Mick Garvin lay calmly on his side while three tons of steel heaved toward him. It was the morning of Sept. 10, 1995, and the sun hadn’t yet hit the north face of the mountain. The air was chilly on Garvin’s face, his right hand cold against a steel chain. He was locked intothe gravel road.

Jake Ferguson and two others sat stoically in front of Garvin, forming a soft barrier between the human lock-down and the machine, while another dozen forest activists rubbed the sleep out of their eyes and gathered around. Independent filmmaker Tim Lewis circled the scene with his video camera, and resident pikas, tiny bunny-like mammals with long whiskers, scurried under boulders and squeaked. The Forest Service road grader heaved closer, knocking away a large rock and rising up with a moan. The blade stopped about 10 feet from Ferguson’s military boots.

Garvin looked at the backs of the heads protecting him, gazed up at a snaggly old Doug fir and felt a warm wave of gratefulness. The 37-year-old had been doing forest defense work for years, but never before had he seen activists hold their ground like this. A state trooper summarily informed them that they could be arrested, and a Forest Service officer turned to Garvin. “Are you going to leave?”

“No.” And she couldn’t make him. He was locked into a “Sleeping Dragon,” a concrete-reinforced 55-gallon drum buried in the road and covered with a metal fire door. Garvin’s arm ran through a hole in the door and down a pipe into the drum; his chained wrist was clipped to a pin at the bottom. The road grader couldn’t proceed without rolling over him, and he wasn’t about to budge.

Secretly, Garvin hoped the standoff wouldn’t last much longer. Fluid was collecting in his hand, making it swell, and if his fingers fell asleep he wouldn’t be able to open the clip to get out. But if the grader got past him it would roll toward Bunchgrass Ridge, where ancient trees were slated for sawing; he was willing to risk his life to prevent that. Garvin settled against the cold metal door and rolled a cigarette.

Finally, the road grader made a clumsy retreat down the mountain. And in the seasons that passed before Forest Service vehicles again tried to cross that line, the rag-tag road blockade became one of the longest-running acts of civil disobedience in U.S. environmental history. It also brought together a small crew of eco-anarchists who would later develop bigger, more explosive plans.

One autumn afternoon four years earlier, humans had crept into this corner of Willamette National Forest. They slipped past towering fir trees dry from a long summer drought, placing incendiary devices at the border of a roadless area set aside as endangered spotted owl habitat. The flame grew into a torrent of fire that swept through 9,200 acres— a third the area of Eugene — over the next two weeks. The Forest Service spent $10 million battling the blaze before snow finally put it out.

Forest Service investigators never caught the arsonists who sparked the Warner Creek Fire, but to environmentalists the motive was obvious. They strongly suspected timber industry insiders hungry for access to protected old-growth or even Forest Service firefighters looking for work. Such arsons had become a pattern in the West, in keeping with the Forest Service adage: “The blacker the forest, the greener the paycheck.”

In Eugene, UO doctoral student Tim Ingalsbee was itching to help. He’d fought fire with the Forest Service every summer for years, but had hung up his hard hat in 1990 after concluding that fire suppression throws forest ecosystems off their natural rhythms. Now, as the agency batted about plans to cut down old-growth trees in the name of fire safety, the 30-year-old environmentalist saw a chance to redeem himself. “All those years fighting fire — I could pay back that bad karma with good works defending this place from salvage logging,” he reasoned.

In November 1991, Ingalsbee hopped on a Forest Service tour bus to check out the still-smoldering forest. There he met Catia Juliana, a bright-eyed woman who was monitoring logging projects for Southern Willamette Earth First!, an eco-radical group with a bent towardmonkeywrenching. By the next spring Ingalsbee and Juliana had formed a sister group, Cascadia Earth First!, and walked every foot of the burn. Their masterpiece, Alternative EF in the Forest Service’s draft environmental analysis, supposedly stood for “ecology of fire” — but secretly represented Earth First!. “The symbolism went right by them,” Ingalsbee said. “I took the pleasure of seeing ‘EF’ 400 times in the final document. We fantasized about hacking into their computer and adding the exclamation points.”

Willamette National Forest Supervisor Darrell Kenops didn’t go for it, instead deciding in October 1992 to “salvage” log 40 million board feet of timber from the burn. Outraged Earth First!ers performed a Halloween skit in front of Kenops’ office, depicting the salvage proponents as monsters on trial before Mother Nature. Local media ate it up, and an unprecedented 2,300 citizens sent comments to the Forest Service opposing the Warner Creek logging plans. When that didn’t work, Ingalsbee tried a new line of defense, founding the Cascadia Fire Ecology Project to educate the public on the science of burned forests. As the instructor of a popular UO class called Envisioning Ecotopian Communities, he also quietly inspired dozens of students to join the cause.

For a moment in the summer of 1995, Ingalsbee’s fight appeared to be over. U.S. Magistrate Thomas Coffin had struck down the Forest Service’s salvage plan on the grounds that it illegally rewarded arson; the ruling just needed a signature from Judge Michael Hogan. But Hogan stalled long enough for Congress to pass a salvage rider that opened the Warner Creek burn and thousands of other forests to expanded logging.

On Sept. 6, when Hogan declared Coffin’s ruling moot, Cascadia Earth First!ers were ready to execute Plan EF!. “They left the courtroom and went straight up the mountain,” Ingalsbee said. “They sat in the widest, levelest part, which was the logging road, and they kept vigil 24-7.”

The buzz spread quickly in eco-radical circles, attracting a core group of activists to Eugene. Among the first was Tim Ream, who’d heard about the Warner Creek campaign at an Earth First! gathering outside Arcata, Calif. When he hiked into the charred Cascadian forest, where spotted owl pairs had returned to fledge their young, he made a personal vow to defend it.

Ream linked up with Tim Lewis, a lanky 40-year-old filmmaker who’d joined a 33-mile march into the Warner Creek Fire area. When Lewis saw the passion on Forest Service Road 2408 — activists pickaxing the dirt, their hands blistered, standing firm against the “freddies,” as they called law enforcement — he knew he had his next film project. His footage of the blockade, narrated by Ream, would become the documentary Pickaxe.

UO student Jeff Hogg, an Earth First! activist who had taken Ingalsbee’s class, began supporting the campaign through the Survival Center, a campus organization dedicated to social and environmental activism. So did Lacey Phillabaum, an art history major who reported for the radical campus newspaper The Insurgent. Fellow Insurgent reporter James Johnston, who she was dating, also lined up for the cause. Cecilia Story, a graphic designer from Colorado, joined a march into the forest and was hooked the moment she saw the ancient, lichen-draped trees slated for cutting. “My heart just broke,” she said. All four were in their early twenties.

Meanwhile, the four co-editors of the Earth First! Journal unapologetically trumpeted the blockade. One of those editors, Jim Flynn, had moved with the magazine to Eugene in 1993, establishing its headquarters in a tucked-away green ranch in Glenwood. Journal volunteers Stella-Lee Anderson and her boyfriend Kevin Tubbs, both in their mid-twenties, helped set up the first camp.

A hardass drifter with a criminal past, Jake Ferguson, tattooed and camo-clad, with long brown dreadlocks whose natty ends looked like they’d been dipped in peroxide, showed up ready to do something meaningful. Guarded, somber and glassy-eyed, he seemed to be either on hard drugs or in the first stages of recovery. Not the type to talk about hippie shit like magic and rainbows, Ferguson wanted a revolution and stuck at the camp longer than anyone else. “He was committed to something for awhile,” Anderson reflected. “Warner Creek was healing for him. A time to start anew.”

Today, some Warner Creek veterans reserve the worst kind of nouns for Ferguson: snitch, sociopath, loser, pyromaniac, junkie. They’re disgusted with him for ratting out fellow forest defenders for crimes committed in later years. But others, especially the staunchly nonviolent Ingalsbee, would be most appalled by what the defendants had allegedly done.

Glasses askew and dark curls wet with sweat, Tubbs grappled with a boulder the size of a small child. He’d been working Road 2408 with the activists for days, pickaxing a 10-foot-wide, 15-foot-deep trench — big enough to fit a school bus in. The boulder would be another obstacle to keep out vehicle-bound loggers and freddies.

Behind the trench line and out of police reach, a new kind of freedom took root. The eco-rads erected two tarp-covered teepees, one for sleeping and the other for cooking. They rigged a fort complete with a drawbridge using downed logs left by loggers and built two video platforms in trees, from which they could survey the freddies and scope the surrounding clearcut-scarred hills.

The activists began to lose their identities as Americans and pledge their allegiance to Cascadia — their bioregion, home of the ancient pines and dizzying stars, wherein all people could become wild again. They dubbed the blockade Cascadia Free State and themselves Cascadia Forest Defenders, adopting nature-inspired aliases like Lupine, the Dog and Madrone.

And they made love, as free wild creatures do. The couples let the fecundity of the forest sluice into their relationships, while the single activists flirted and hooked up. Juliana realized she was pregnant while hiking near Kelsey Creek, a bubbling blue salve in the Warner Creek burn.

“Love in the barricades — how can you get more romantic?” Ingalsbee recalled with a grin, sitting in a Eugene café while the rain drizzled outside. His and Juliana’s daughter, Kelsey, is now 10.

Of course, some moments of the blockade sucked: the weeks of nonstop rain, the blizzards, the days when stale bagels were dinner. “It was just like any summer camp, where there were long periods of boredom,” remembered Johnston, now a clean-cut policy analyst for Forest Service Employees for Environmental Ethics.

But even in those soggy times, a sense of common purpose kept the forest defenders going. They agreed by concensus not to do anything to scare off public support, like hurt a freddy or blow something up. The unspoken line was somewhere near petty vandalism: picking the trench in the road, even throwing buckets of shit at the Oakridge ranger station under cover of night. “Violence would take away from what we were doing,” Anderson explained, “and property destruction was distracting from the goal in mind.”

So the activists got creative, making a perilous wager that loggers and Forest Service agents would value human lives more than those of trees and animals. They pinned themselves under parked cars, locked their arms into concrete-filled barrels, fastened their necks to the backs of logging trucks. Tubbs helped build a “bipod,” a platform propped on two poles as tall as a ranch-size house and counterbalanced by cables anchored to the road. If a freddy even nudged the structure, the activist on the platform could come crashing down.

“At the time, yeah, I was scared,” Johnston said. “The stuff that we were doing was not safe.” But in the course of the blockade, no one was seriously hurt.

This brand of forest defense, aka “Warnerization,” was catching on. Eco-radicals learned to climb trees, tie knots and generally piss off authorities at “action camps” across the West. Oregon activists confronted logging operations in the coast range and southwest Siskiyous while interstate eco-rads set up blockades in Idaho, Colorado and Montana. Their commitment to peaceful civil disobedience drew supporters of diverse ages and backgrounds, even inspiring one former Indiana congressman to get himself arrested.

But the escalation of forest activism also produced a backlash, particularly among people dependent on timber money. One logger threatened to fell a tree on the forest defenders while they begged him to spare the old growth. Forest staff allegedly cut the cable on Tubbs’ bipod one night while it was unmanned, and drunken men from the nearby town of Oakridge drove up to the trench line to talk belligerent smack.

Forest Service officials generally left Cascadia Free State alone, but they were uneasy. “It’s more difficult for officers than people think,” said Forest Service Special Agent Sher Jennings, who was assigned to monitor the Warner Creek campaign in its last season. “They’re trying to do what they think is right, and they don’t want anyone to get hurt. It can get pretty trying.”

Although one reporter suggested that the Cascadia Forest Defenders may be domestic terrorists, the notion didn’t stick. Front-page stories in The New York Times and The Washington Post depicted peaceful eco-radicals taking a stand for the forest, and Cascadia Free State attracted hundreds of visitors, including a bus full of Vermont schoolchildren and the president of The Audubon Society.

The campaign pressed on in the city as in the forest. Supporters in Eugene’s bohemian Whiteaker neighborhood collected food and supplies for the camp, while mainstream environmentalists kept up pressure on the Clinton administration. The four EF!J co-editors, who later included Phillabaum, cranked out copy in Glenwood, spreading Warner Creek news to eco-radicals across the nation.

Tim Ream staged a hunger strike on the cold concrete plaza of the downtown Federal Building, consuming nothing but juice and vegetable broth throughout the cold and rainy autumn. “Frat boys and angry timber people” would sometimes threaten him, Ream said, but others brought talismans and prayers. On the 70th day he flew to Washington D.C. to lobby Congress, returning to Eugene to break his fast five days later. On the last night of the strike Ream’s supporters fasted with him, pitching more than 20 tents on the Federal Building plaza.

Winter came upon Cascadia Free State fast and cold, sinking the teepees deep in snow. But even as their numbers dropped, the activists kept vigil, gnawing on stale bread and making music around a wood stove. Supporters lugged food and supplies five miles uphill in snowshoes, scanning for the Earth-emblazoned flag that flew above the fort. Sometimes they heard coyote-like yet distinctly human howls floating out of the woods: Aw-oooooo!

In July 1996, on the one-year anniversary of the salvage rider’s passage, Portland musician Casey Neil sang “Dancing on the Ruins of Multinational Corporations” while eco-radicals danced barefoot on the Federal Building lawn. Then Phillabaum, ponytailed and hairy-pitted in a blue sundress, took the mike.

She told the crowd about the “magic” she’d discovered at Warner Creek: cotton-cloud sunrises and mesmerizing moons, wild irises and cold mists blowing off waterfalls, a balmy June night when she hiked naked with other women and heard a spotted owl hoot for the first time. “It feels right,” she said.

Ten years later, many in that crowd would see her as a traitor.

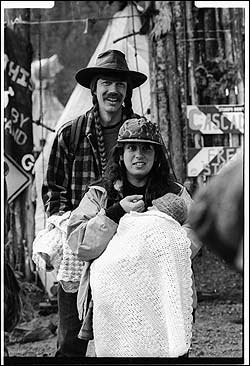

About 100 eco-rads, clad in camos and muddy dresses, made a wide circle in a sunny forest clearing. Ingalsbee and Juliana grinned as they stepped down the grassy aisle, newborn Kelsey in the bride’s arms, while the wedding guests sang “Give Yourself to Love.”

The couple wore green garlands: Ingalsbee’s atop two long, sandy braids, Juliana’s on a cascade of wavy brown. The officiator, a maternal-looking woman in a flowy dress, clipped together the chains encircling the bride and groom’s wrists, locking them in an Earth First! handfast — “so the freddies won’t rip us apart,” Ingalsbee said. Then newlyweds and guests made a vow together: “From this day forward, I will commit myself to respect and defend all things wild and freeeeee!”

They’d barely finished when a short woman with brown dreadlocks stepped forward. People were still needed at the blockade, she announced rather sternly. The fight to save Warner Creek wasn’t over yet.

Two weeks later, on Aug. 16, 1996, Anderson was ambling in the woods when an urgent message crackled through her walkie-talkie: A bulldozer was headed down Road 2408. She made a dash for the blockade, scrambling up hills strewn with rhododendrons and laurels, and thrust her hand into a pile of rocks in the road, a faux lockdown. Three other women were already secured EF! style, their arms stuck into concrete-filled barrels.

The officers told the activists that their year-long vigil was over: The Clinton administration had bowed to public pressure and backed away from hundreds of controversial logging projects, including Warner Creek. But without proof on paper, the women wouldn’t budge. They thought it was a trick.

Forest Service agent Jennings, for one, was worried: She claimed that there was a fire in another part of the forest, and firefighters could only reach it via Road 2408. “We had a pretty high sense of urgency,” she recalled by phone from her current office in Seattle. “However long they wanted to lie there, we had to get around them. And we couldn’t get around them without taking out an old growth tree.”

While a bulldozer tore down Cascadia Free State, Forest Service officials removed the activists from their lockdowns and arrested them. Jennings also arrested two Register-Guard reporters who had come to cover the raid, seizing their film and notes.

Three days later, an elfin man dressed like a tree hyped up a crowd of supporters in downtown Eugene. The activists were thrilled about the logging project’s cancellation but pissed about the raid; they wanted to show solidarity with the four arrested activists. “Free the Warner women!” they chanted, marching en masse to the jail, which shared walls with the court. When they arrived at the security checkpoint and an officer informed Ream that only one person would be allowed in for the arraignment, Ream turned to the crowd. “How many of you think that you are the one?” he shouted.

Hoots all around. The eco-rads erupted into a chant of “No justice, no peace,” Phillabaum straining so hard that a blue vein popped out in her neck. Some of the protesters started banging on the metal detector and then walked right through.

It was on. Someone pulled out a harmonica; others started drumming, jumping and chanting “Cascadia Free State!” as if they were still in the woods instead of a jailhouse lobby. An officer stepped into the fray and swayed around like a buoy in rough waves. Some protesters, sensing the danger here, started up a new plea: “No violence!” It wasn’t clear whether they were addressing the officials or their fellow protesters.

And then, as quickly as it had churned up, the protest calmed. The activists sat on the ground and locked elbows. Police began the arduous task of detaching them one by one, dragging limp bodies into the jail, sometimes by the hair. A new chant rose: “Arrest them; don’t beat them up!” Protesters grabbed at the heels of their detached comrades and reached for last-minute kisses, shrieking and crying. A single tear ran down the cheek of a young male officer standing guard.

Inside the jail, the activists refused to identify themselves or their friends. They dead-weighted when jail staff tried to move them; they wouldn’t eat or sign papers. Eventually the guards threw them into big holding cells, one for the men and one for the women. The women out-sang the men, having a broader repertoire, but the men wrote a new song and smuggled it out on paper plates.

Within five days all of the activists were released. The “Warner women” were convicted of misdemeanors, later downgraded to violations, and the jailhouse protesters for criminal trespass. A year of rough forest living, perilous protests, heavy campaigning, mass arrests and constant vigilence had frayed many nerves, but they’d done it: They’d saved Warner Creek.

The forest defenders rode that wave of euphoria into urban Eugene, where many would rent cheap warehouses and keep the activist flame burning. “When people came down from Warner Creek as victors, there was a lot of power there,” Lewis said. “And that power came down on Whiteaker.”

The fire would only burn hotter.

In a high-profile sweep that began on Dec. 7, 2005 and continues into the present, the federal government indicted 18 people for a spate of environmentally motivated sabotage crimes committed in the West between 1996 and 2001. No one was physically hurt in the actions, mainly arsons against corporate and government targets perceived to be destroying the planet. Yet the FBI is calling the defendants “eco-terrorists” and seeking particularly stiff sentences for the five remaining non-cooperators, whose trials are pending. Eight defendants have pled guilty, four are fugitives and one committed suicide in jail.

Segments of the American public have glanced at the mug shots inked into newspapers and seen dangerous eco-fanatics who belong behind bars. But here in Eugene, where most of the alleged saboteurs have lived, those faces are familiar to hundreds and dear to many. In recent months, EW spoke with more than a dozen local people who described the accused as compassionate, Earth-loving people, influenced by a time that also shaped Eugene.

Five years after the last act of arson, the so-called Operation Backfire arrests have sparked the national media’s curiosity. That attention, beaming like a headlight through a fog of paranoia, tends to obscure the other regrowth that sprouted from the ashes of Eugene’s eco-radical era.

This five-part series attempts to tell that story.

Part II: Eco-Anarchy Rising

https://eugeneweekly.com/2006/11/09/news1

Part. III: Eco-Anarchy Imploding

https://eugeneweekly.com/2006/11/22/coverstory

Part IV: The Bust

https://eugeneweekly.com/2006/12/07/news1.html

Part V: The Ashes