Joanne Gross is a stay-at-home mom with two sons. She and her husband, Scott, bought a house in west Eugene where Scott can bike to work, and she can grow food in her garden. Standing in front of her house on a hot summer evening, while her sons, Ian and Connor, play with their friends on the quiet street, Joanne points to the food she grows in her front yard. What look like decorative shrubs are sweet potatoes, artichokes and herbs. Hops wend their way up the chimney — Scott is a home brewer — and kiwis, figs and grapes adorn the yard. Joanne says it’s the garden that lets them afford to have her stay home, and Scott’s bike commute to the mill keeps him in shape and keeps them a one-car family.

Joanne Gross just wishes she knew a little more about what pollutants are in the soil. If the soil is contaminated, what about the food she feeds her kids?

Turn 180 degrees away from Joanne’s front yard and look across Roosevelt Boulevard and you see a steady plume arising from the nearby Flakeboard America plant. According to its most recent report filed with the Lane Regional Air Protection Agency (LRAPA), the flakeboard plant has the potential to emit 17.7 tons a year of formaldehyde, 107 tons of methanol and 2.17 tons of phenol into the airshed. The nearest home is 500 feet from the plant. Methanol depresses the nervous system and can cause blindness or death. Formaldehyde is considered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to be a probable human carcinogen.

The flakeboard plant “has done a lot to improve their facility,” Joanne Gross says. And indeed its LRAPA operating report shows it has reduced its hazardous air pollutants by 63.9 tons a year. Kelly Shotbolt, president and CEO of Flakeboard, says, “We still use formaldehyde as an adhesive for most of our products, but we use less today than before” due to the proprietary technology that was installed a few years ago.

|

| Joanne Gross. Photo by Todd Cooper. |

|

| Alison Guzman. Photo by Todd Cooper. |

But Gross still wonders what might be in a garden that sits so close to this and other industries with a history of emitting chemicals like creosote, formaldehyde, lead, dioxin and other toxics.

And as she looks at her garden she says, “If the air quality is bad with all the factories, then it stands to reason that the soil might be affected.” But when Gross checked into it, she found out it would cost $70 for one soil sample to be tested for only one chemical, so testing for multiple chemicals in multiple samples is prohibitively expensive.

Joanne Gross is not the only resident of Eugene’s industrial corridor with concerns. West Eugene residents at a community forum in 2010 asked if something was “horribly wrong” because they were experiencing pollution “viscerally,” and they told stories of smokestacks that “stink” and “rain on you.” They told of people with respiratory problems and a lack of access to health care. Some of the Latino residents in the community had concerns that went unheard because they lacked the language and access to voice them.

Beyond Toxics joined forces with Centro LatinoAmericano to look into the health effects of industrial pollutants on west Eugene communities and the people and children who live there. According to their research, a school child in west Eugene breathes in approximately 72 pounds of air toxics a year. The 97402 zip code that makes up west Eugene is home to 99 percent of Eugene’s air toxics, and the area has a higher percentage of minority residents. Centro and Beyond Toxics’ research shows that the west Eugene area is 13 percent Latino, much higher than Eugene’s average population of 7.8 percent Latino. The west Eugene industrial corridor also has about 26 to 28 percent of residents below poverty level. These are the factors, Lisa Arkin of Beyond Toxics says, that make west Eugene an environmental justice community.

Alison Guzman was hired by Beyond Toxics and Centro LatinoAmericano to do outreach among Latino and low-income populations in west Eugene. One resident, who preferred to be referred to by her first name, Josefina, told Guzman that she had lived near the J.H. Baxter plant for five years and often noticed odors that give her headaches. Her children have congestion and have developed respiratory allergies, Josefina said. She told Guzman, “Please help us because honestly this worries me very much, for the health of my children and the health of the adults as well. Sometimes I don’t even want to go out on walks, or I don’t even know if I should go out or not because the odor is terrible.”

When an industry emits air pollution, the question is not whether it can pollute, but how much it can pollute under its permits. The data that Beyond Toxics pulled together comes from the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory (TRI), LRAPA and the Eugene Toxics Right-to-Know database. Arkin says the approach was innovative in that it took into account not just national, but local sources including the air permits from LRAPA.

Lane County’s air issues aren’t only in west Eugene. Merlyn Hough of LRAPA says though he’s unsure of the minority population, he would call Oakridge an environmental justice community because of its low-income residents and poor air quality. LRAPA has worked to change the air quality there through a grant that allows residents to replace older wood-burning stoves with cleaner-burning ones that release less particulate matter and through curtailing wood burning on bad air days.

Hough says LRAPA deals with air quality through industry permitting and implementing air toxics regulation on various industry sources, air monitoring and through working to control “regional risk drivers”: benzene from gas, diesel particulates and PAHs — polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. PAHs are linked to cancer and liver damage among other health issues. Hough says PAHs are largely caused by wood burning stoves.

Arkin points out that on bad air days in the winter, when inversions trap air in the valley, residents are told not to burn their wood stoves, which are sometimes their only sources of heat, but toxic-emitting factories, such as the Seneca Sustainable Energy wood-burning plant, can continue to burn and emit particulate matter. Hough says the EPA has never allowed “intermittent control” and that standards have to be met all the time. Those standards have tightened over the years. Hough says where in the past an industry might have controlled 50 percent of its emissions, now it might control 90 percent.

Guzman says, “Because businesses have the same rights as humans, they should be as accountable as individuals. When LRAPA when gives a warning that we can’t burn, the company should also have to stop burning.”

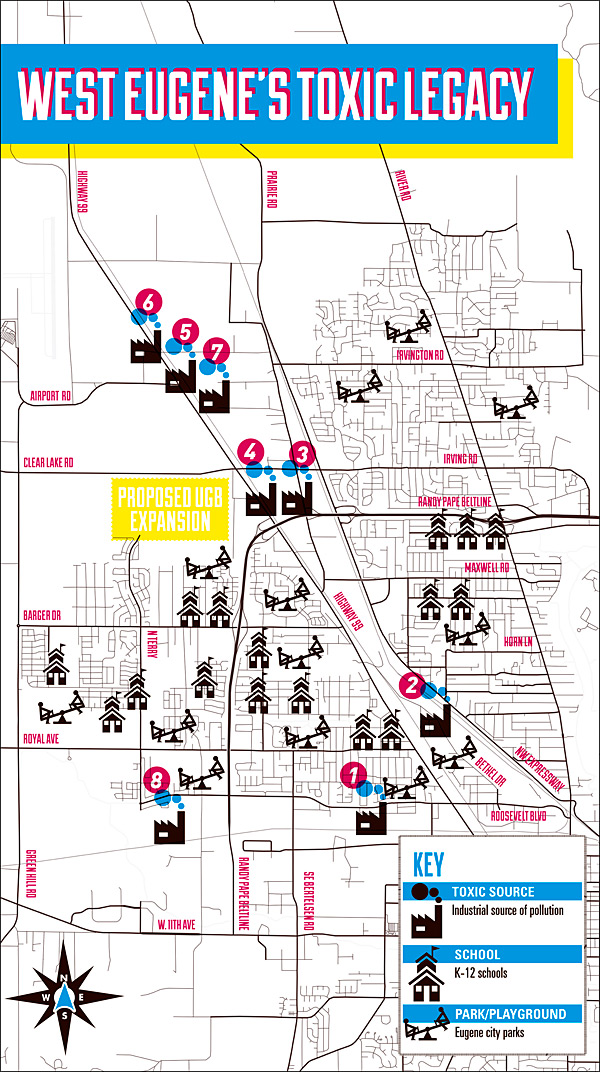

She points out that in west Eugene, “industries are literally neighbors to kids with asthma” and the area has families that are “low income, vulnerable, not as likely to have health insurance.” Mapping done by Beyond Toxics shows schools, parks and homes that are less than a mile from the smokestacks that are puffing chemicals into Eugene’s air. Fairfield Elementary is .6 miles away from the J.H. Baxter plant and the nearest home is 100 feet. The J.H. Baxter plant released 36,000 pounds of “fugitive ammonia” and 943 pounds of creosote in 2010, according to the TRI.

Arkin says Beyond Toxics has gotten phone calls from Bethel teachers and parents who say the bad air on some days has led to kids feeling like they could not breathe during recess time. The goal, Arkin says, in the environmental justice mapping is not to pick on Bethel schools, but rather that schools “should be equally healthy and we don’t think they are.”

Bethel schools superintendent Colt Gill says, “It’s important to me that our kids come to school healthy and ready to learn. We recently celebrated the first anniversary of our Bethel Health Clinic, we are very excited about it, because it really serves students well and addresses some of our health goals.” He says looking at mapping of schools and industries that was done by USA Today,“The Bethel area is not a stand-out, at least not locally. Our district covers 31.7 square miles with a small portion of it near some industry, and I don’t really know how unique that is in Eugene, Springfield or most communities.”

Hough says a problem with the USA Todaymapping — which shows several Lane County schools ranked as having bad air quality — is that it relies only on the Toxic Release Inventory which compiles industry sources of pollution, and ignored benzene, particulate matters and PAHs.

Guzman says that in areas like west Eugene, residents can feel disempowered. They get told if they don’t like the air quality they can move somewhere else, but most can’t afford to. And many residents see the industries such as wood products plants as part of their culture. It’s where they or their neighbors work.

That’s where environmental justice comes in, Guzman says, and grassroots organizations like Beyond Toxics that put pressure on industries and elected officials to regulate them.

Joanne Gross says, “If you don’t live in Bethel, you don’t come here for anything,” and so most Eugeneans don’t see the industries and the neighborhoods near them. But, as she watches her sons run over to the neighbor’s yard to look for kittens, she says, “It’s a wonderful neighborhood where kids can play in the street and with a lot of young families and a lot of young kids.” Down the street, the smokestacks quietly puff into the sky over Eugene.

Environmental Justice

Bring up the environment in Eugene, and most people’s eyes turn outwards. We look at the forests, rivers and public lands around the city, but not at our city itself or the people that breathe its air. Lane Regional Air Protection Agency (LRAPA) permits often refer to the effects that industrial emissions could have on the “class 1 airshed.” But that airshed designation isn’t about Eugene; it refers to national parks that are greater than 6,000 acres and national wilderness areas greater than 5,000 acres, such as the Diamond Peak Wilderness here in Lane County, according to the Clean Air Act. Visibility contributes to the aesthetic nature of the area.

Environmental justice hasn’t gotten much play in Eugene until now. The EPA defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies.”

Beyond Toxics and Centro LatinoAmericano launched the West Eugene Industrial Corridor Environmental Health Project in 2010 with grants from the EPA after west Eugene residents began to express concerns about the new Seneca biomass plant adding to the air issues in their neighborhood. Centro and Beyond Toxics found that the affected neighborhoods have higher percentages of minority, elderly, disabled and poverty-level residents and that the families are disproportionately affected by higher concentrations of industrial air pollutants from surrounding industrial sources. They found that there are 50 air and toxic release sites and two Superfund sites listed within the 9-square-mile area of west Eugene.

One of the areas proposed in Envision Eugene’s urban growth boundary (UGB) expansion lies in the west Eugene industrial corridor. Envision Eugene maps show single-family homes, parks and schools proposed south of Clear Lake Road, just off Highway 99. The maps also show proposed industrial expansion north of Clear Lake Road. Mapping by Beyond Toxics illustrates that the proposed expansion area would be close to existing industries, as well as the newer proposed ones. Concerns voiced by Beyond Toxics about the low-level, chronic and synergistic exposures to toxics families in the new homes would face have led the city to focus more on proposing homes in the LCC basin. — Camilla Mortensen

1. J.H. BAXTER

(Wood treatment and chemical manufacturing plant)

85 N. Baxter Road

Nearby: 7,000 residents live within 1 mile of the plant and it’s 100 feet from the nearest home. Fairfield Elementary is .6 miles away.

Emissions: EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) shows 36,000 pounds of “fugitive ammonia” and 943 pounds of creosote released in 2010. Eugene’s Toxics Right-to-Know database lists only 8 pounds of air toxics, but according to Beyond Toxics, Baxter says it is exempt from reporting its release of creosote compounds to the Right-to-Know database. J.H. Baxter is a Superfund site, has a history of groundwater contamination off-site and was fined $6,000 in 2011 for violating its air permit.

Effects: Ammonia can cause extreme fatigue and respiratory problems. Creosote (made of chemicals such as napththalene) is a probable carcinogen and can cause neurological effects and anemia. Baxter also lists pentachlororophenol on the TRI database. Penta is also a carcinogen and can cause miscarriages and neurological effects.

2. TRAINSONG/UNION PACIFIC RAILYARD

1035 Bethel Drive

Nearby: The nearest homes are a few yards away.

Emissions: The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality says of the railyard “oil and groundwater contamination on the railyard consists mainly of petroleum hydrocarbons, industrial solvents and metals. Outside the railyard, low levels of solvents are found in groundwater underlying portions of the adjacent Trainsong and River Road neighborhoods.” The DEQ says the well water in the area is safe for “outdoor use.” DEQ warns “Solvent vapors from contaminated groundwater can make their way up and into buildings.” Union Pacific has been doing conducted groundwater cleanup since 2005, and the DEQ says “currently vapor intrusion in the Trainsong neighborhood is not a threat.”

Effects: Beyond Toxics says diesel particulates from the train locomotives can cause cancer, heart disease, asthma and pneumonia and warns the pesticides regularly sprayed along the tracks are a public health hazard.

3. MURPHY PLYWOOD

2350 Prairie Road

Nearby: West Eugene neighborhoods

Emissions: Murphy Plywood emits 14,000 pounds of methanol a year, an estimated 29 tons of fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) and 34 tons of PM 10. It emits 74,000 tons of greenhouse gases a year, according to the data collected by Beyond Toxics. The TRI database shows Murphy Plywood emits ammonia and formaldehyde as well.

Effects: Methanol can cause severe body pain, loss of vision and sleep disorders. Formaldehyde is a carcinogen, allergen and asthma trigger. Ammonia can cause extreme fatigue and respiratory problems. Fine particulates can penetrate deeply into the lungs. Short term PM 2.5 can cause coughing and irritation, long-term it’s linked to lung cancer and heart disease.

4. GEORGIA-PACIFIC CHEMICAL

(Koch Industries)

2665 Highway 99 N.

Nearby: Golden Gardens Park, neighborhoods.

Emissions: Under its Lane Regional Air Protection Agency (LRAPA) permit, Georgia-Pacific emits 36,000 pounds of air toxics.

Effects: Beyond Toxics says the top three chemicals are epichlorohydrin, a carcinogen that can cause sterility and liver, lung and kidney problems; phenol, which is a neurotoxin and can cause kidney and liver damage; and methanol.

5. SENECA SAWMILL CO.,SENECA SUSTAINABLE ENERGY

90201 Highway 99 N.

Nearby: The closest home is 1,500 feet away. Irving Elementary is 1.5 miles away, Spring Creek Elementary is 1.9 miles away and Willamette High School is 2.4 miles south.

Emissions: The sawmill and the biomass plant are connected but have different LRAPA permits. The sawmill emits 73,000 pounds of air toxics and the biomass plant 17,900 pounds, according to Beyond Toxics.

Effects: The plant emits significant amounts of carbon and nitrogen oxide. Beyond Toxics reports the top three chemicals at the plant are acrolein, which is associated with respiratory congestion, and eye nose and throat irritation; styrene, associated with increased risk of leukemia and lymphoma, and with liver, kidney and eye and nasal irritation; and formaldehyde.

6. STATES INDUSTRIES

(Hardwood panel products)

29545 East Enid Road

Emissions: 42,800 of air toxics according to LRAPA data.

Effects: Acetone can cause kidney damage, breathing problems and low blood pressure; cumene is a carcinogen that can cause skin rash and reproductive problems; and methanol.

7. MCFARLAND CASCADE

90049 Hwy 99 N.

Emissions: EPA’s TRI reports 209 pounds of pentacholorphenol. LRAPA reports 40,734 pounds of air toxics.

Effects: Hexachlorobenzene can cause neurological, teratogenic, liver and immune system effects; dioxin can impair the immune system, the developing nervous system, the endocrine system and reproductive functions; and pentachlorophenol.

8. FLAKEBOARD AMERICA, INC.

50 N. Danebo Ave.

Nearby: Sunshine Preschool is .7 miles away; Danebo Elementary,

1.1 miles; and Kalapuya High School .9 miles. The nearest home is

500 feet.

Emissions: EPA’s TRI database shows 112,530 pounds of air toxics, including methanol and the LRAPA permit shows 220,800 pounds of air toxics.

Effects: The chemicals have included methanol, formaldehyde and ammonia. Flakeboard America has reduced its formaldehyde emissions, and the company says it doesn’t necessarily emit to the maximum levels in its permit.

Comment from Flakeboard

Full comments from Flakeboard President and CEO Kelly Shotbolt on the question of if Flakeboard America is emitting formaldehyde. The TRI database did not list the chemical, but the LRAPA permit does.

Thank you for the opportunity to comment. As background information, an MDF mill such as the one we operate in Eugene, is essentially a large recycling facility. We take biomass residuals from surrounding wood product facilities that historically have been landfilled or burned, and produce composite panels that are typically used in the furniture, molding, and cabinet industries. Our products have been Eco-Certified by the Composite Panel Association and are classified as carbon neutral or better (our products are in fact carbon negative).

When converting biomass to MDF products, our process does create some level of the emissions you cited in your email. You have correctly stated the levels we are permitted by the Lane Regional Air Pollution Authority to emit. It is important to understand however that we don’t necessarily emit to these maximum levels. Over the years, Flakeboard has taken steps to reduce emissions with the installation of a bio-filter and proprietary resin application technology.

One other thing we would like to point out when an emission level is discussed, is that overall, we are a small contributor for most of them. If for instance you are just considering West Eugene, the Lane Regional Air Pollution Authority (LRAPA) has estimated that the Wood Product sector contributes less than 1 percent of formaldehyde in the Bethel area. Our site would only be some portion of that small number. In fact, on this particular item — wildfires, residential energy usage, and mobile sources such cars, trucks, buses, railroad, airplanes, lawnmowers etc. — combine to contribute approximately 95 percent of the total formaldehyde. You can obtain more detailed information about emissions and EPA’s NATA screening tool directly from LRAPA.

At Flakeboard, we are extremely committed to regulatory compliance and overall environmental stewardship. We thank you for taking the time to communicate with us on this issue.