Marina Herrera mixes compost and soil to replant her tomatoes. The stems look as if they were strands of spaghetti noodles that could fall down anytime — Herrera had been growing them at her apartment, where the sun comes in only in the afternoon. They grew tall but with thin, light green stems.

“I hope they grow stronger with this sun,” Herrera says as she places the tomato branches to the new soil gently with her hands.

Gardening work is perfect when the sun clears out the sky, and the contrast of green and pure blue paints your vision. Herrera has joined 15 people at the Skinner Butte Community Garden Spring Cleaning Work party. Some speak Spanish, others English or a mix of both.

People in the garden often are part of immigrant communities and diasporas, and each has a section of the garden to plant.

Plaza de Nuestra Comunidad organizes seven different community gardens in Lane County, including the one where Herrera has her slot. Community members can reach out to the organization, and gardens will be assigned, or they will be put on a waiting list.

Plaza is a nonprofit founded in 2021 after three organizations — Centro Latino Americano, Downtown Languages and Huerto de la Familia — joined together to provide support for the immigrant and diaspora community. It provides various types of support, such as language courses, mental health support and organic garden programs for the community.

“Fear is the hardest thing right now with unknown things,” says Abigail Molina, a founding attorney at Molina Law Group. She says the government and media tend to publicize small things such as crime or drug lords and make them big, which brings additional fear and threat.

She focuses on immigration law. She also says that there are misunderstandings and misinformation about how to access help and who is eligible for it. Organizations such as Plaza and immigration law services have seen more community members reaching out in the last few months since President Donald Trump came into office.

The Trump administration has been vocal about its stance on immigrants and immigration policies. News about immigrants being deported struck the attention and fear of many in the community. In Lane County, about 10 percent of the population is from Hispanic and Latino communities, although their voices seem to be quieter compared to other cities or states.

“Many are afraid to even take buses or walk around,” says Gatlin Fasone Alshuyukh, the organic garden program manager at Plaza de Nuestra Comunidad.

“I think that spaces like this, where folks can come together and grow their culturally important foods and speak their language, interact with their neighbors and belong to a space, are very important,” she says.

•••

Fig trees lining the edge of the garden sag with ripening fruit. Rows of black beans, yellow and green peppers, onions and garlic run through the garden.

Herrera grows what she likes, such as peppers, rosemary, garlic and more.

She was born in New York, and soon after, she and her family moved back to Guatemala, where she grew up being passionate about archeology, art and farming. (At that time, Guatemala did not allow dual citizenship, so she ended up choosing U.S. citizenship.) When Herrera moved to Eugene in 2007, it was a rough transition — she lost her son due to an accident, and she got divorced from her husband. She had a daughter to take care of and took multiple different jobs to support her family. She distanced herself from her artistic work.

Now her daughter just graduated from college — she is the only relative in the U.S.; the rest are in Guatemala.

Herrera’s daughter once told her, “Mama, I realized that if I want children, I need to have children soon so they can get to know you.”

“I want to be healthy, and if my daughter has a child, I want to be able to take care of her baby,” Herrera says, working on her farm under the sharp sun hitting her arms.

Herrera hopes to move back to Guatemala, where she feels at home, and she hopes to live there and visit her daughter in the U.S.

“Tell you the truth, I never thought that I would come to the U.S. to live,” she says.

She did not know any English when she first moved to Birmingham, Alabama, in her early 20s with her then-husband. Through someone they knew, she found a job at a bakery, and she learned English through those conversations with customers and learning all the names of bread.

Herrera still remembers an interaction with a customer almost three decades ago.

“Where did you come from?” one customer asked Herrera.

“Guatemala,” she answered.

“No, I’m not asking for your name; where are you coming from?” the customer asked again.

“Guatemala is my country that I am from.” Herrera answered, realizing that the customer clearly did not know about her home country.

Herrera says that there were moments when she felt the keen lack of knowledge of Latin America among Americans when she first came to the U.S. At the time, she did not see other Latin Americans in town and felt isolated. She then met some international students from a college nearby and felt a sense of community and togetherness.

•••

It was getting close to noon at the garden work party. Alshuyukh walked her six-month-old son around the garden.

“Tell everybody to go that way,” Alshuyukh says to another volunteer, pointing towards the tents with a picnic lunch.

“Es la hora del almuerzo,” Alshuyukh tells some Spanish-speaking community members.

“Vamos, vamos!”

When they gather, Alshuyukh assists them in making a circle.

“Let’s introduce ourselves — your name, why you are here, and what do you like about this community?”

Following this instruction, Alshuyukh speaks in Spanish, making this space fully bilingual. Alshuyukh helps translate the introduction in both languages.

Alshuyukh didn’t grow up speaking Spanish but learned it through school and her effort to speak it fluently. Some of her loved ones and friends speak Spanish, which inspired her to practice the language more.

“The speech and the way people are talking about immigrants are hateful and scary,” she says, and it further inspires her to work in a space where people can come together and feel connected through culturally important foods and speak in their language.

One of her goals for these organized events is to create opportunities for the community members to meet and make connections with one another.

“It makes it a more resilient and connected community,” she says.

Organizations like Plaza de Nuestra Comunidad and immigration attorney Molina suggest and assist people to fill out preparation packages to secure options for their children in case of crisis situations.

•••

Herrera now works as a medical interpreter, helping many patients from immigrant communities to overcome the language barrier in the medical field.

Herrera speaks not only both Spanish and English to people, but she also talks to the plants — “I think I talk with plants because my grandmother did it, too, you know,” she says with a laugh.

Herrera visits her garden two or three times a week to water, plant new things or just to check in on her garden.

In the late afternoon, a man walks into the garden with a smile on his face, and Herrera greets him in Spanish.

Frank Romero also has a section in the garden, growing beans and other vegetables. He is from El Salvador and immigrated to Canada due to the political conditions in El Salvador, then came to Eugene.

“She made art about me,” Romero said.

Art had been Herrera’s passion since she was young. She had been involved with the art and the art community in Guatemala, Alabama and California, where she has lived.

And now, she has begun to connect with the community through art again.

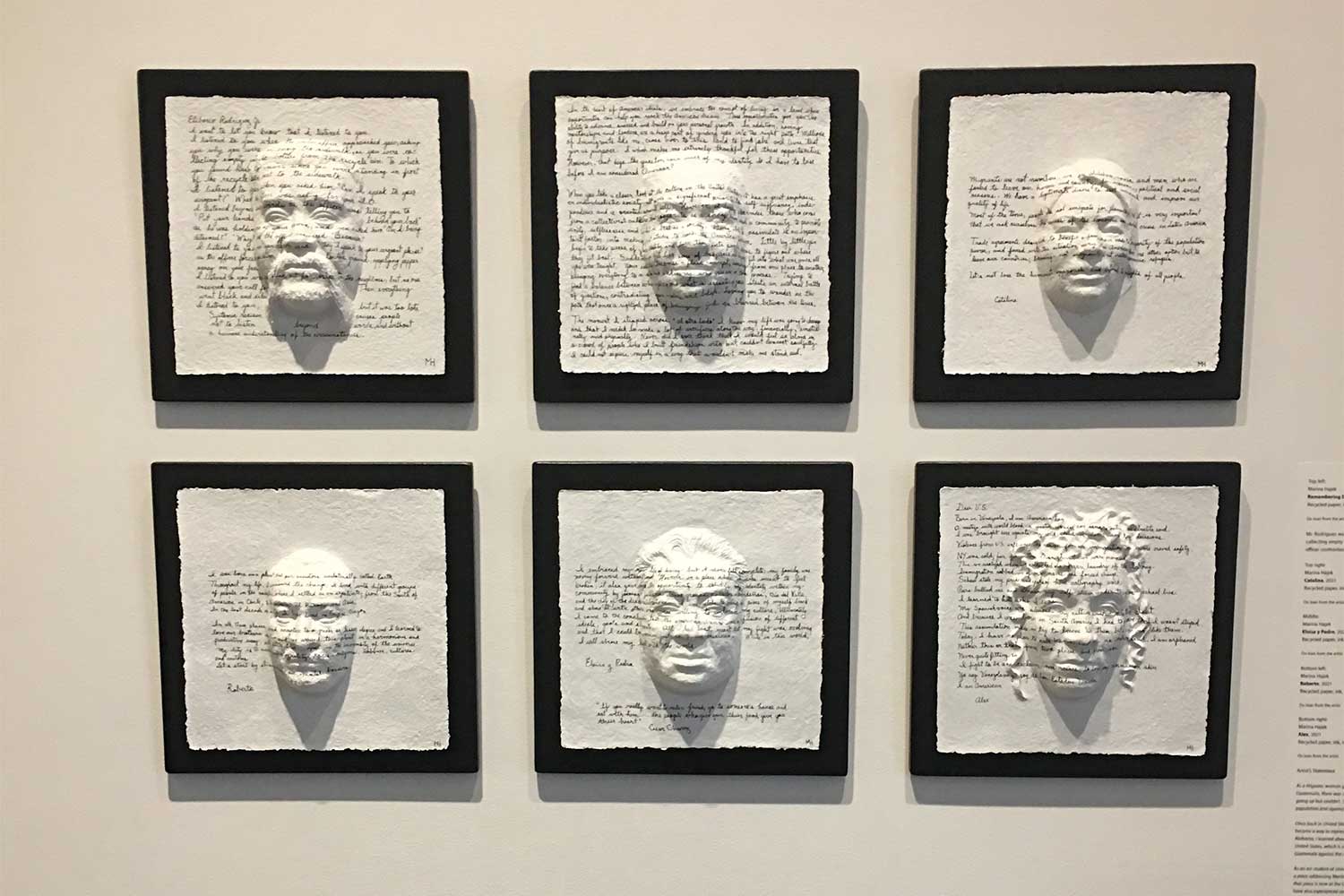

One of Herrera’s latest works is inspired by the stories of immigrants and diasporas. She has sculpted faces of immigrants — some are from the community garden — and the faces are overwritten with letters by immigrants on them so it looks as if the faces are talking.

“I want to teach Americans where we are coming from,” Herrera says. “Not everybody is a drug lord.” She says that negative news tends to define the image of the Latin American community.

“I want to share that this is us, too,” Herrera says.

She plans to showcase her art at the Palace Coffee and Bakery on Pearl Street in the fall, aiming to foster community engagement through the artwork.

Three weeks after the work party, the tomato starts Herrera planted turn into green, strong plants that are about to bear some tomatoes.

Strong with sunshine, good soil and a good environment — like us humans, they need positivity over fear, good resources and a safe environment in which we can thrive.

You can find resources by visiting Plaza’s website at PlazaComunidad.org/resources. The organization provides mental health, education and youth development, social services and recovery services in addition to the organic garden program led by Gatlin Fasone Alshuyukh. You can donate online at PlazaComunidad.org/support/donate to support the cause. This story received support from the Local News Initiative at the Catalyst Journalism Project, based at the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication. For more, see CatalystJournalism.uoregon.edu. Seira Kitagawa is an intern in the Charles Snowden Program for Excellence in Journalism.