Some 65 dams came down for various reasons in the U.S. in 2012, according to National Geographic, and Oregon rivers are averaging three or four intentional dam breaches a year. But one troublesome dam, Soda Springs, still remains on the North Umpqua River, despite recommendations for its removal by a federal agency, numerous environmental organizations and even a study funded by the project’s owner, PacifiCorp. The story of why this remote dam remains standing is not widely known, and it boils down to corporate profits versus the environment, with bad timing thrown in.

Soda Springs is operated by PacifiCorp on Forest Service land in cooperation with multiple government agencies. It stands in a deep, shaded canyon of columnar basalt cliffs, high in the Cascades 60 miles east of Roseburg, an area made famous by Zane Gray and generations of steelhead fishers. Its gray concave face shows 60 years of stains, cracks and patches, but it’s both old and new. The dam now has a large square hole cut through it at the reservoir waterline and an elaborate 600-foot fish ladder system that is considered a marvel of engineering. The $60 million ladder took four years to design, three years to build and was completed in November 2012. Flood debris last year did major damage to part of the new fish screening system, but some salmon, trout and perhaps lamprey are finding their way up the ladders and pools, rising 60 feet to the reservoir to continue their migration upstream to spawn.

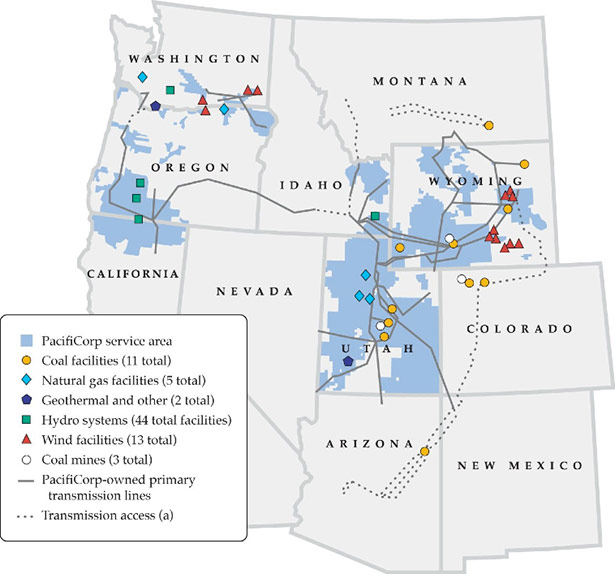

Soda Springs is important because, even though it is small, it is the first obstruction in the North Umpqua Hydroelectric Project, a 194-megawatt system of eight dams, canals, penstocks and generators. Salmon and steelhead run smack into the dam after swimming 160 miles from the ocean. And the dam has a big impact on the 6-plus miles of river above it to Toketee Falls, a natural obstruction as the river flows from its headwaters at Lemolo Lake.

Why it remains standing

The dam was relicensed for 35 years in 2001 under the more environmentally stringent rules of the Electric Consumer Protection Act of 1986 and other legislation.

Relicensing followed a 17-year debate. The dam had been recommended for removal by the U.S. Forest Service, a multi-party “Cooperative Watershed Analysis” (contracted and paid for by PacifiCorp), the North Umpqua Foundation, Umpqua Watersheds, Steamboaters, Umpqua Valley Audubon, Native Fish Society, Trout Unlimited, WaterWatch, Pacific Rivers Council, Oregon Natural Resources Council, Sierra Club, Earthjustice and others. Nobody wanted to keep the highly profitable dam — except PacifiCorp, which was under pressure at the time to turn more profits under the new ownership of Scottish Power. PacifiCorp was supposed to be a highly profitable $10 billion investment in the growing energy field, but “PacifiCorp has been a disappointment to Scottish Power investors,” wrote reporters Heather Simmons and Jad Mouawad in The New York Times in May 2005.

A “settlement committee” involving PacifiCorp, various government agencies and non-governmental groups formed to study options for the dam in the 1990s, but Scottish Power bought PacifiCorp in 1999 and “they refused to go along with dam removal and PacifiCorp walked out of the settlement process,” says Stan Vejtasa of Umpqua Valley Audubon. “PacifiCorp then claimed the hydro plant was only marginally economic (a huge lie!) and they could only afford to spend $25 million on environmental mitigation efforts.” Vejtasa says PacifiCorp wanted to spend that money not on fixing the dam but on projects “that had nothing to do with hydro.”

Vejtasa has expertise in such issues. He’s now retired and volunteering with Audubon, but he worked 12 years as an engineer in the utility industry, evaluating the economics and technologies of power generation, including hydro. He challenged PacifiCorp’s numbers during relicensing. “I showed the project was a real money maker, producing power for less than one-third of the current wholesale price of power,” he says. “I also showed PacifiCorp could afford to spend as much as $200 million on mitigation and the project would still be economic.” He says he also demonstrated that Soda Springs Dam could be removed and the system would “still have significant peaking capacity” for power production by better using Toketee Lake for water storage.

PacifiCorp, he says, did not challenge his analysis, so it then abandoned its economic “propaganda” and turned to science. “Of course, their science said they could merely install fish passage and the aquatic functions of the river would be restored.”

PacifiCorp conceded that the “watershed analysis concluded that the best way to benefit native anadromous fish near the North Umpqua project was to remove Soda Springs Dam,” wrote project manager Monte G. Garrett in a statement published in 2010 on RenewableEnergyWorld.com. “Removing the dam, however, would require PacifiCorp to provide the dam’s re-regulating function in another manner or discontinue the valuable peaking nature of the project.” Peaking refers to the ability to meet high demands for the sale of electricity.

In other words, dam removal didn’t pencil out for the multi-billion dollar corporation. But keeping the dam has turned out to be very expensive, compared to the estimated $5 million to $10 million to remove it. And PacifiCorp had earlier estimated the $60 million fish ladder would only cost about $12 million. Garrett said the company expects to lose about $370 million during the 35 years of this license “due to increased bypass flows, as well as $125 million in capital construction projects.” PacifiCorp has estimated the project will result in a 1 percent rate increase.

Several groups who felt snubbed in the settlement process, including Audubon and Steamboaters, filed a lawsuit to try to stop the relicensing agreement. “The lawsuit was totally not worth it,” Vejtasa says. “Even if we had won, it did not guarantee the removal of the dam. It only required the Forest Service to do their own Environmental Impact Statement of the project. It just gave PacifiCorp two more years to operate the hydro project without any mitigation.”

The relicensing agreement did force PacifiCorp to commit to about $125 million worth of modifications throughout its North Umpqua hydro system over the next decades. The system includes multiple dams and generators and 44 miles of canals and flumes. So far, elaborate screens have been installed to keep small fish from getting sucked into turbines, a huge tailrace barrier was installed at the Slide Creek powerhouse upriver from Soda Springs to keep fish from getting injured in turbine outflows, water flows have been increased at other bypasses, thousands of tons of gravel have been added to enhance spawning beds downstream, logs have been installed across the riverbed to slow gravel erosion, leaky canals have been fixed, some wildlife passages were built over canals and escape steps were built to reduce the number of deer and elk that get trapped and die in the canals each year.

Getting regional attention

The fight over relicensing went mostly unnoticed in media outside of Roseburg, but it did get the attention of environmental groups around the Northwest, and at least one group went looking to twist the arms of people in high places.

“We were involved early in the relicensing but we pulled out when it was clear that dam removal was not an option,” says John Kober, executive director of Pacific Rivers Council (PRC). “We did, in fact, make a last-ditch effort to reach out to Warren Buffett prior to the building of the enormous fish passage facility. We had a connection to a woman who is his bridge-playing partner, but alas he was not receptive to our overtures.” (Buffett bought controlling interest in PacifiCorp from Scottish Power in 2005 for $5.1 billion.)

Kober says PRC is “highly skeptical of the bypass and still believes the Soda Springs Dam should have been removed. Nonetheless, our focus will be to track the performance of the bypass, and we will insist that they fulfill their obligations under their new license.”

PacifiCorp has shown some cooperation, says Kober. “I have high regard for their fish biologist, Rich Grost, who serves with me on the board of directors of the North Umpqua Foundation. I believe he is doing everything he can to make sure they are doing what they promised.”

Penny Lind, executive director of Umpqua Watersheds, wrote an op-ed in the Roseburg News-Review during the relicensing process, saying, “It will be in the many details that we determine how ‘innovative, historic, balanced and victorious’ this agreement is. The claim that balance has been struck with this agreement appears to be displayed through dollars for access and continued use.”

Lind continues, “Scottish Power/PacifiCorp retains their generating capabilities, exports the energy to the highest bidder, not local residents, and the profits go to a multinational corporation. What a deal!”

|

| Left: The fish ladder at Soda Springs Dam has 59 steps and pools. Right: The tailrace barrier at Slide Creek keeps fish away from turbulent water discharging into the river from the turbine. Note the canal above the river that carries water into the large pipe that feeds the generator. Photos by Ted Taylor |

The trouble with dams

Dams can provide flood control, hydro power, irrigation and recreation, but dams get old, are expensive to repair under new rules and are under increased scrutiny as biologists, engineers and other experts refine their understanding of what happens when the natural flow of water is impeded:

• Dams can fail with age, earthquakes or sabotage — with potentially catastrophic results downstream.

• Migrating fish passage is reduced or eliminated, affecting the entire ecosystem and its nutrient cycle. Insects, birds and mammals are also affected.

• Dams can also affect Native American sacred sites and traditional fishing practices.

• Miles of natural gravel spawning beds are no longer accessible above the dams, and spawning beds below the dams suffer from lack of fresh gravel, woody debris and nutrients. Diminished spawning beds can hurt commercial and recreational fishing, both in rivers and in the ocean.

• Dams can conflict with newer state and federal mandates regarding native fish restoration. Trapping and trucking salmon around dams on their up-river journeys is difficult and expensive, and dams can interfere with smolts trying to swim downstream to the ocean. Remediation projects, such as elaborate floating fish traps above dams, can cost millions to design, build and maintain.

• Some smaller dams can accommodate fish ladders, but many large concrete and rockfill dams that provide irrigation, such as Hills Creek and Cougar, cannot due to fluctuating reservoir levels of up to 100 feet. Fall Creek Dam is unique in that the reservoir can be drained entirely through a gated spillway when smolts are ready to go downstream to the ocean. But returning salmon need to be trapped and hauled around the dam by truck.

• Water flows and temperatures are altered, with impacts on sensitive species. Towers in reservoirs can be used to control water temperature outflows, but are expensive.

• Massive sediments build up behind dams and eventually reduce their holding capacity. When dams are breached, the rapid erosion of reservoir sediments can be very destructive downstream. National Geographic has a video of the 100-year-old Condit Dam being breached at wkly.ws/1og.