By Kim Kelly and Cynthia Lafferty

This month, Cynthia Lafferty, owner of Doak Creek Native Plant Nursery, emphasizes the importance of native pollinators in our gardens. They need our help. Over the 17 years we have lived in Eugene, I have switched from the big, old and beautiful of plants to the easy-keeping, beneficial native ones. They are still beautiful, but more diverse and can do better in a changing climate. Plus, they attract native pollinators and many bird species.

Creating habitat for pollinators

Greetings, fellow plant lovers. If you are able to visit our mountain meadows, you will see a succession of flowers blooming spring through fall — all abuzz with bumblebees, tiny pollinator bees, butterflies and birds. How can we create this wonderful habitat in our yards? Here are three pointers to help get you started.

1. Plant with 60 percent or more of native plants from our eco-region. While many bumblebees, smaller bees and butterflies will sip nectar on non-native flowers, over 90 percent of our insects rely on native plants for their life cycle. Many butterflies and moths are species-specific and will die without their critical plants.

2. Plant canopy layers in your yard to expand habitat. Taller and shorter trees make up the upper canopy, mid canopies are created by taller shrubs of varying heights and lower canopies are made up of small shrubs, flowers, grasses and ground covers. If you have room, an Oregon white oak supports more than 500 different species of wildlife.

For smaller yards, cascara grows 25 feet tall; its little yellow flowers are a magnet for bees and the dark late-summer berries are relished by 40 different birds. Mid-canopy shrubs of different heights like twinberry, mock Orange and Pacific ninebark offer both flowers for pollinators and berries for birds. Some great low-canopy shrubs include salal and snowberry.

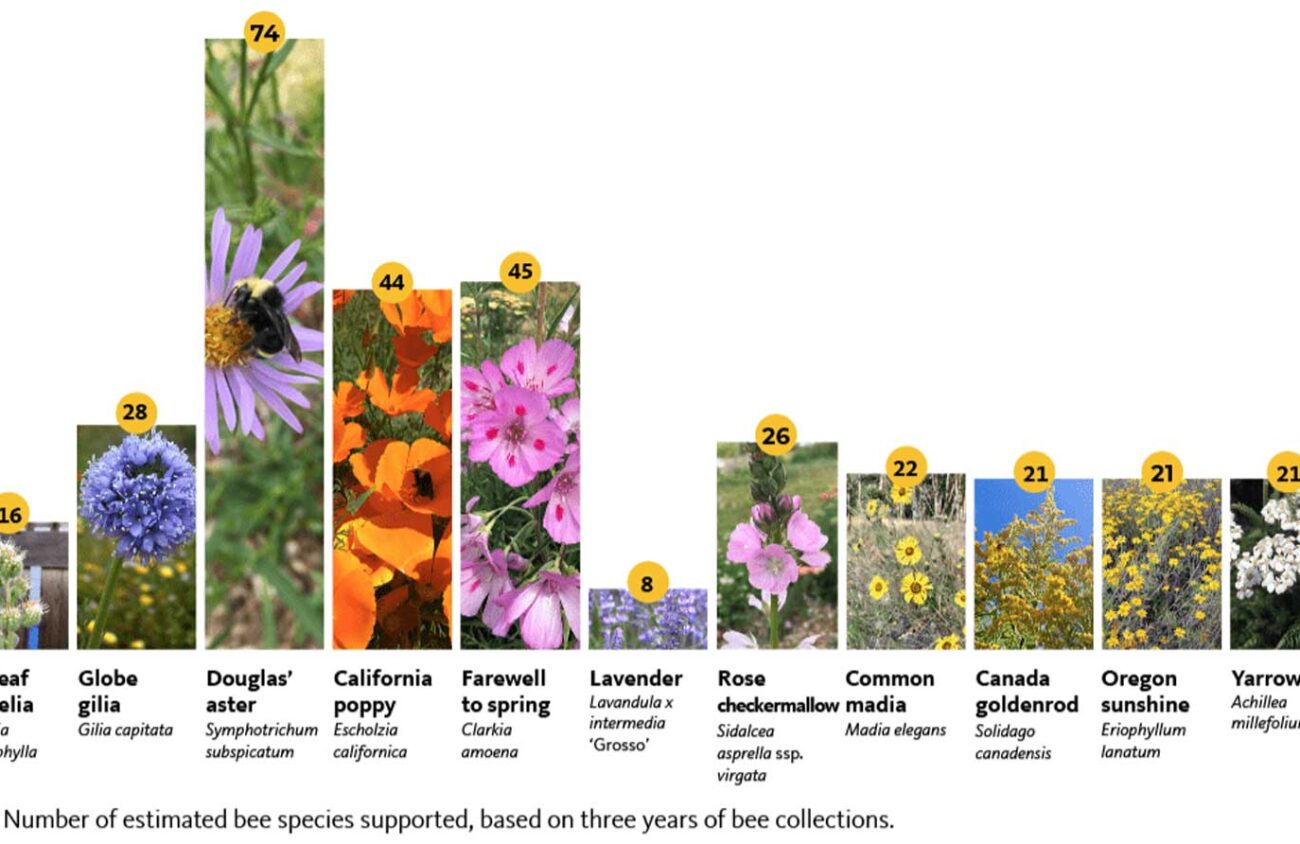

3. Use succession planting so there will be continuous blooms for pollinators. For example, a collection of plants in a sunny garden could include checkermallow, lupine, milkweed, yarrow, goldenrod, fireweed, pearly everlasting and Douglas aster. This group of drought-tolerant plants will ensure constant flowers from spring through fall. For best results, cluster plants in groups of three to five at the back of a flowerbed or below the shrubs in a pollinator hedgerow.

Note: Douglas aster is listed as the highest western Oregon fall pollinator plant by Oregon State University, supporting 74 species of native bees — compared to lavender, which only supports eight species of native bees. For creating habitat for both birds and pollinators in your yard, include the widest possible range of flowers, heights, and types of plants. A great resource is the Habitat Haven Backyard Certification program (LaneAudubon.org/habitat-haven).

“Oregon’s pollinators need our help,” Environment Oregon State Director Celeste Meiffren-Swango said in a recent press release on June’s National Pollinator Week. “But so far, our state leaders haven’t taken much concrete action to build up their habitat or protect them from deadly pesticides.”

She added, “Twelve U.S. states have restricted the sale of bee-killing pesticides called neonicotinoids (neonics). Oregon had a chance to join that group in its 2025 legislative session, but a bill to restrict neonic usage didn’t pass out of committee.”

She goes on: “Inhospitable environments created by human activities, such as the elimination of native flowering plants used for foraging and habitat used for nesting, distinctly threaten pollinator species.”

Concerned? Let your state representative know as they are the ones who can legislate against neonics. Oh, and plant natives when possible.

The Garden Palette is a monthly column coordinated by Kim Kelly. Writers include longtime EW garden columnist Rachel Foster, Master Gardener John Fischer, arborist Alby Thoemsin and Cynthia Lafferty of Doak Creek Native Plant Nursery. Have a gardening question or tip? Email Gardening@EugeneWeekly.com.