White powder exploded onto Randy Shadowalker’s chest and face. He couldn’t breathe; his throat and lungs felt like they’d been set on fire from the inside. The 31-year-old eco-activist fell to the ground, clutching a maple branch in his hand, only to be roughly ordered back up by the policeman who had shot him with tear gas powder. Coughing and drooling and dripping snot, he struggled to his feet and staggered through a cloud of tear gas, the cop shoving his bony body from behind.

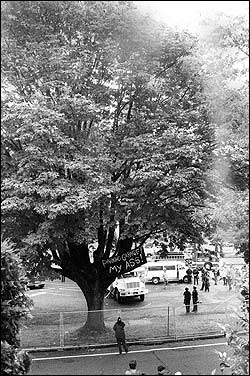

It was the morning of June 1, 1997, and hundreds of Eugene citizens had gathered downtown to witness the cutting of 40 large trees to make way for a parking garage. Inside the fenced-off lot, Earth First!ers and Cascadia Forest Defenders perched in doomed trees: sweet gum, bigleaf maple, black walnut, redwood. While the cops outside the fence pushed back the crowd, those inside plucked the protesters out of the trees with a fire truck lift, blinding them with pepper spray. Down came Lacey Phillabaum, Jeff Hogg, Mick Garvin, Josh Laughlin and others. A logger followed the fire truck, cutting each tree after its occupant descended.

Jim Flynn, about 30 feet high in an old sweet gum, was the last one left. A fireman and two police officers emptied about a dozen canisters of pepper spray on him in roughly an hour, twisting his foot, pulling his hair, cutting his pants to spray his bare leg. When he finally came down, Flynn peeled off his chemical-drenched clothes and stood with his arms outstretched as the cops blasted his body with a fire hose. The water just spread the burning oil; every inch of his skin was on fire.

Tim Lewis peered at the scene through a video camera, digging Flynn’s Jesus Christ-like pose. He would air this footage on Cascadia Alive!, a public access TV show that he and fellow activist Tim Ream had started up 10 months ago, in the last weeks of the Warner Creek road blockade. The eco-radicals would gain some major public sympathy points from the protest — and the city would think twice before taking out a swath of old trees again.

Cascadia had brought its act to town.

Whiteaker in late 1997 was a hot hash of radicals. There were the forest defenders, mostly twenty- and thirtysomething hippies high on the victory of Warner Creek; the gutter punk anarchists, who rocked out on loud music and white drugs; and the resident artists, who’d been coloring up the neighborhood for years. Icky’s Teahouse, a grimy free-for-all joint on Third and Blair, was a hangout of choice for all three.

It was a time of intense community-building for the eco-anarchists, who roved between neighborhood hot spots like Tiny Tavern, Out of the Fog café, Scobert Park and a crop of housing co-ops. Warner Creek vet Stella-Lee Anderson launched the Jawbreaker gallery to showcase neighborhood creations, and artist Kari Johnson painted post-apocalyptic feminist visions on Whiteaker walls. Johnson led eco-activists to tear up a parking space and turn it into a community garden — Joni Mitchell’s dystopic vision in reverse — while Critical Mass bikers, empowered by their numbers, reclaimed the streets from cars. Activists shared knowledge at “Free Schools” and guerrilla info shops, neighbors swapped clothes at a community free space and Food Not Bombs brought free vegetarian meals to local parks daily.

“I think everybody had their own vision of what was going on,” Johnson said, “but what I saw tying it all together was making an alternative to hierarchical, capitalist society, and trying to have a communalist ethic.”

As the community knit itself tighter, independent media projects beamed Whiteaker’s energy out to the world. Eco-radicals including Tim Lewis, Cindy Noblitt, Randy Shadowalker and Robin “Rotten” Terranova produced the weekly live TV show Cascadia Alive!, featuring a hodgepodge of guest ranters, musical acts, indie activist footage and call-in segments. The show also aired footage from local CopWatch activists — namely Lewis, James Johnston and Kookie-Steve Heslin — who dogged Eugene police with their video cameras.

“Cascadia Alive! was really putting grease on the fire of the activist scene,” Shadowalker said. “People started coming to us for news. The local media feared us; the cops feared us. But every time they tried to mess with us, it just grew the army of resistance.”

That surge of creative, autonomous energy attracted fresh new blood to town, eco-anarchists ready for action. They’d heat up not only the streets of Eugene but also the surrounding forests, staging direct actions and road blockades that would make Warner Creek seem vanilla by comparison.

The activists worked busily in the rosy light of a May 1997 dawn, stringing two ropes across a highway near Detroit, Ore. — one roughly 3 feet off the road and the other about 75 feet high. The structure was designed so that if a vehicle hit the low rope, two women dangling in harnesses from the high rope would fall. They were protesting the Sphinx logging project in the Santiam watershed.

Right before they finished setting up, the lookouts down the road started screaming. A truck was rolling down the highway, and it didn’t show signs of stopping. When it came within 70 feet of the rope, Shannon Wilson — a determined forest defender who had been a core part of the Warner Creek blockade — stood in its path. The truck slowed to about 5 miles per hour and swerved around him, coming so close that he was able to smack its headlight, and finally stopped. The shaken activists lowered the women to safety, gathered their gear and split.

“I didn’t see a lot of those people after that,” Wilson said. “They were too scared to do anything. It basically killed the campaign.”

Lacey Phillabaum would remember that near-fatal moment in a Nov.-Dec. 1998 Earth First! Journal editorial: “I have seen an activist come nose to grill with a Mack truck at a protest and believed for an endless moment that the trucker would not stop.” An activist had recently been killed by a logger in California, and Phillabaum was beginning to question the “cultural promise” of civil disobedience: that if eco-activists nonviolently laid their bodies on the line, no one would willingly harm them.

Fear of injury hadn’t slowed the Cascadia Forest Defenders, who harnessed the Warner Creek energy to protest a string of timber sales in the late ’90s, their names Oregonian poetry: First and Last, Horse Byars, Red 90, Olalla Wildcat, China Left, Winberry, Growl & Howl. They’d saved some trees and mourned the rest.

But none of those campaigns stand out like the Fall Creek blockade, launched in spring 1998 to stop the Clark timber sale in Willamette National Forest. The dominant crew at the camp was a group of crusty, itinerant punks in their teens and early twenties, some of them happy just to have a free crash-pad and food. Others, however, were experienced activists out to save trees by any means necessary.

The Fall Creek tree-sitters generally rejected the unspoken code of nonviolence that had guided the Warner Creek campaign just a few years earlier. They fought with Forest Service officers (or “freddies,” as they called them), pissed on them from the trees, even staged a fake hanging to freak them out. Some of the punks trashed the camp, letting their dogs fight and hump and tear up the forest understory. Tree-dwelling flying squirrels burrowed into their sleeping bags, ransacked their food and fell into their compost buckets. At times the activists got dangerously drunk hundreds of feet off the ground, and once a propane tank blew up in a tree-sit.

Earth First!ers and Cascadia Forest Defenders, sensing the hard edge, generally distanced themselves from the campaign while still supporting it with food and supplies. The tree-sitters were, after all, braving freddies and foul weather to keep chainsaws out of the forest. Dubbing their camp Red Cloud Thunder Free State, the Fall Creek tree-sitters embraced their role as the outcasts of the Earth First! movement, viewing themselves as the real revolutionaries — the ones who were ready to push beyond civil disobedience.

As punks defended the forest and eco-anarchists rollicked in Whiteaker, the Eugene-based Earth First! Journal editors — including Jim Flynn and Lacey Phillabaum — put the local movement into a larger context. They gathered news of civil disobedience and eco-sabotage actions in Europe, South America, Asia and all over the U.S., examining the intersections of labor, civil rights and anti-consumerism movements. Earth First! was growing, if painfully.

The EF!J ran a feature called “Earth Night News,” which announced sabotage actions claimed by the Earth Liberation Front and other covert actors. ELF had been conceived in England in 1992, when eco-activists decided to sever controversial sabotage actions from the civil disobedience-oriented Earth First!. The Sept.-Oct. 1993 EF!J introduced ELF as “a movement of independently operating eco-saboteurs.”

Earth Night actions spanned the globe, but in the late 90’s an especially methodical cluster struck the Pacific Northwest. It began on Oct. 28, 1996, when arsonists torched a Forest Service pickup truck in Detroit, Ore. They also attempted to burn down the ranger station, but the fuel-filled plastic jug on the roof didn’t ignite. Spray-painted on the building was a tag American police hadn’t seen before: “ELF.”

Only two days later, arson struck the Forest Service ranger station in Oakridge, Ore. The building burned from the four corners into the middle — seemingly a professional job. The father of the Warner Creek campaign, Tim Ingalsbee, was crushed: years of his documentation of the Warner Creek Fire had been in that building.

Arsons followed at several BLM wild horse corrals, a slaughterhouse, a wildlife research station, a Vail ski resort, a forestry office in Medford, a meat company in Eugene. No one was hurt in any of the actions, but communiqués condemned the targets as “Earth-rapers” who deserved what they got.

The EF!J also ran “Dear Ned Ludd” columns, which offered detailed tips for carrying out sabotage actions like tree-spiking, electrical tower blow-outs and arsons with time-delayed fire-starters. A disclaimer noted that EF! didn’t necessarily endorse such enterprises, but the journal’s overall tone was supportive.

Ingalsbee argued with the EF!J editors about celebrating arson. “Fire is a mystical force that you release; you better be prepared to deal with the consequences,” he said. “You set up other humans to come attack you.” But many of the journal’s contributors defended ecotage, viewing property destruction as a wake-up call to the self-obliterating masses.

Phillabaum grew weary of so much debate and so little action, and after three years she left the journal, publishing her official sign-off in the March-April 1999 issue. “I’ve found and discarded all sorts of different visions of this movement, seeing us as everything from nonviolent revolutionaries to disgruntled, dysfunctional outcasts … [but] I think the depth of our passion and the sincerity of our commitment is what distinguishes Earth First!,” she wrote. “I look forward to seeing you again soon — on the frontlines.”

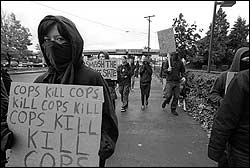

The concept of righteous sabotage was blowing up among Eugene’s most hard-core eco-anarchists and their out-of-town allies, who staged increasingly bolder riots: throwing bricks through banks and McDonald’s joints, trashing the Nike store on 5th Avenue, lighting fires in Dumpsters and setting up confrontations with police.

Disrupting traffic and smashing property were sure-fire ways to bring the cops; the media would invariably follow, providing the anarchists with free press. Some of the rioters would wear Zapatista-inspired bandanas which, besides obscuring their identities in front of police cameras, told the world that at least some Americans were ready for revolution. “Global capitalism is everybody’s problem, and nobody’s doing anything about it,” reasoned activist Chris Calef. “If it’s violence and mayhem [that bring attention to the issues], then fuck it.”

EPD Detective Bob Holland remembered those days as tense. “We saw a huge influx of out-of-town anarchist types: real scary, hard-core, punk-lookin’ people who were clearly not from Eugene,” he said. “There was all this tension going on in the Northwest, and here in Eugene we seemed to be at the epicenter.”

The police weren’t the only ones to take on the punks. Whiteaker vigilante Dennis Ramsey, a self-described ex-anarchist then in his mid-40s, viewed the eco-anarchists as “organized mayhem in the guise of liberty” who were trashing the neighborhood. He and others convinced the landlord of Icky’s Teahouse not to renew its lease, shutting it down in the summer of 1997. Ramsey then turned to the task of cleaning up Scobert Park, which he saw as a drug-infested “crime magnet,” and joined a successful neighborhood push to temporarily close it. Eco-anarchists responded by setting up tents and occupying the park.

Vandals targeted the Red Barn, a local natural food store then owned by Ramsey’s former girlfriend. “I let [the anarchists] know, eye to eye, that if they pulled that shit on me I would murder them in the streets,” Ramsey said. “For the first time in my life, I had to carry a concealed weapon.”

As riots became more regular in Whiteaker, black-clad badasses began to bait law enforcement. “People were very empowered,” activist James Johnston explained. “We were gonna fight the police.” And the CopWatch activists would videotape it.

“We kept on seeing night after night the Tim Lewis stuff [on Cascadia Alive!],” EPD Detective Holland said. “The way it was cut and edited, we were like ‘Wait a minute. It didn’t happen that way.’ So we started our own video unit.” Holland and Lewis had a few silent confrontations at protests, each man videotaping the other.

The cat-and-mouse game would take a grave turn on June 18, 1999, during what started out as an anti-globalization event. The leaders of the industrialized world were meeting in Cologne, Germany, and activists planned protests in 160 cities. Local organizers had notified the EPD ahead of time, promising to be peaceful; in response, police scaled back their planned presence and closed off Willamette Street.

Hundreds of people showed up, reveling in the joy of smashing VCRs and computers in the street. Soon the protesters began roving, looking for nefarious corporations to target. Some rioters started jumping on cars and breaking windows of businesses they deemed evil — a bank, a furniture store, Taco Bell. A few looted 7-Eleven and brought out beer for the hot and hungry crowd. “People felt like the energy was there to crack the system, find the break in the dam, start a revolution,” Lewis said.

About four hours into the riot police confronted the protesters at Washington-Jefferson Park, shooting tear gas powder at them — but the wind blew back toward the police. “After a few minutes the cops were just wandering around in a cloud of tear gas,” said Rob Thaxton, an anarchist who was at the scene. “People started throwing rocks and other things at them.”

A group of more than 100 rioters ditched the police and roved on for several more hours, looping between downtown and Whiteaker. They figured that as long as they stayed together the cops couldn’t mess with them, but if they split up they’d be arrested. When they reached 7th Avenue and Jefferson Street, police made their move, throwing the rioters to the ground, pepper-spraying and arresting them.

Thaxton stood there and watched, furious, then picked up a big landscaping rock with plans to smash it through a squad car window. When a cop came running toward him, Thaxton threw the rock at the cop “to try to deter him.” He was arrested and sentenced to seven years in prison for assault with a deadly weapon.

The police, for their part, had learned a lesson: to increase their “stand-by” presence at all rallies, even the ones that were supposed to be peaceful. “We met people halfway on this one and got burned really badly,” EPD’s Holland said. “That really influenced the way things happened later on. It just seemed like the anarchist community was ready to go to war with the cops.”

In a sense, they were. The eco-anarchist community had built up its power like tinder in the streets of Whiteaker, with the ambitious goal of snapping Americans out of their destructive, consumptive, self-imprisoning cycles. They wanted to ignite a revolution.

Soon, the world would notice.

Part I: In Defense of Cascadia

https://eugeneweekly.com/2006/11/02/coverstory

Part. III: Eco-Anarchy Imploding

https://eugeneweekly.com/2006/11/22/coverstory

Part IV: The Bust

https://eugeneweekly.com/2006/12/07/news1.html

Part V: The Ashes