Shirley Temple once paid a visit and may have rested her blonde ringlets on soft Hotel Benton pillows.

Symmetrically doomed presidential candidates John F. and Bobby Kennedy each stopped in, as did history’s great scurrying mole rat, Richard Nixon.

Built to capitalize on tourist traffic after the highway now known as Route 34 came through the middle of town about 100 years ago, connecting hayseed Corvallis to what’s now Interstate 5, the Hotel Benton was like a rural pageant queen — more stunning for the low brutish frontier edifices skirting her hem.

“It is difficult to measure the impact the Hotel Benton has had on social, commercial, political and cultural structure in Corvallis,” reads the building’s nomination form for the National Registry for Historical Places. “Being located within one block of the Southern Pacific Railroad station, ten blocks from the university and in the heart of the commercial core of Corvallis, the building served as host to nearly every conceivable event or convention for over 30 years.”

Today, not so much.

Business eventually slumped, as did the “quality of clientele” and the hotel’s reputation.

A classy ground floor lobby that once bounced with dancing flappers gave way over time to repetitive office park detailing. Behind the mezzanine bannister now roosts a drab handful of lifeless business offices.

Somewhere in the ’80s, construction crews converted guest bedrooms into 55 single-occupant apartments, for rent exclusively to low-income seniors and people with disabilities. The giant rooftop Hotel Benton sign came down and its name became Benton Plaza.

And that’s that. An all too familiar tale: a proud boom-time relic, another cultural landmark denuded and repurposed.

End of story.

Or is that just the beginning?

Corvallis’ fringe artist champion Bruce Burris says the building once known as the Hotel Benton is keeping secrets, and those secrets have been staring him square in the face for years.

Burris races around his cluttered office like an over-caffeinated bumblebee, juggling dozens of colorful paintings, illustrations, photographs, carvings and sculptures by artists involved in an exhibition titled “We Live Here.”

On display in an office foyer on Benton Plaza’s ground floor, the show collects works of curious vision and astounding talent, made by a small number of self-taught artists and craftspeople who live in the building’s inexpensive upstairs units.

Shortly after moving to Corvallis a few years ago, Burris set up an art program out of the Collaborative Employment Innovation offices in Benton Plaza. CEI is a human services organization that helps people with disabilities find jobs and then assists them in meeting workplace challenges.

Burris’ ArtWorks program does roughly the same thing, but with the purpose of helping clients find opportunities to engage with the art world. “I don’t really like to work, so why would I want to put anyone else in that situation?” Burris asks.

The idea for “We Live Here” began percolating in Burris’ mind after an auspicious conversation months ago at CEI headquarters with artist and writer Patrick Collier.

As Burris and Collier chewed the fat in CEI’s reception area, a series of familiar faces strolled by, one after another, artists each, Benton Plaza denizens all.

That’s so-and-so, Burris said to Collier, he’s a talented photographer who lives in the apartments upstairs. And there’s such-and-such, he’s an incredible writer also living upstairs.

As the list grew, Collier finally interrupted to ask just how many Benton Plaza artists there are.

Burris consulted with on-site social worker Mary VanderLinden, who has worked with the supporting living program at Benton Plaza for almost four years. She estimated there to be as many as 20 resident artists — more than 30 percent of the building.

“We’re so lucky! That’s the kick: Like, if this is what we can see,” Burris says, gesturing to a painting on one of his office’s art-cluttered tables that depicts a cosmos of blinking stars and swirling nebulae over a sea of blue-black infinity by Benton Plaza resident Victor Nyland, “then what the hell are we missing?”

Out of nowhere one day, Nyland picked up a paintbrush and began the first of what would be a series of four vibrant, hectic outer space vistas. His knack for mechanically precise detail work and replicating meticulous patterns is emphasized by a palate that clashes so intensely in some corners that it creates a woozy 3-D effect under CEI’s fluorescent light.

Nyland, though, doesn’t see what the fuss is all about. The spirit moved him to paint, and then it left.

If he never paints again? “I don’t care one way or another,” he says, politely.

Whether he ever picks up another paintbrush “depends,” he says, shrugging his shoulders.

Nyland is so matter-of-factly self-effacing that the guy almost doesn’t even exist: “Says in The Bible: ‘Pride goeth before the fall.’ I don’t want to fall, so I try to stay low.”

It’s too much; Burris can’t get over it. “He did what he needed to do, and he’s off to the next thing. I admire that. I sure get a kick out of a soul who knows himself that well,” Burris chirps. What excites Burris is thinking we’re looking at the tip of the iceberg.

Intentional retirement communities for aging artists are popping up here and there around the country, Burris says. Last year a reporter from the Village Voice explored a building full of aging stage talent in Englewood, New Jersey.

What’s going on here is totally different, Burris adds: Completely by accident and seemingly out of nothing grew an artist colony in Benton Plaza that’s creating works of singular vision and extraordinary ability.

by Trask Bedortha

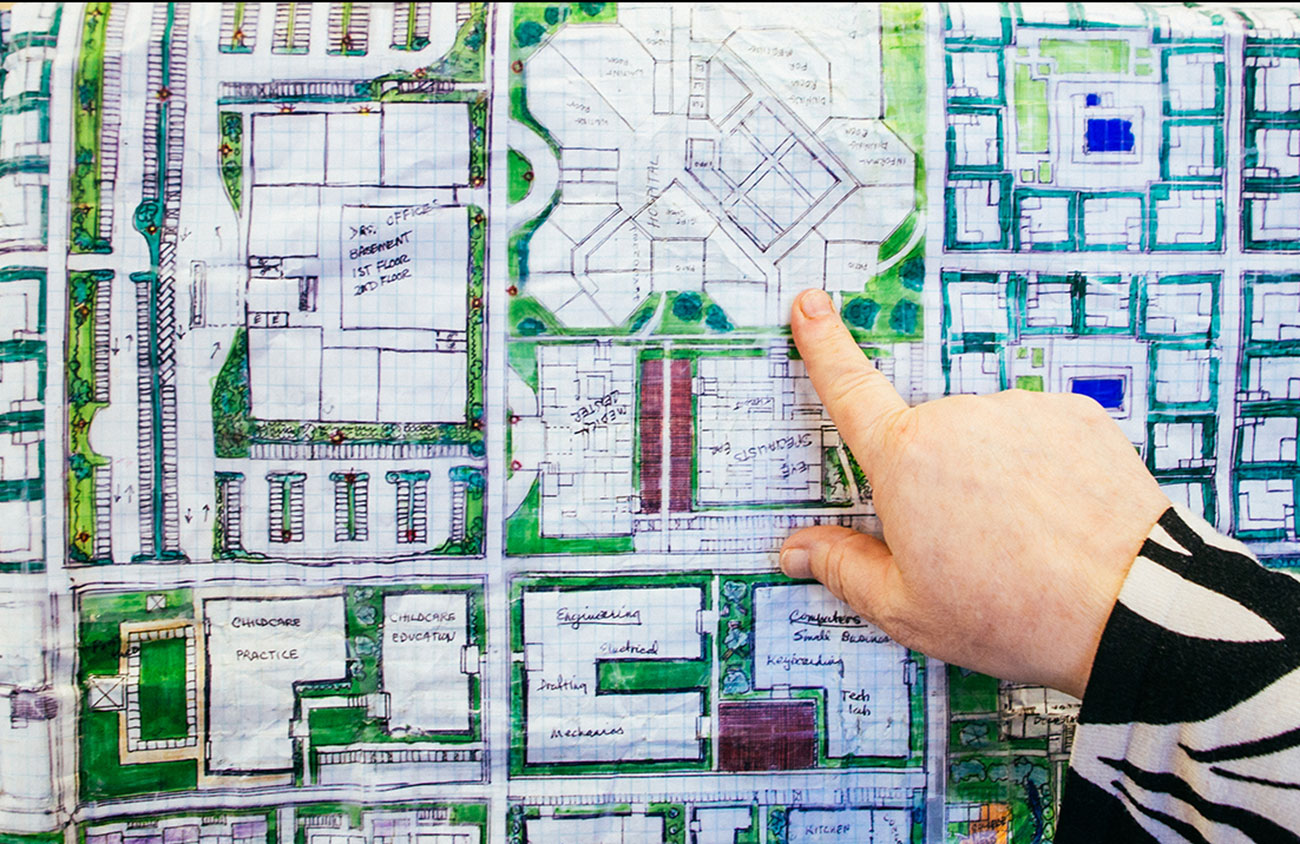

Ruth Van Order’s friends always know where to find her; whatever time it is, the retired nurse and mother of four is likely hunched low over an expanding sea of graph paper and scotch tape in Benton Plaza’s dank community room.

Squinting through thick lenses, Van Order fills in the narrowest detail on an evolving map that is part quilt, part science fiction utopia blueprint, part how-to guide, part autobiography.

Words can’t do it justice.

Nevertheless, one longs to see the real world conform to her painstaking cartography. Van Order plots an alternative reality wherein children get to go to good schools, medicine is free to those in need, energy clean and food forever plentiful.

“And there’d be no money,” Van Order insists.

The layout for the medical center in Van Order’s vision borrows from hospitals where she worked as caregiver for 35 years.

Her varicolored paper world has grown so vast over the years that it takes more than one person to safely unfurl it.

“It’ll be done when I die,” she says, as though there’s nothing at all unusual about her total devotion to a patchwork dream map.

Van Order’s diligence runs counter to Nyland’s easy indifference. The contrast between them suggests “We Live Here” is as much about the unrestrained act of creating as it is about shedding light on Benton Plaza’s secluded art world.

Photographer Rick Kleinowski snaps portraits of Corvallis’ homeless, some of whom Kleinowski knew over the five years he spent sleeping on the streets. One of the images he mounted for the show depicts a clear-eyed “roughrider” who’s currently doing time in Coffee Creek Correctional Facility for “one of her rampages,” he says.

“I used to drink a beer for hours at a time on a bench by the river,” Kleinowski says. “The homeless become part of the background, but they’re real people.”

He’s also into wildlife photography.

Writer Andy Fisher cranks out page after page covered in thick blocks of black typescript that couch an ever-expanding, evermore precise hermeneutic philosophy laid forth in a tangle of winding science jargon. What deep semiotic wells must Fisher tap when he sits down everyday to write?

To many, Amy Turner, who died more than a year ago, was merely the instantly recognizable Corvallis eccentric who smoked cigarettes downtown and wore the most bodacious bouffant wig. What practically no one knew was that Turner drew countless glowing scribbles that blend together hundreds and hundreds of cheerful, laughing faces.

The only commonality among Benton Plaza artists is their inveterate diffidence.

“There’s a lot of pain in this building,” William Steinle says.

Sitar notes weave through the air as trails of incense loop through a clear stream of evening sunlight in Steinle’s modest one-bedroom. The friendly, snowy-bearded music man fires up a few of the humming synthesizers he’s collected over the years.

Steinle gigs here and there under the stage name “ReedyMon” and lives on the fifth floor.

His place is tidy but for a mad-science laboratory of knotted cables that connect Moog synths and midi keyboards to a towering stack of mysterious sound equipment that flanks an enormous terrarium housing Steinle’s bearded dragon.

The old man tweaks a few knobs and presses the keys necessary to create a pulsating Martian soundscape.

“I couldn’t tell you an A from a C,” he chuckles.

His sweet dog Kellygirl dozes off near the motionless wheels of Steinle’s motorized chair. Except for Steinle’s fingers making fine adjustments to a panel of switches and dials, everything is completely still. The music completely takes over and erases any sense of time. He suddenly drops the volume and begins reciting poetry that balances Bhagavad Gita with “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida.”

Hints of grief in Steinle’s poem call back to dark periods in his life, ones he otherwise prefers to gloss over in vague terms. He’s made some bad decisions. Steinle admits to having lived hard and gotten too involved with drugs.

In ’81 he crashed his Harley on a stretch of Arizona highway and lost his left leg.

Steinle knows he’s free to wait out the clock, letting the bottomless font of TV entertainment suck out his mind and soul, but he’d rather use what he’s got left to share far-out music, paintings, poetry or whatever else with the people he loves.

On social worker VanderLinden’s desk in Benton Plaza’s shadowy basement, there rests a small songbird carved from wood. It’s perched on a stump and appears to be about to attack a McDonald’s French fry that’s glued in place.

“One day I told [Steinle] I was ‘happier than a bird with a French fry,’” VanderLinden says, picking up and admiring the beautiful little thing. “I guess that just tickled him.”

“We Live Here” is open weekdays from 9 am to 5 pm until Wednesday, Feb. 15, at the Collaborative Employment Innovations Gallery, 408 SW. Monroe Ave., suite 110, Corvallis.