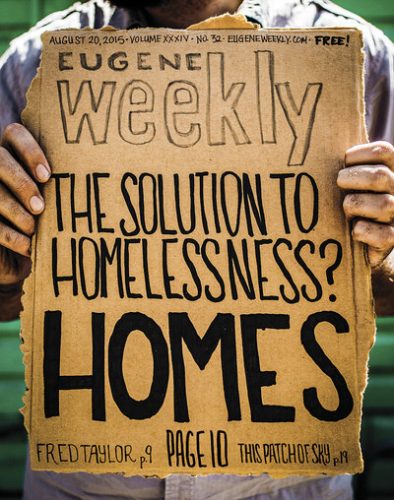

Walk through downtown Eugene and you’ll see shops, restaurants, bars, kids on bikes, artists, business people, random pedestrians … and part of this quirky city scene is an assortment of panhandlers, travelers and unhoused residents not unlike those seen in downtowns across America.

Walk though downtown Salt Lake City and it feels a bit like Disneyland. Weirdly clean, it too has bars, restaurants and shops. The downtown mall, City Creek Center, has a manufactured creek running charmingly through its tidy, paved center.

And while it has its share of Mormons on mission (more accurately, members of the Church of Latter Day Saints) in the requisite white shirts and dark ties, it also has a typical scene of shoppers and strollers as well as people sleeping on benches and sitting on planters.

It’s not just SLC’s cleaner-than-clean downtown façade that made Utah’s unhoused stand out to me. I was surprised because Salt Lake City, as I read in several articles before traveling there in July, has figured out the solution to homelessness.

But as I wandered from my hotel in search of coffee (which, like alcohol, is easily purchased in SLC despite rumors that the church forbids it) there were indeed homeless people, panhandling, riding mass transit and generally doing what the unhoused do in every city — surviving.

I met up with a local alternative news weekly reporter who quirked an eyebrow at me when I told him I had come to see Salt Lake City’s solution to homelessness.

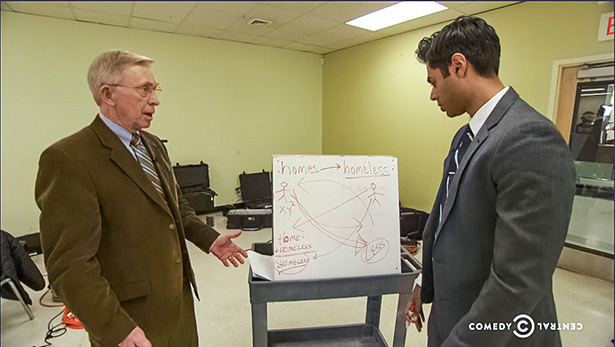

It didn’t seem that odd a request. I’d read the story in Mother Jones and The New Yorker, seen the piece on NationSwell. The Daily Show even did a segment in January with correspondent Hasan Minhaj sitting down with Lloyd Pendleton, who had been the director of the Utah Homeless Task Force, to discuss (tongue in cheek on Minaj’s part) how SLC had reduced its chronically homeless population by 72 percent.

We hopped on the TRAX, Salt Lake’s light rail, which is free downtown and popular with the housed and unhoused alike in the area. We hopped off not far from downtown, near a sparsely populated mall. A short walk later, we were heading down the street toward The Road Home’s Salt Lake Community Shelter and a cluster of other homeless services.

We walked through the throng of people waiting on the sidewalk for the day shelter to open. Not far from where drug dealers were blatantly peddling their wares stood families with small children in strollers, hoping for aid.

A young woman sitting on the sidewalk, looking exhausted, maybe a little spaced out, told us she comes to the shelter for food, a shower and a place to rest. A police officer going through the belongings of someone whose car was parked on the street was largely ignored by the rest of the 50 or so people scattered around the homeless services.

Given the scene outside, I wasn’t too surprised when, arriving at the front desk and asking the receptionist if I could talk to someone about how Salt Lake City had solved the “homeless problem,” she said: “How we did what?”

Her tone of shock and skeptical glare spoke volumes.

Yet, to a certain extent, Salt Lake City has solved a significant portion of the homeless issue in a way that other cities haven’t. The solution is simple and relatively inexpensive: Housing First. Giving the homeless a place to live; not temporary shelters, giving them homes.

But as the staff of The Road Home, a shelter with around 800 beds, will tell you, SLC has not eradicated homelessness. Utah serves as both a model and a reminder for Eugene. The city has made a huge step in the right direction, and it’s one that Lane County can emulate — if this area, like Salt Lake, can collaborate on large-scale solutions and, just as importantly, keep moving forward.

|

| The Daily Show’s Hasan Minhaj Questions how giving houses to ‘Moochers’ solves homelessness |

The Salt Lake Solution

In that way the internet has of exaggerating things or getting details just wrong enough to make them better or worse than they really are, the news that began to float around social media last fall and into the winter was that Utah, the red state that has gifted the world with Mitt Romney and execution by firing squad, had somehow solved homelessness.

The Daily Show jumped on that news, as it does any news that sounds a bit odd or over the top, like two-headed fish or the BP oil spill. Hasan Minhaj interviewed Lloyd Pendleton, who has since retired from the state of Utah but still speaks and consults on homeless issues.

After pointing out the ridiculous things cities have done to discourage the unsheltered from being visible — from fining them for sleeping outdoors to arresting them for sitting down — the satirical segment says: “Salt Lake City has taken the next step, by removing homeless people from the streets altogether,” then shows Minhaj fruitlessly and ironically hunting for people who might be living in cardboard boxes.

“Did you hide them underground?” he asks Pendleton. “Did you convert them from Mormon to gay?”

No. Nor from gay to Mormon either, Pendleton deadpans.

So how did they do it?

“We gave homes to the homeless. Yes, it’s simple. You give them housing, and it ends homelessness,” Pendleton says.

His response on The Daily Show is deadpan, but he’s not at all kidding. Since 2005, Utah has reduced the numbers of the chronically homeless by 72 percent, according to the state’s 2014 Comprehensive Report on Homelessness, and not gone broke doing it, by providing housing.

Providing housing to the homeless actually means cities spend less money.

Utah has a 10-year plan to end chronic and veteran homelessness by the end of 2015, and it’s doing this by using a “Housing First” model. Housing First is, quite simply, the effort to focus on quickly providing permanent housing, not temporary shelter, to those experiencing homelessness, and then providing the needed services. It’s the opposite of the typical model, which demands people who might be mentally ill or addicted first go through recovery, get dry or get treatment before “earning” shelter.

Eugene really doesn’t have true Housing First, but we could, and many homeless advocates want it. In some ways, the temporary camps such as Whoville, which have been shuffled around the city, as well as the less temporary Opportunity Village Eugene (OVE), are a step in that direction. But while those solutions, as well as shelters such as the Eugene Mission, provide temporary or even longer-term shelter, they are not Housing First. Places such as OVE and Emerald Village Eugene (SquareOne Villages) require that residents not use alcohol or illegal drugs.

|

| Pastor Dan Bryant |

The federal government defines as chronically homeless any unaccompanied person who has been unhoused for 12 months or for four times in the previous three years and has some other existing condition such as mental illness or drug addiction, according to Dan Bryant. Bryant is pastor at Eugene’s First Christian Church and is executive director of SquareOne Villages. Then there are the situationally homeless, Bryant says, individuals or a family that might be homeless for six months or nine months.

It’s the situationally homeless that have been the focus of Bryant’s work. “Frankly, I’m focused on the other end, higher functioning, not frequent flyers,” he says. “Folks who just need a little bit of help.”

Transitional housing programs such as SquareOne Villages’ tiny houses are innovative, effective and have gotten their share of national attention, too. ShelterCare’s The Inside Program has provided Housing First-type transitional homes and case management for the mentally ill since 2006. But as anyone who lives in Eugene knows, particularly those who live under bridges or in camps alongside rivers, the innovations have not “solved” homelessness.

Meanwhile in Utah, Pendleton is enthusiastic at the steps the large-scale implementation of the Housing First model has made to solve the problem — veteran homelessness is basically at a functional zero, he says. According to Pendleton, the key to the solution is collaboration as well as buy-in from groups and politicians. He says SLC was part of a 2003 federal plan to end chronic homelessness involving a pilot project in 11 cities. The Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness was a $35-million program for housing and support services that combined Housing and Urban Development funds with other resources.

Utah learned about the Housing First program in New York City, but Pendleton says what works in NYC doesn’t necessarily fly in Utah, so a pilot Housing First program was established in Salt Lake. He says the project, Sunrise Metro, took on 17 challenging chronically homeless people, and SLC learned “if we can house them, we can house anybody.” He says that nationwide, Housing First projects show 85 percent of people are still housed after 12 months.

“We became believers,” Pendleton says. It was a “huge paradigm shift, and we did it with our own people.” Housing First soon had buy-in at all levels and across political lines in Utah, and that, Pendleton says, made it possible.

Why Housing First?

But what good does it do to put homeless people in homes if they still have the problems that led to them being unhoused in the first place? Financially it makes sense, Pendleton says. He estimates it costs $10,000 to $12,000 to house a chronically homeless person, but it costs the government $20,000 to deal with them on the street and up to $40,000 in other cities.

Transitional shelters, in the long run, are not cost effective if the homeless spend the whole time there, Pendleton says. If one chronically homeless person gets a bed, then 11 other situationally homeless people can use that bed the chronic person has been taking up. According to the state of Utah’s statistics, 3.9 percent of Utah’s homeless are considered chronically homeless or experience homelessness for long periods of time, but the chronically homeless take up a disproportionately large share of shelter beds and services.

Bryant says that much higher on-the-street cost has to do with the many contacts the unhoused have with public health and police — trips to the emergency room and to jail. But, he cautions, Housing First programs still need to be supplemented with services, and funding is always an issue.

Utah repurposed existing funding when it got under way with Housing First. Pendleton says, “I was not willing to go say, ‘Give me $10 million to implement this new idea.’” But once the program showed success, it got champions at high levels and even outside donors, in addition to pulling from federal, state and local funding.

Back at The Road Home, the nonprofit’s executive director Matt Minkevitch says while housing the chronically homeless has made a difference, the work is not done. “Candidly, I got concerned when I started sensing members of our coalition doing a victory dance,” he says.

“We’ve made some measurable progress,” Minkevitch tells EW. “Collaborations have been good. We had a collective focus,” with groups from government officials to housing authorities “agreeing that we really wanted to make a significant impact on those who were living in the shelter as opposed to brief episodes of homelessness.”

But, he says, there is still much to learn, and homeless advocates are only scratching the surface. While tremendous progress has been made, he says the 800-bed Road Home shelter “is putting out mats tonight” for people to sleep on. Right now, the homeless issue in SLC is stalled, Minkevitch says.

“The part that makes it all the more energizing, frustrating and encouraging is we’ve done this,” he says. “The most challenging people I’ve known for two decades, they are in housing, they heal, they do better. Do they go 12-step and become completely sober?” he asks. “No, but there’s a moderation in behavior.”

Housing First is “incredibly encouraging, but we haven’t scaled it up, and we need to step it up. Urban America needs to do this,” Minkevitch says.

He’s looking at homeless families and at an economic situation and a housing situation that is leaving too many people on the edge. Minkevitch says that just down the street from the shelter, public funding is going to put in a high-end project that will have apartments for rent at $1,000 per month, the kind of places people at The Road Home might aspire to, but right now, or maybe forever, are out of their reach.

“We are creating the kind of environment where someone living in poverty is in constant peril of homelessness,” he says. For people at or below the federal poverty line for whom just getting their hours cut at work could mean losing their homes: “If they are not making $15 an hour, they can’t afford an apartment in Salt Lake City. Am I not describing a lot of cities across America?”

Our tax credits are not going to create housing for those people on the edge, Minkevitch says.

Where to go from here

Looking at Eugene, the city’s Multi-Unit Property Tax Exemption has given 10-year tax breaks to higher-end apartments and student housing. But a recent Eugene City Council decision means that developers are now required to give 10 percent of the MUPTE exemption to a city fund dedicated for affordable housing, or developers can designate a third of the units in the development at affordable rents.

But even with innovative projects such as SquareOne Villages and various Eugene Safe Spot rest stops, Eugene could be doing more, both for the chronically homeless as well as for the situationally homeless and those on the edge. Salt Lake is getting better, Minkevitch says, but also needs to do more. He tells me since I was there only last month a new police officer in the area has cracked down on the drug dealing outside the shelter.

Jacob Fox of the Housing and Community Services Agency of Lane County (HACSA) says the agency provides Section 8 (housing vouchers) and public housing for 5,000 households in Lane County. A significant number of those people are coming out of homelessness or transitional housing. Residents can use alcohol, but not illegal drugs, he says.

Fox is on Lane County’s Poverty and Homelessness Board that he says is “currently conducting due diligence to see if Housing First makes sense for our community.” He says the board is a committed group of individuals who are thinking out of the box, and that the group will know by the first quarter of 2016 if it will attempt to develop or aquire a 50-unit building that would serve the chronically homeless. Meetings of the board are open to the public.

On the state level, Bryant says that there was a Housing First bill in the Oregon Legislature this past session, House Bill 3420. The bill didn’t make it out of committee, but it would have established Housing First pilot programs in Eugene and Albany. Rep. Val Hoyle (D-West Eugene and Junction City) was one of the sponsors, and Bryant says the goal is to “restart and reshape and get something ready for short session in 2016.”

According to Pendleton, it’s that sort of thinking and collaboration, as well as buy-in from officials and funders at all levels, that makes Housing First work. Housing First needs a “champion,” he says. “The mayor or a county commissioner needs to say, ‘This is a priority, and I’m making this a commitment.’”

He adds: “It can be done. We know the solution; it’s housing. You just need to make the commitment.”

A recent filing by the federal Department of Justice in a Boise, Idaho case may also give hope to the impetus to provide homes for the unsheltered not criminalize those who live on the streets. The filing says:

“ … when adequate shelter space does not exist, there is no meaningful distinction between the status of being homeless and the conduct of sleeping in public. Sleeping is a life-sustaining activity — i.e., it must occur at some time in some place. If a person literally has nowhere else to go, then enforcement of the anti-camping ordinance against that person criminalizes her for being homeless.”

And if Housing First works in Lane County, and we put forth a big, collaborative effort to free up shelter space and keep families at the edge of poverty out of homelessness while supporting those who are situationally homeless as well as those on the fringes through innovative programs, then, finally, we might be closer to “solving the homeless problem.”