By Garrett Epps

Former Oregon Secretary of State Shemia Fagan left office in disrepute, but on one important occasion she did her job well. Her successor, LaVonne Griffin-Valade, will need to do the same — under conditions far more stressful than those Fagan faced.

In the fall of 2022, New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof was generating buzz as an outsider candidate for governor. A Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, Kristof looked like an exciting new force on the political scene.

But officials in the Elections Division concluded that he did not meet the Oregon Constitution’s requirement of three years’ residency before a gubernatorial election.

Kristof was outraged, telling Twitter followers that “A failing political establishment in Oregon has chosen to protect itself, rather than give voters a choice.” The Oregon Supreme Court, however, ruled unanimously that Fagan had acted correctly. She emerged from the conflict looking better than her detractors.

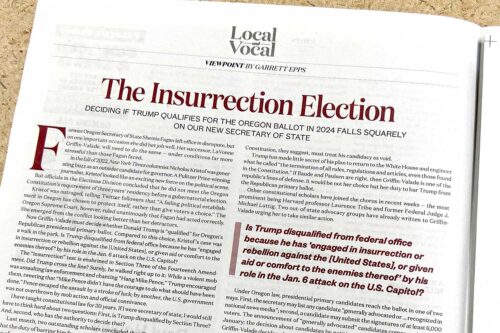

Now Griffin-Valade must decide whether Donald Trump is “qualified” for Oregon’s Republican presidential primary ballot. Compared to this choice, Kristof’s case was a walk in the park. Is Trump disqualified from federal office because he has “engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the [United States], or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof” by his role in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol?

The “insurrection” test is enshrined in Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment. Did Trump cross the line? Surely, he walked right up to it: While a violent mob was assaulting law enforcement and chanting “Hang Mike Pence,” Trump encouraged them, tweeting that “Mike Pence didn’t have the courage to do what should have been done.” Pence escaped the assault by a stroke of luck; by another, the U.S. government was not overthrown by mob action and official connivance.

I have taught constitutional law for 30 years. If I were secretary of state, I would still have to think hard about two questions: First, is Trump disqualified by Section Three? And, second, who has the authority to decide that?

Last month, two outstanding scholars concluded that Trump is disqualified, and that the duty of barring him from office falls to, among others, America’s 51 secretaries of state. William Baude of the University of Chicago and Michael Stokes Paulsen of the University of St. Thomas, staunch conservatives and adornments of the Federalist Society, published a paper, “The Scope and Force of Section Three,” laying out the history behind that conclusion. They contend that Section Three applies to Trump’s actions on Jan. 6, and that his disqualification is “self-executing”— it doesn’t require a conviction, court action or legislative vote. As of Jan. 7, 2021, they argue, Trump simply has been ineligible to serve as president. Any official who has sworn to support the Constitution, they suggest, must treat his candidacy as void.

Trump has made little secret of his plan to return to the White House and engineer what he called “the termination of all rules, regulations and articles, even those found in the Constitution.” If Baude and Paulsen are right, then Griffin-Valade is one of the republic’s lines of defense. It would be not her choice but her duty to bar Trump from the Republican primary ballot.

Other constitutional scholars have joined the chorus in recent weeks — the most prominent being Harvard professor Laurence Tribe and former Federal Judge J. Michael Luttig. Two out-of-state advocacy groups have already written to Griffin-Valade urging her to take similar action.

Under Oregon law, presidential primary candidates reach the ballot in one of two ways. First, the secretary may list any candidate “generally advocated or … recognized in national news media”; second, a candidate may submit the signatures of at least 6,000 voters. The announcement of “generally advocated” candidates comes at the end of January; the decision about candidates by petition takes place in March. Whatever Griffin-Valade decides, the question is all but certain to end up in court.

She will face partisan blowback and even potential danger either way. We as citizens are entitled to send her our views, but we are not entitled to demand that she decide the issue one way or the other; fulfilling an oath is a matter for a detailed legal opinion in the first instance and, in the second, the individual conscience of the official. But what we should expect is that her office will make the decision with the same dispassion, care and scorn for partisanship that Fagan showed when she blocked the popular Kristof in 2022. ν