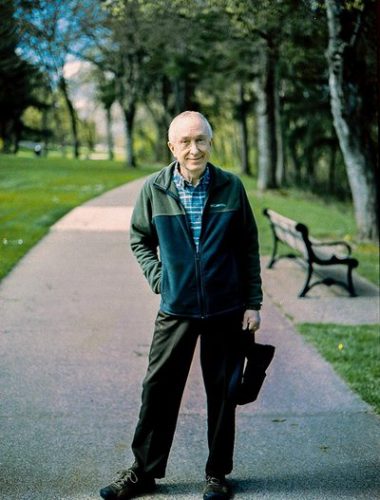

James Earl lives in Eugene and is a professor emeritus of English at UO. Previous essays by him can be found by searching for his name at eugeneweekly.com. Valley River Inn will host an exhibit of 26 of his riverbank photos in its lobby starting April 10.

Walking

I decided to walk to the Oregon Coast from my house downtown, out past Fern Ridge, up to Triangle Lake, down through Deadwood and Mapleton, and out to the beach south of Florence — 72 miles. Walking it would be a definitive act, yes! But this tired old body would have to walk 24 miles a day for three days. My wife, Louise, suggested I might want to get my legs in shape, so I started walking a 5-mile loop on the Riverbank Path. In a few weeks I got my time down from 95 minutes to 70, but then I stopped.

Months later, one day in February, I just got up out of my reading chair, where I more or less live, and went back to the park. This time I took a camera, and instead of trying to walk faster I decided to walk longer. In a few weeks I extended my loop from 5 to 7 miles, then 9, 11, and finally 12 and a half at a leisurely 3 mph; the first time I walked all 12 and a half miles it took 4 hours, 10 minutes. Oddly, I’d never walk it that fast again.

This 12-and-a-half-mile circuit meanders right through the middle of Eugene, from the Knickerbocker Footbridge on the east edge of town, by I-5 and Glenwood, to the Owosso Footbridge in the northwest, by Beltline and Santa Clara. All that way and back again on the other bank, and you never cross a city street. You pass three other footbridges, too — Autzen, DeFazio and Greenway — for a variety of big river vistas. It’s an extraordinary city park, but most Eugeneans take it for granted.

After that first 12-and-a-half-mile walk, I bought some real walking shoes, but they made my feet hurt, so I had to slow down. At 2 mph they were OK, but, I wondered, what’s the point of just dawdling on the bike path? At this speed I’m only an old guy hanging out in the park — and 12 and a half miles would take six and a half hours. The slower I walked, however, the more I saw, and the more pictures I took. At 2 mph the landscape began to brighten and come alive, and about half way around the circuit, suddenly everything but everything became beautiful. Of course: It was spring. I said to myself, out loud, “That’s great! I don’t have to walk to the Coast.”

Parks

That’s my kind of walking — aesthetic, meditative. But Eugeneans want to know, “Why go to the park, when there’s real wilderness nearby?” The answer is, “Because it’s a park.” A city park isn’t wilderness; it’s a big garden. Parks are planned, planted, landscaped, mowed and managed; they have reasons for being, and their own aesthetics. They’re a form of art.

The American city park was invented by Frederick Law Olmsted in the mid-19th century. He adapted it from the English city park, which was modeled on country parks of English lords. When Romantics like Wordsworth started raving about Nature, parks everywhere became less formal, made over as picturesque recreations of a lost pastoral world. Why a pastoral landscape in the middle of a modern city like London or New York? Because in the age of Dickens, cities weren’t beautiful, healthful or relaxing; rather, factories, poverty, crowding, violence, disease, filth and noise were everywhere. City parks were developed to cure the urban fantods. In Olmsted’s America the city park was both democratic and therapeutic:

It is one great purpose of the park to supply to the hundreds of thousands of tired workers, who have no opportunity to spend their summers in the country, a specimen of God’s handiwork that shall be to them, inexpensively, what a month of two in the White Mountains or the Adirondacks is, at great cost, to those in easier circumstances.

It is a scientific fact that the occasional contemplation of natural scenes of an impressive character is favorable to the health and vigor of men. The want of such occasional recreation results in a class of disorders the characteristic quality of which is mental disability, sometimes taking the severe forms of softening of the brain, paralysis, palsy, monomania or insanity, but more frequently of mental and nervous excitability, moroseness, melancholy or irascibility, incapacitating the subject for the proper exercise of the intellectual and moral forces.

So that’s why I go to the park! The Riverbank Park is Eugene’s Central Park, its Romantic, Olmsted-ian park. It’s there to provide relief from the insanity of modern life. Olmsted called the city park a “pleasure ground,” but it’s really a form of therapy.

The River

I want a park where, as Norman Maclean says, “All things merge into one, and a river runs through it.” He learned that fishing, I learned it walking. As I walk, all kinds of things pass by on my one hand: lawns, trees, playgrounds, picnic areas, gardens, grasslands, wetlands, woods — i.e., parkland; but also EWEB, the UO, a railroad, two restaurants, a stretch of highway, a shopping center, housing and a school — disappointing at first, but it’s OK if the pastoral illusion is broken here and there, because on your other hand there’s always the river — and the river never disappoints.

One of the first things a river teaches you is that it’s always there: “Old man river, he must know something but he don’t say nothing, he just keeps rolling along.” But the river does say something. Maclean says, “A river has so many things to say that it is hard to know what it says to each of us.”

And let me add, it may say something different each time you visit. Sometimes it’s the river of time, or history, or life, sometimes it’s Being and Becoming, or the Tao, or the stream of consciousness. It’s one river when you think about it, another when you look at it, another when you take off your shoes and step in it — and there’s no better place than a river to learn that you can’t step in it twice.

The first time I left the bike path to explore the walking trails (and why did that take so long?) I stumbled onto an idyllic spot that only a few people seem to know about, a kind of grotto almost, with overhanging trees and a long flat rock extending out into the river. I walked out on the rock and took in the vistas and the sound of the rapids. The river seemed to say, “What are you waiting for, stupid?” so I took off my shoes and put my feet in. In front of me was an arrangement of large rocks, so beautifully arranged you’d think a Zen garden had been flown in from Japan and reassembled there. I jumped from rock to rock, took a photo, eventually got back on my walk, but could hardly wait to return. The next day I went back, and it was gone. What? I searched up and down the river, checking the photo. I met a guy named Bob who walks his dog there every day. He said, “Did you notice the river rose almost a foot overnight?” We were standing at that very spot. No wonder the river called me stupid.

Russian poet Arseny Tarkovsky writes:

He kicked off his boots and put

his feet into the water, and the water

began talking to him, not knowing

that he didn’t know its language.

Oregon poet William Stafford writes, probably of the Willamette, “What the river says, that is what I say.” My favorite lines about rivers, though, are by T.S. Eliot:

I do not know much about gods; but I think that the river

Is a strong brown god — sullen, untamed and intractable,

Patient to some degree, at first recognized as a frontier;

Useful, untrustworthy, as a conveyer of commerce;

Then only a problem confronting the builder of bridges.

The problem once solved, the brown god is almost forgotten

By the dwellers in cities — ever, however, implacable,

Keeping his seasons and rages, destroyer, reminder

Of what men choose to forget. Unhonoured, unpropitiated

By worshipers of the machine, but waiting, watching and waiting.

His rhythm was present in the nursery bedroom,

In the rank ailanthus of the April dooryard,

In the smell of grapes on the autumn table,

And the evening circle in the winter gaslight.

The river is within us.

Riverbank Park

In my year of walking I learned a lot about the park. It was inaugurated 100 years ago, in July 1914, with music, dancing, swimming and fireworks. Eugene was recovering from typhoid and sorely needed what the new park offered: peaceful, therapeutic trails and vistas on the butte and along the river below. It was an Olmsted-ian “pleasure ground” for hikers, swimmers, campers, bicyclists — but especially in 1914 for walkers like me, who used the park as Olmsted imagined, for “the proper exercise of the intellectual and moral forces.”

Fifty-five years later Valley River Center paved over a big stretch of the north bank; Eugene, shocked, responded with plans to save the rest. The riverbanks had served as landfills, junkyards and garbage dumps for decades. Gradually the city stitched together Skinner Butte, the Rose Garden, the Maury Jacobs and West Bank Parks, Delta Ponds, Alton Baker Park and the Whilamut Natural Area; and now, the Ruth Bascom Riverbank Trail System is finally complete enough to be experienced as one big park, half-recreational, half-natural areas. Last year it was named one of the 10 best city bike trails in America by Bicycling.com, and I vote it a great walking park, too. There are miles of beautiful maintained footpaths unknown to bicyclists.

Still, it’s not really a park, it’s a “system.” Much of it is under city of Eugene Parks and Open Space, but much is under a crazy quilt of other agencies. I hope someday it becomes one big official park. In the meantime, the city’s planning a centenary celebration for this summer.

It’s well worth celebrating. If on a summer day you raft the 6 miles down the Willamette through Eugene, you’d hardly know you’re in the middle of a city of 170,000 people. Once upon a time, not that long ago, the river flowed through cottonwood forests 2 miles wide; today just two thin lines of these our tallest indigenous trees survive along its banks, beautiful and graceful, towering over less majestic oaks and firs, a natural signature for Eugene. In summer they look like a forest; in winter when they’re naked, you see how few remain. I hope they never disappear.

Nature

What else have I learned in my meditative walks along the riverbank? Hard to say because when I walk I try not to think. That’s what meditation is, not thinking. My best hours on the riverbank aren’t spent with words, but looking and listening. One day I was back on that long, flat rock with my feet in the water when my cell phone rang. My daughter, far away, was unhappy; could I help? I told her to go down to the creek and put her feet in the water. She did, and the therapy worked. Her friends declared me a wise dad, but it was only the river speaking.

Wordsworth, who grew up by a river, describes the effect of its voice:

Didst thou beauteous Stream

Make ceaseless music through the night and day,

Which with its steady cadence tempering

Our human waywardness, composed my thoughts

To more than infant softness, giving me,

Among the fretful dwellings of mankind,

A knowledge, a dim earnest of the calm

Which Nature breathes among the fields and groves?

Much of the time words can’t be helped, at least not in my case. Sometimes the river flows with words, composing my thoughts, mostly about Nature and Beauty. On the subject of Nature, my year in the park led me to four conclusions. They’re not new ideas, it’s just that I just finally “got” them.

1. Unlike the human world, Nature has no thoughts, intentions or desires; it just is.

2. By definition, therefore, it’s perfect.

3. We may love Nature, but it doesn’t love us back.

4. The love you feel for it anyway makes it beautiful.

That the world doesn’t love us, but just is, is a hard lesson; but sometimes when you’re happy enough to love it anyway, simply because you’re alive, it seems to light up and becomes beautiful. Do we love it because it’s beautiful, or is it beautiful because we love it? What’s the difference? It’s an illusion that Nature loves us, but feeling that it does has a therapeutic effect, at least on me.

Beauty

There’s a term for the kind of beauty one finds in a park: the picturesque. It was invented in England in the 18th century as a technique for landscape painting but quickly became a theory of landscape design itself. Perhaps it’s superficial, sentimental, aristocratic, but if you take your easel to the park, you’ll probably put it where the picturesque tradition leads you. Same with a camera: You look for a certain kind of light and shadow, contrast, things in groups and alone, mood, texture, a diagonal, a focal point (not too close to the center) — painters and photographers have ideas about “composition,” what makes a picture beautiful. City parks make it easy, because they’re intentionally picturesque.

Landscape professionals think of the picturesque as a middle category between the beautiful and the sublime. A leaf, a flower, a tree can be beautiful but not picturesque; wilderness, mountains and vistas can be sublime — overwhelming — but not in city parks. In our park, vistas from the five bridges do offer hints of the sublime, though, so I look for pictures in all three categories. The pictures now cover a year. The only story in them is the turning of the seasons. That day when my feet hurt, and I slowed down, and fell in love with the park, and everything became beautiful — a mythical moment — I started taking pictures of everything — trees, grasses, rocks, water, birds, graffiti, reflections, shadows. Later, when I came to understand the park better, I learned to see it better. When February came around again, I knew to focus this time on that thin line of naked cottonwoods, bathed in a pastel late-afternoon light. Suddenly they had something to say about age, endurance, dignity.

Well, that’s my therapy. I’m not sure what drove me to it, but I know what I found. The ancients believed that beauty’s the presence of a goddess in something. For me, each photo records a moment when the goddess touched something, and it brightened; which is to say, I fell in love with a little piece of Nature in the park.