In the United States we are taught at a young age to desire impractical shiny things under the premise that more luxury equals a life lived successfully.

But if our desire for an upper-class aesthetic is a social construct, what part of the goods we consume is real?

Artist Anya Kivarkis ponders this question of the space between consumption and reality by recreating jewelry as sculpture. Since completing her M.F.A. in 2004 at the State University of New York (SUNY), Kivarkis — who is head of the University of Oregon’s jewelry and metalsmithing program in the School of Architecture and Allied Arts — has been cranking out more elaborate pieces in ever larger shows.

She says a slim number of museums in Oregon are interested in showing contemporary crafts, which means that most of her work is shown further afield.

In June, Kivarkis was one of five Oregon artists to win the 2016 Hallie Ford Fellows in Visual Arts for her outstanding work — that’s a $25,000 unrestricted award presented by the Ford Family Foundation.

With the fellowship, Kivarkis says she plans to prepare works for her next solo exhibit (a ’40s-era, French-inspired collection) in October 2017 at the Sienna Patti Gallery in Lenox, Massachusetts. Equipment and manual labor for her work are pricey, Kivarkis says, so a large portion of the award will go toward alleviating that expense.

Kivarkis will also hire alumni and students from the metalsmithing program as studio assistants. Jewelry making is a commitment that takes time, money and all hands on deck.

|

| ‘Carey Mulligan, red carpet 2010’ |

But she doesn’t make jewelry with the intent to sell it as a luxury item. Rather, she wants to provoke questions about jewelry’s purpose by altering its material, surface and context.

Kivarkis’ parents are immigrants — her father is from Syria and her mother from Lebanon — and, as a youngster, she watched them aspire towards a Victorian aesthetic they couldn’t afford.

“I would always deeply reject those things or even ideas of femininity,” she says. “I was always asked to perform some sort of way of assimilating and I think I always wanted to reject those ideas.”

Her complicated relationship with luxury helps her to detach from the American Dream of bettering oneself through material consumption, and yet she also obsessively immerses herself in it.

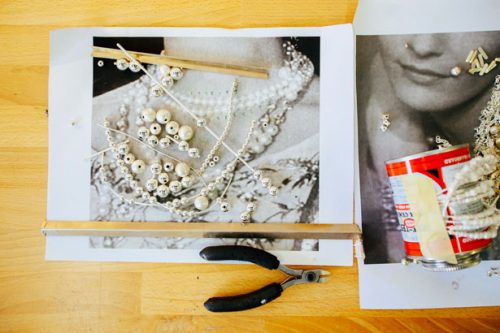

The walls of Kivarkis’s studio are lined with repetitive photos of a necklace dripping diamonds, and her desk is cluttered with piles of reference images — mostly jewelry shots from paparazzi, old films and red-carpet events. Currently she is working on a French-themed bracelet: It has faux jewels, painted white with a chalky finish, that stand in a curved line atop a blunt silver, spine-like wire.

Even for an inanimate object, it looks pretty dead.

Most of Kivarkis’ work looks hyper-realistic as opposed to being an exact replica. She solders, cuts and highlights a particular piece based on where its reference image exhibits a blur or glare, or is cropped by a photo boundary or body part. Sterling silver is her metal of choice, and due to its lustrous nature, she usually sandblasts the material until its surface has lost its luster.

Her work is extremely meticulous. Kivarkis laughs while she explains that some of her pieces take years to complete.

|

| Anya Kivarkis in her UO studio. Photos: Trask Bedortha. |

She is driven by her curiosity of the consumption trends of jewelry dating to the Baroque period. During times of economic fallout, she explains, our desire for luxury goods rises.

Vogue magazine’s 2007 “September Issue” — its largest issue of the year, a style bible of sorts — is a perfect example of this trend. In the moments leading up to the global financial crisis, Kivarkis explains, Vogue released the issue, which oozed glamour, leisure and wealth. In 2014, she devoted an entire series of her work (aptly titled September Issue) to “Je t’aime, Paris,” a spread from the now infamous issue with a Roaring ’20s theme — fitting, since that flapper era sat on the brink of the Great Depression.

“That’s an interesting question of aspiring to live in a different reality than you’re occupying,” Kivarkis says.

Oh, and if you’re dying to know: Yes, nearly every piece Kivarkis makes is wearable. But after you see her work, you may find yourself second-guessing what’s real and what’s an illusion, and what you really want.

To follow Kivarkis’ work, visit her page at anyakivarkis.com.