began to explore the photography equipment of the day — bulky, heavy, large-format cameras that used fragile glass plates in place of film, a process more suited to formal studio portraits of unmoving people than capturing photographs of small, active birds.

When he went off to study history and philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1900, Finley began writing articles for the nature magazine The Condor and joined the Cooper Ornithological Club.

Blakely tells all this and more in his 200-page book, which is full of Finley and Bohlman’s highly detailed photographs. He describes such long-forgotten episodes as Finley’s decision, as Oregon’s first game warden, to replenish hunted-out populations of elk in the northeast corner of the state. To do this he shipped 23 elk by wagon train and railroad through spring snow from Jackson, Wyoming, and turned them loose in Oregon’s Blue Mountains in a production that drew large crowds who turned out to see the elk along the way.

He also, as described in one quirky section of the book, kidnapped a California condor chick he had been photographing in the wild in southern California in 1906 and brought it home to Portland, where he hand-raised it to maturity — it’s as “playful as a pup,” he once wrote — before sending it to the New York Zoological Park, where it lived for years.

The grand finale of Blakely’s book is the chapter on Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in eastern Oregon. Though the refuge had been established in 1908, it lacked water rights, and the enormous marshes and lakes that once served as home for millions of birds were drying up in the 1920s and ’30s. Finley helped lead a massive political fight that involved two Supreme Court decisions and a personal visit to the White House to bring back the water and make the refuge useful for wildlife again by 1936, declining along the way a bid to rename the refuge in his own honor.

Joe R. Blakely’s William Lovell Finley: Champion of Oregon’s Wildlife Refuges is available for $17.95 at J. Michaels Books and Tsunami Books in Eugene. On Memorial Day weekend, weather permitting, you can buy copies between noon and 2:30 pm Sunday, May 30, and Monday, May 31, next to the display pond by the visitor center at Finley National Wildlife Refuge, off Highway 99W 10 miles south of Corvallis. The address is 26208 Finley Refuge Road, Corvallis. Cash and checks only, no credit cards. Sales benefit Friends of the Willamette Valley National Wildlife Refuge Complex.