For six summers, volunteers of the Whiteaker Block Party have been hard at work adding the Block Party era to the neighborhood’s long and colorful history. The Whit has been home to indigenous people, farmers, families, hippies, anarchists, artists and small business owners — all folks who benefit from creative thinking. This thinking just might be the most continuous generational thread winding through this place that has seen many changes.

And those changes were big, Aidan Holpuch says. Holpuch has been coordinating the Block Party’s Whiteaker History Booth, which since 2008 sets up year after year on the Porch of Distinction at 1032 W. 3rd Ave. “The Whiteaker is the oldest neighborhood in Eugene, so it’s pretty rich with history, and I thought that the block party would be a perfect time to highlight some of that.”

Holpuch and Ken Guzowski of the historic preservation office, which has donated materials to the display, set up a booth with photos from the late 1800s and early 1900s, plus a map and the Whiteaker plan for development. Over the years, Holpuch has added to the display with help from both institutions and other residents.

Before it was the neighborhood Eugeneans recognize today, the Whit was inhabited by the Kalapuya tribe, which lived throughout the Willamette Valley and beyond. The Whiteaker inherits its name from John Whiteaker, Oregon’s first governor, who bought 10 blocks there in 1890. The name stuck after the Whiteaker School was built in 1926.

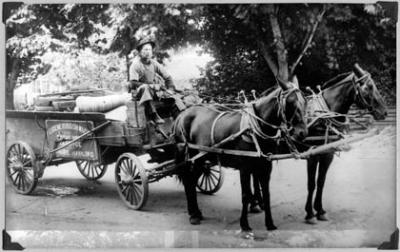

During an early Block Party, Holpuch found a photo of the house she lived in at the time, now transformed into apartments, shortly after it was built in 1912. She learned its original residents were Oren Bray and family. “I also discovered that he was the rubbish collector for the whole neighborhood,” she says. “There’s actually a picture of him with his rubbish cart full and two mules that was taken, I believe, in front of the house.” Being able to find that personal connection to history, Holpuch says, is one of the most exciting things about the booth.

When Eugene started zoning in 1948, the Whiteaker had already transitioned from more agriculturally oriented land to a mix of residential, commercial and industrial uses. It stayed that way, and a lot of creative types have embraced the lower rents and constant bustle. The area has been called Eugene’s “bad neighborhood” to the amusement of people who have experienced larger cities.

In the late ‘90s and early ‘00s, the Whit gained fame for being “a test kitchen for the principles of anarchy,” according to the L.A. Times. Longtime resident Tim Lewis (of If a Tree Falls fame) remembers Icky’s Tea House as emblematic of what the Whiteaker was at that time.

“It was a place that homeless people, poor people, anarchists, a wide variety of types of freaks that existed in that area could go and not spent money,” Lewis says. Lewis recalls Icky’s as an early home for the Cascadia Forest Defenders, Cascadia Alive, Eugene CopWatch and a venue for punk bands. It was also one of the first places in Eugene for free email checking, he says.

That not-little-boxes-made-of-ticky-tacky feel extends to the present; in 2007 Esquire Magazine called this little slice of Eugene “one of the weirdest neighborhoods in America.”

So what sort of unique heyday is the Whit in now?

Lewis says that “to some extent,” the gentrification of the neighborhood feared by residents in the ‘90s and ‘00s has taken hold, and he says the Whit is more small business-oriented than it was in that era. He adds that he likes and goes to some of the new places. While gentrification might have edged in, what has come along with it tends to be non-chain, and locally owned, other than a 7-11 at 5th and Blair.

Holpuch says the booth needs artifacts from the last 30 years to have a consistent timeline, “but in general we would love anything.” Next year, she says, she’s interested in adding people’s stories to the mix. “I don’t know exactly what that would look like and how we would present it, but I’m sure we could get a crew together and brainstorm about what that could be,” Holpuch adds. Those interested in adding to the collection can leave their contact info on a sign-up sheet at this year’s booth.

The Block Party started as a neighborhood cleanup, then grew to have more music and a celebratory atmosphere. Today, the Whiteaker Block Party is still all-free and all-volunteer (even the musicians!), and organizers say they’re always in need of extra volunteers to clean up the next day. Just show up!