The life of photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis might serve as a cautionary tale.

After teaching himself the basics of the photography trade, Curtis spent years building up a studio business in Seattle. But just when it was beginning to pay off with successful commissions and recognition, his attention was diverted.

A job in 1895 shooting Princess Angeline — Chief Seattle’s daughter — led to a budding interest in Native American culture. Over the next few decades, his fascination would bloom into a life-consuming obsession.

By the time Curtis died in 1952, he was divorced, destitute and unknown. He destroyed most of his 40,000 negatives in a fit of spite. If he left any lasting legacy, it was more as ethnographer than photographer.

Photographers take heed.

But that’s getting ahead of the story. In 1906, Curtis imagined a 20-volume series documenting “The North American Indian” — his title — in words and photos. With funding from financier J. Pierpont Morgan Sr., he planned to finish within five years.

The travails that followed have been well documented, notably in Timothy Egan’s 2012 book Short Nights Of The Shadow Catcher. No need to recount them here fully. Suffice to say the next 25 years became a never-ending cycle of road trips, photography and fundraising.

Curtis finished in 1930. He’d spent $30 million, in today’s dollars; he was 62, and tired.

In the end, 222 sets of the 20-volume edition were produced. Most have been lost to history or cut up and sold off as individual prints. About 20 complete sets are known to exist.

One is held in the University of Oregon Libraries and Archives. Once owned by Curtis himself, it was acquired in the 1970s, courtesy of a Curtis relative living then in Grants Pass.

Roughly four times per year, the Oregon set is shown to the public, or at least as much of it as will fit atop a few conference tables. On a recent visit, six out of the 20 volumes were on display in the special collections room.

Curator Danielle Mericle and library assistant Jan Smith, a member of the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma, took turns discussing the background and history of the photographs. Then they each chose a stack and leafed slowly through prints.

Oregon’s set is one of the few printed on handmade India proof paper. The photogravures are relatively large, around 18 by 22 inches, and printing them was a labor-intensive process. Also known as Japanese “Tissue,” India proof paper was extremely thin and fragile-looking.

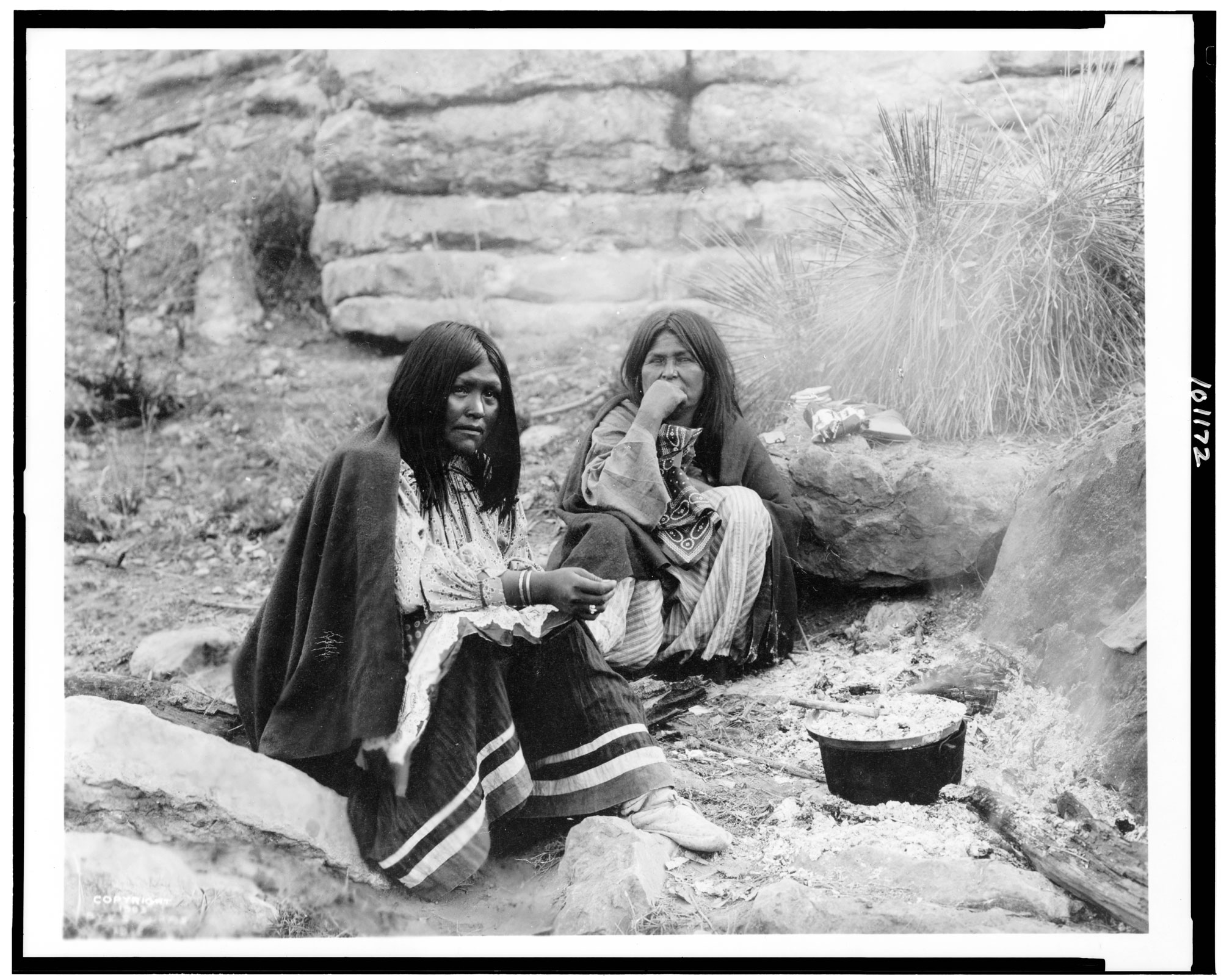

Despite appearances, they were made to last and to stand up to gentle handling. The sepia tones have a rich, subtle scale quite out of step with current photo fashion, which tends more to high contrast and over-saturation.

Looking at these photogravures from a century ago is like stepping into a time machine.

Curtis felt the rush of time too. He was desperate to document Native Americans of the West in their “pure” state, before they’d been sullied and destroyed by European culture. What he did not fully realize is that he was far too late. By the 1900s, the genocide was well underway, and the search for unadulterated tribes was futile.

Nevertheless, Curtis persisted. He probed deep into the frontier in search of the authentic, or at least his interpretation of it. When what he found did not match his ideals of romantic primitivism, he would stage his subjects to fit them, sometimes removing signs of modernity or adding Native artifacts as he saw fit.

From a contemporary perspective, it’s easy to see the flaws in his outlook. The noble savage is a white man’s myth. It did not exist then or now. But Curtis was caught up in the prejudiced filters of the time and his photos reflect that, for better or for worse.

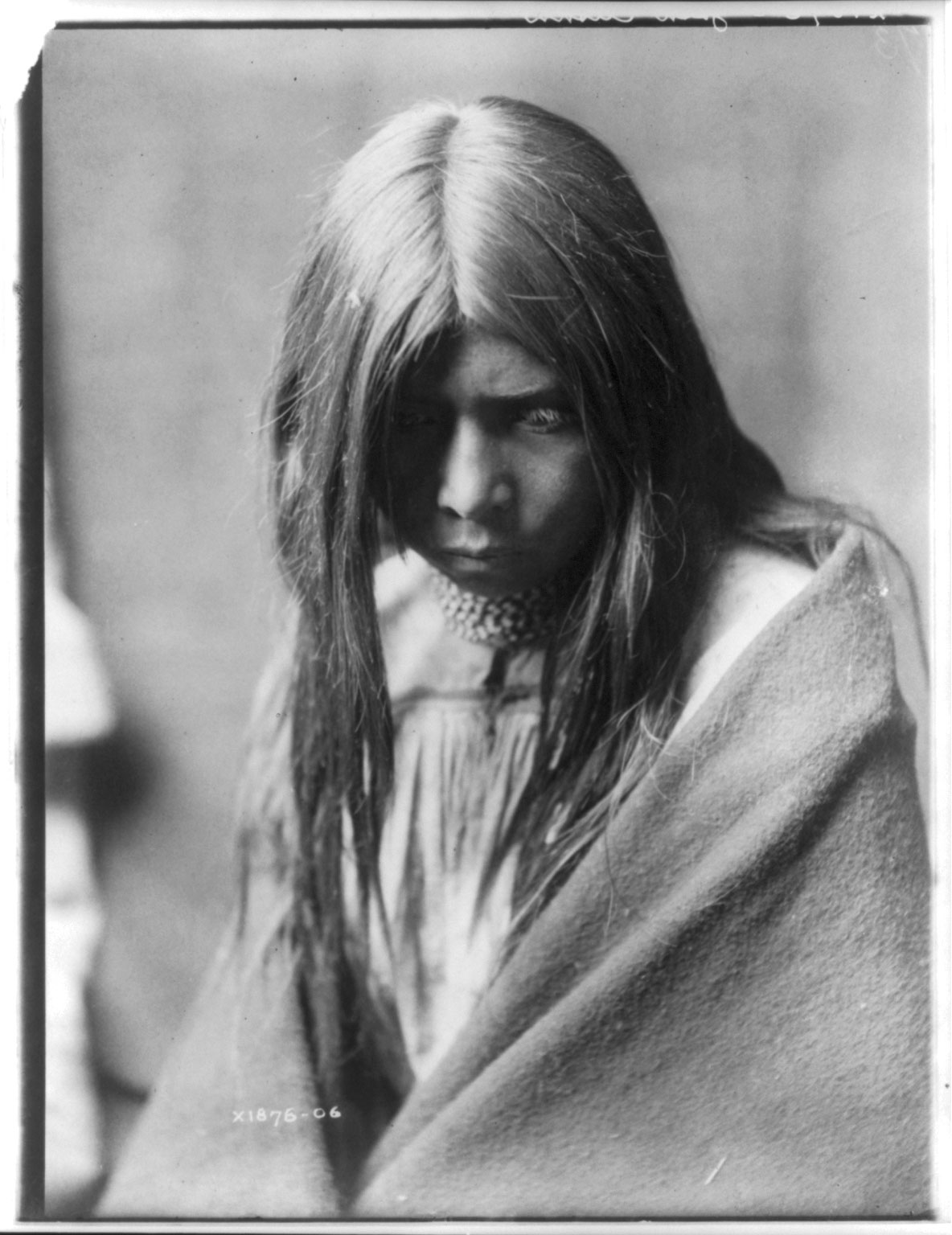

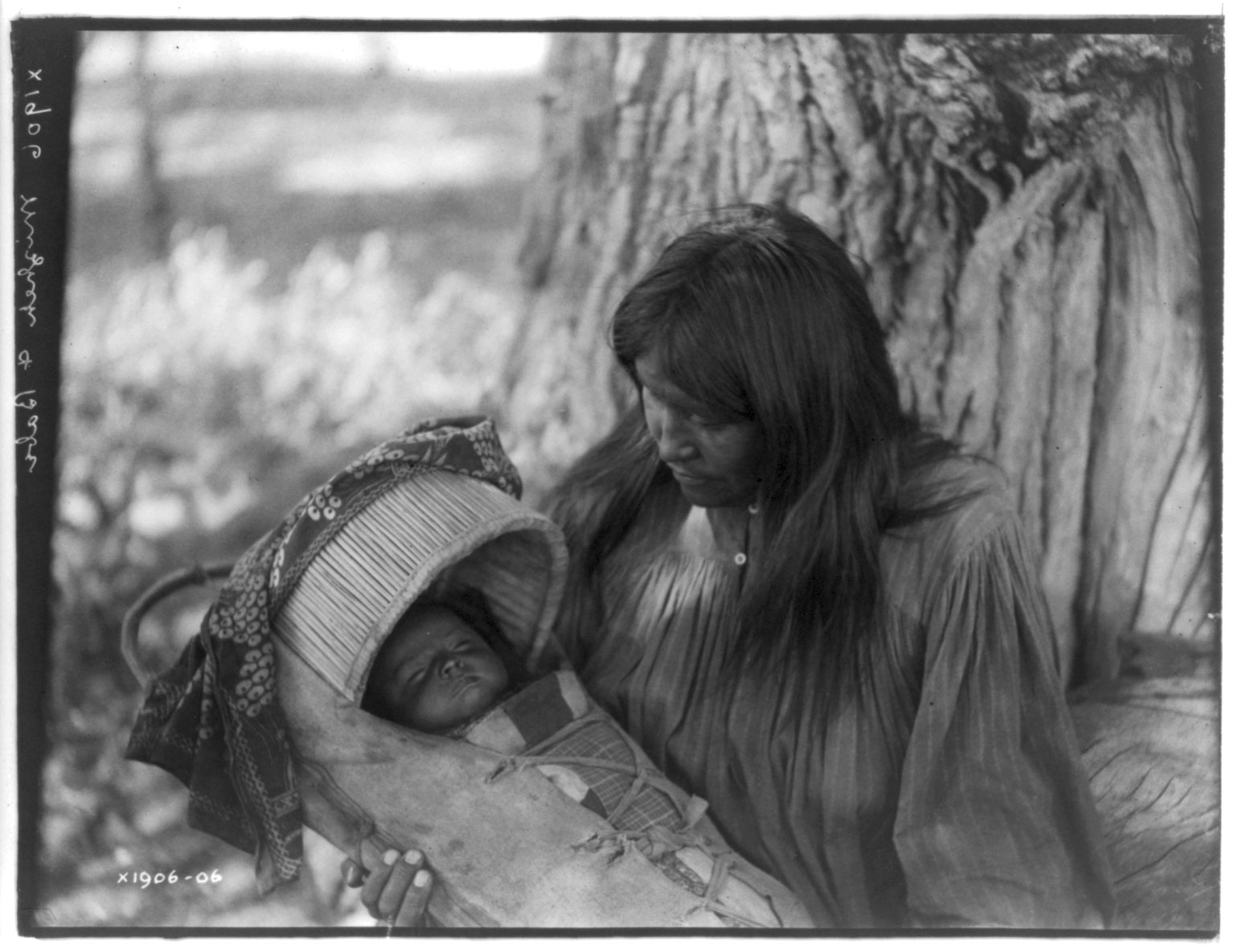

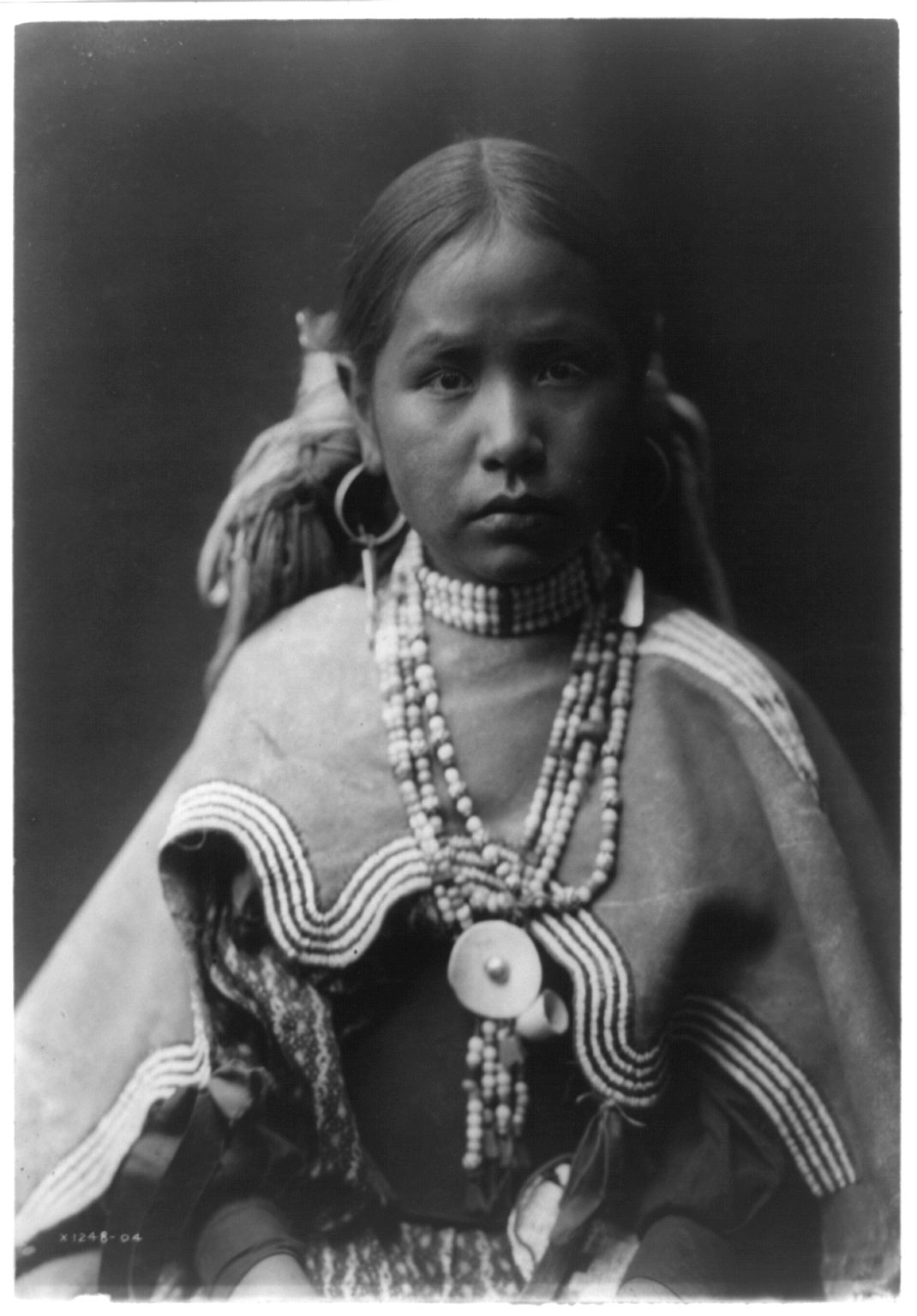

Let’s talk about the better for a moment. As a photographer, and especially as a portraitist, Curtis had few peers. His ability to read a face, to time its expression and frame its essence was exceptional. He used shallow depth of field to great effect, and he had an innate feeling for negative space.

The irony is that portraiture wasn’t necessarily his project goal. Instead he saw himself as an ethnographer, documenting a culture for posterity. To Curtis, the success of any individual portrait was merely a means to an end. Nevertheless, he was damned good.

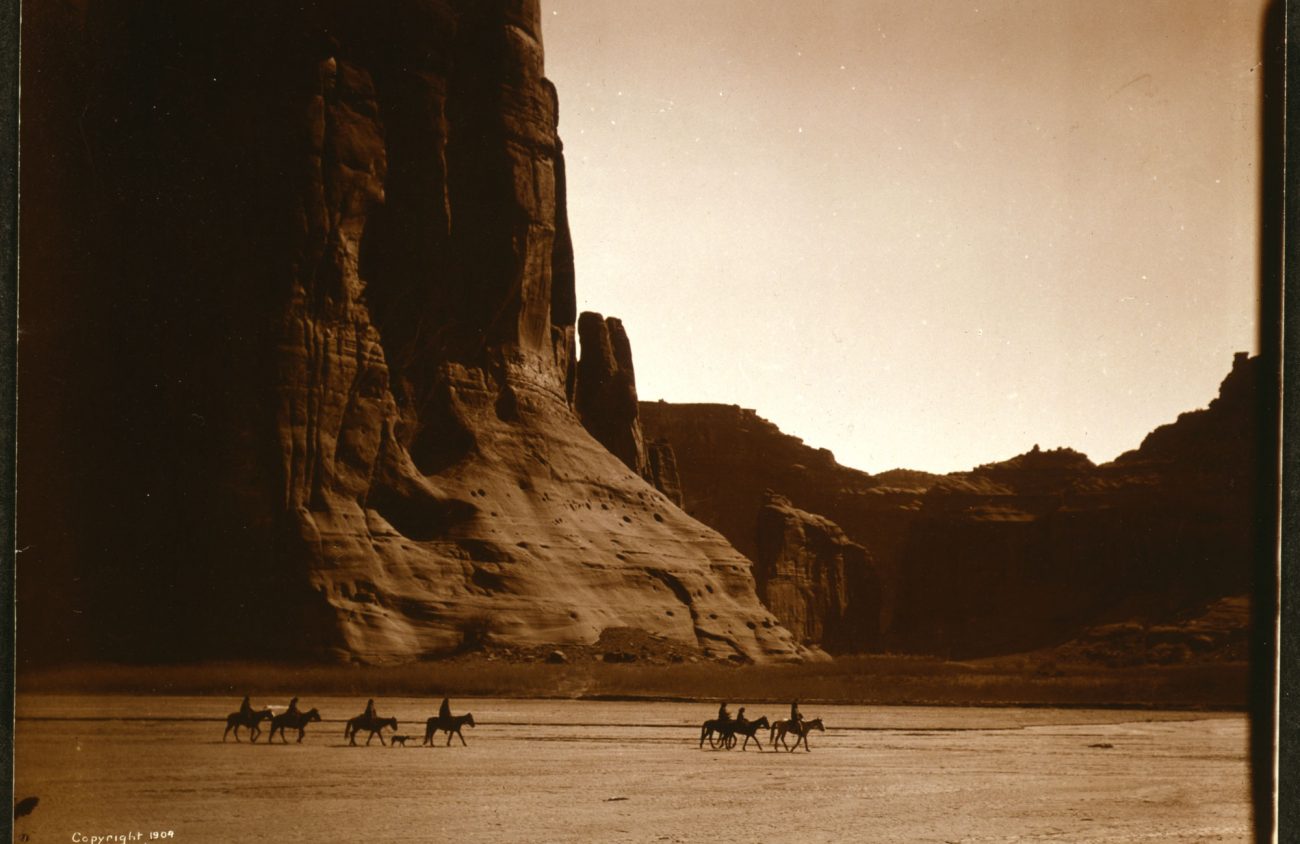

His scenic photographs are also excellent, exemplifying a Renaissance-inspired knack for available light, composition, figure placement and that ineffable je ne sais quoi that makes certain photos art.

Even as he followed the shifting fashions of the time, from the soft, moody pictorialism that dominates the early volumes to the clean modernism manifested in the later ones, his photographic talent never wavered throughout the 25-year project.

Because of their value — the Oregon Curtis volumes have an estimated worth of $1 million to $2 million — they are generally kept behind closed doors. The exception comes a handful of times annually, when they are shared with the public.

The next viewing is scheduled for January 2020. Contact UO Special Collections (library.uoregon.edu/special-collections) for details.