When I was a boy, my father, a former music teacher, joked: “There’s nothing worth listening to beyond Bach. Bach wrote it all first.” But I was a child of pop music and, in the words of Morrissey, classical music said “nothing to me about my life.”

My dad’s attitude aggravated me to no end. I wanted to prove the music I loved was worthy and that not everything of value had been written by some dead white guy hundreds of years ago. As I grew older I learned to love Bach, and my father’s words made some sense; while there’s a stunning panoply of music to appreciate in a lifetime — from pop to classical forms — Bach did in many ways lay the groundwork for what we call Western music.

In particular, Bach’s Cello Sonatas, Goldberg Variations and Well-Tempered Clavier are cathedrals of human creative achievement, packing as much emotional punch as the pop songs I continue to love; what Shakespeare is to Western drama, Bach is to Western music.

The return of the world-renowned Oregon Bach Festival got me thinking: In 2014, an age of dub-step, hip hop and EDM, is Bach still relevant? What would the old master think of contemporary pop? I solicited the input of some Eugene-area musicians, scholars and teachers, hoping to finally settle the old score between my dad and me — is there anything worth listening to beyond Bach?

“Bach’s musical innovations prefigure or predict things that later composers and musicians did,” says Loren Kajikawa, assistant professor of ethnomusicology and musicology at the UO. “I don’t believe it is fair to judge more recent music by comparing it to Bach,” Kajikawa continues, explaining you might find a chord progression or melody in a pop song that resembles one of Bach’s compositions, but are these really the most meaningful things we can say about music?

For example, is Bach’s “Air on a G String” really an adequate substitute for Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale?”

“‘Whiter Shade of Pale’ is a powerful song,” Kajikawa asserts, “not just because of the Bach-style chord progression, but also because of the vocal style, which was inspired by African-American soul artists like Ray Charles.”

Milo Fultz, graduate of the UO School of Music and Dance and principal bassist of the Boise Philharmonic, says a lot of the music people are doing now was done at least 50 years ago. “All music is contextual,” Fultz continues. “Maybe you just like the sound of it, maybe it speaks to you on a spiritual level, maybe you can see how the music of our time has evolved from there. There are a lot of angles to choose from that all depend on what you have experienced.”

“Bach’s brilliant approach to counterpoint, for example,” Kajikawa adds, “is not going to help you understand what makes minimalist composer Steve Reich’s music great, nor what makes blues musician Muddy Waters great, nor will it help you understand what makes hip-hop DJ Grandmaster Flash great. To hear all music through Bach (or to expect all music to work like Bach’s music works) is to unnecessarily narrow one’s understanding and appreciation for the beauty and diversity of music making.”

So what would Bach think of the strange and wonderful world of modern music making?

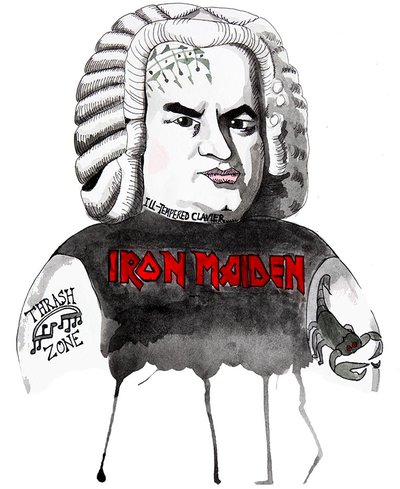

“You might be surprised by one of the places in recent popular music where one can hear echoes of Bach and other baroque composers: heavy metal,” Kajikawa says.

“If Bach looked at contemporary pop music, he would see now what he saw then,” Fultz says, “craftsmen who are hired by rich patrons to make them money. Bach spent most of his time as the composer for a church, who paid him a hefty salary to put out works as fast as possible.” Speculating Bach might take offense that modern music has largely moved away from religious inspiration, Fultz jokes, “but he would also probably be really confused about what a phone was, too. So you have to give him some credit.”