Kari Johnson surveyed the chaos through a pair of swim goggles, a bandana over her nose and mouth to filter the tear gas, and steered her partner, Randy Shadowalker, through the teeming streets of downtown Seattle. He peered through the lens of a small hand-held video camera, recording the Nov. 30, 1999 protests against the World Trade Organization.

An estimated 50,000 people had descended on the city to resist a global economy that, from their perspective, treated workers, nature and consumers as mere cogs in a money-making machine. A small group of those protesters, mostly darkly clad young anarchists known as “the black bloc,” destroyed the property of corporations that they felt represented the evils of globalized capitalism.

What Johnson witnessed remains etched in her memory seven years later: A mainstream news van with its tires slashed, its metal body covered with graffiti. The smashed-in window of a jewelry store, its alarm blaring, its diamonds exposed. A man splayed spider-like on the wall of a corporate shoe store, bear-hugging the letters one at a time — N, I, K, E — then ripping them off and tossing them down to a cheering crowd.

Johnson periodically shuttled Shadowalker’s tapes to Tim Lewis and Tim Ream, charismatic activists who’d been stirring up the anarchist scene in Eugene. The two Tims spent the night of Nov. 30 in a Seattle editing studio, jacked up on adrenaline as they cobbled together a 35-minute video called RIP WTO N30. By 2 pm the next day they were selling the film, a choppy but intense sampling of the heaviest day of WTO protests — most of it recorded by Lewis himself — at five bucks each in the streets. From there, it would make its way to news outlets throughout the world.

Maybe media took their cue from Seattle Police Chief Norm Stamper, who publicly blamed the property destruction on Eugene anarchists just days before resigning, or from Eugene Mayor Jim Torrey, who lamented to reporters that Eugene was “the anarchist capital of the United States.”

Whatever the reason, it seemed that national media had made their collective decision: Eugene anarchists were responsible for vandalizing downtown Seattle, provoking police to assault nonviolent protesters and paralyzing the WTO convention. Reporters for 60 Minutes, Harper’s and Rolling Stone swooped on this small city, inviting the notorious anarchists to explain their behavior at the Battle of Seattle.

And while a few loud-mouthed, hard-talking men stepped up to the task — most dominantly Tim Lewis, Tim Ream, John Zerzan, Robin Terranova and Marshall Kirkpatrick — many others within the local eco-radical community rolled their eyes. Hundreds of WTO protesters from Eugene were peaceful, they noted, and people from all over the country had joined the black bloc. Of the 570 protesters arrested at the WTO protests, Seattle police identified only four from Eugene.

“I don’t think five or six Eugene hoodies went up there and shut down the city of Seattle,” Shadowalker said. “Media attention after the WTO gave birth to what I call the Anarchy Rock Star, and all these other people got tuned out.”

Those other people were the feeders and the feminists of the movement, the planters of gardens, the militant vegans, the artists and techno-geeks, animal lovers, labor advocates and zine-writers.

They had come together in the late ’90s to oppose the government, corporations and cops — all the institutions they saw destroying free spirits and wild places. And after the WTO protests, they were finally getting international attention for it. “Then it came down to what we wanted to do with that,” eco-radical Chris Calef later reflected by email, “but it turned out we had very little agreement amongst ourselves on the specifics.”

That discord manifested in internal debates about gender roles within the movement, violence versus nonviolence, anarchists versus green hippies and the typical dramas of a cliquish community. “All the while we’re dealing with police informants and infiltrators and state oppression that served to exacerbate the distrust,” Calef added, “and basically just pour gas on the fire.”

From the end of the Warner Creek forest blockade in 1996 to the sentencing of Jeff “Free” Luers in June 2001, Heather Coburn saw eco-radical women doing the work that was most critical to the movement but drew the least media attention: housing, feeding, educating and entertaining the growing masses of activists. “During the heyday of anarchism, even though it was the camo-clad men doing most of the talking, almost all of those projects were being bottom-lined logistically by women,” she said.

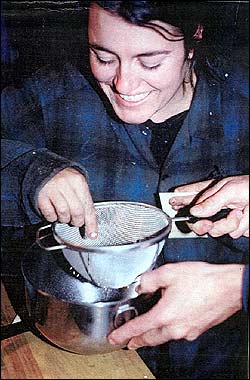

Coburn was among those unsung heroines. In 1998 she and two others took on the lease for Ant Farm, one of several communal pads where hundreds of scrappy activists crashed over the next three years. She ran an all-women’s show called “Vaginal Discharge” on the pirate radio station Radio Free Cascadia and co-organized the “Free Skool” classes that spread activism skills throughout Whiteaker. As a volunteer with Food Not Bombs, she scavenged surplus food from local businesses and served it to hungry people in neighborhood parks. In 1999 she and a friend dug a garden into Scobert Park and launched an urban gardening movement called Food Not Lawns.

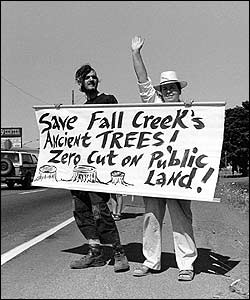

Another caretaker of the movement was Shelley Cater, a friendly single mother then in her 30s who managed Out of the Fog, an organic coffee house by the Amtrak station. Cater invited Fall Creek forest defenders to hold meetings in the café, opened her 5th Ave. home as a campaign headquarters, shuttled donated food and supplies to the aerial village and relieved tree-sitters between rotations. The Fall Creek activists, mostly males under 25, started calling her “Mom.”

A few stalwart women also hung up in the trees — including a woman called Warcry, a smart and fiery activist who’d come to Oregon after sitting in the redwoods of California’s Headwaters Forest. She relished the Fall Creek activists’ fuck-y’all, flag-burning attitude, so different from the peacenik vibe at Headwaters. “In Northern California you couldn’t burn an American flag,” she said with a laugh. “Right up the road in Eugene, it was kind of expected of you.”

But not all Fall Creek women felt safe in the forest. According to an article in Earth First! Journal (“Confronting Oppression, Aug.-Sept. 2001), men were doing most of the cool engineering work — hoisting platforms into the trees, stringing rope bridges between the tree-sits, teaching one another to use the climbing gear — without passing that knowledge onto their female counterparts. Worse, some creepy dudes were allegedly harassing and sexually assaulting women, but male activists weren’t willing to kick out offenders who had valuable skills. “We became pessimistic and depressed with the situation,” wrote the article’s anonymous authors.

In early 2001 the women took a stand and asked four men to leave Fall Creek, two of them for good. During a “gender-bender” month, only women occupied the tree village, teaching each other forest survival skills while men in town organized funds, gathered donations and brought them food — albeit reluctantly. “The men were totally against that,” Cater said.

In Eugene, the gender divide was only getting worse. One woman, who asked not to be identified for fear of retaliation — we’ll call her “S.” — became alarmed around 2000 when an eco-anarchist allegedly commented that he would rape a woman for the revolution. S. launched what she called an anarcho-feminist counter-movement, criticizing and publicly shunning the activists who she felt were fostering abuse — a list that started small, but widened to include even well-known feminists such as Heather Coburn and Kari Johnson. “There was a lack of analysis of white, male, able-bodied, hetero privilege,” S. said. “There’s no way a movement can sustain itself if it’s not built from the bottom up and if all of us haven’t addressed our cultural oppression.”

The anarcho-feminists’ work did prompt some people within the movement to make changes. Most media and activist groups adopted anti-oppression policies, and the question of privilege became one that every activist confronted. But not everyone appreciated it — least of all Tim Lewis, who was perhaps the biggest target of the anti-patriarchy movement. “There was a major attack on men by women who felt like men had too much power in the community,” he said. “Some men left town because they were literally threatened with murder or having their balls cut off.”

The turmoil fueled debates that blazed across a growing number of home-grown independent media forums: on the public-access TV show Cascadia Alive!, which aired weekly from 1996 to 2004; on anarchist philosopher John Zerzan’s show, Radio Anarchy, which began on Radio Free Cascadia and continues today on KWVA; in the pages of Earth First! Journal, which was based in Eugene from 1993 to 2001, as well as in Green Anarchy magazine; and in the films and reports produced by Cascadia Media Collective, which Randy Shadowalker launched in summer 2000.

The media surge stoked more discontent from behind-the-scenes activists who felt that the movement’s largely hard-edged spokespeople didn’t accurately represent them. Shadowalker saw a cliquish, badder-than-thou attitude begin to dominate the eco-anarchist scene, alienating its natural allies on the left — people who sympathized with the movement but lived within the mainstream. “When that [alliance] was gone, the spell was broken,” he said. “It almost went poof.”

Other eco-anarchists saw liberals as unnecessary allies, hopelessly trying to reform a political system whose very existence they opposed. “People were tired of being told what to do or how to act by these PC motherfuckers,” Lewis said.

Compounding the internal strife, federal investigations made Eugene anarchists edgy, paranoid and suspicious of infiltrators. An ongoing string of incendiary crimes in the Pacific Northwest brought the FBI magnifying glass ever-closer to Eugene, directing a hot beam of surveillance onto the scene.

On Dec. 25, 1999, arsonists placed gift-wrapped buckets of fuel rigged with kitchen timers around the Monmouth, Ore. offices of lumber company Boise Cascade, burning the place to ashes. Days later the arsonists explained why in a communiqué sent to ELF spokesman Craig Rosebraugh: “Boise Cascade has been very naughty. After ravaging the forests of the Pacific Northwest, Boise Cascade now looks toward the virgin forests of Chile. Early Christmas morning, elves left coal in Boise Cascade’s stocking.”

Five days after the Boise arson, saboteurs toppled a BPA tower near Bend.

Activists report that police closed in on the scene — tailing them after demonstrations, snooping outside their punk parties, snapping photos of them in the streets. Tim Ream, convinced that the feds were preparing to raid his house, nailed legal statutes pertaining to searches on his front door. “What does it mean to hang out with your lover in your house when you feel like you’re being bugged?” he asked. “It’s a weird space to live in.”

Lacey Phillabaum sat somberly in front of a bed of poppies in Whiteaker, her face darkened by night shadows, and justified the black bloc’s behavior at the Battle of Seattle. “There’s nothing in the world like running with a group of 200 people all wearing black,” she said, blue eyes fixed on a point beyond Tim Lewis’ camera, “and realizing each of you is anonymous, each of you can liberate your desires, each of you can make a difference right there.”

It was mid-June 2000, just days before the premiere of Lewis’ documentary about the combustible trinity: Eugene, anarchy and the WTO — then called Smash!; now titled Breaking the Spell. Anarcho-feminists had been calling Lewis an attention-hogging sexist for months, and now he figured he better get a woman to host his film. Phillabaum, an articulate and bold activist who had been an EF!J editor from 1996-1999, was an obvious choice. She would later regret agreeing to it.

It had been a heavy couple of months. Phillabaum and others, under the banner Eugene Active Existence, had organized the Seven Weeks Revolt!, a roster of community education, street theater and resistance rallies that actually spanned about eight weeks. It kicked off around April 24, when more than 100 people gathered in front of the Lane County Jail to hold a candlelight vigil for jailed Philadephia journalist and convicted cop-killer Mumia Abu-Jamal. Police alleged that protesters blocked traffic, ignored orders to disperse and, in one instance, kicked a burning can at them. Protesters, in turn, accused the cops of showing up in excessive “robo-gear,” intimidating and assaulting them. Police fired rubber bullets at one demonstrator and arrested eight.

Eugene anarchists became the boogeymen of the Northwest, repeatedly blamed for police overreactions at protests. When a group of Eugene radicals joined more than 300 demonstrators in Portland during a May Day march, some 100 cops fired beanbag shots and slammed horses and ATVs into the mass, injuring at least 20 people. Portland’s police chief blamed Eugene anarchists for the excessive police presence, just as cops in Tacoma, Wash., cited rumors of Eugene anarchist mischief when explaining why 350 cops showed up at a canceled steelworkers’ union protest in March.

In the wee hours of June 16, 2000, activists Jeff “Free” Luers and Craig “Critter” Marshall drove from a northwest Eugene warehouse to the Joe Romania Chevrolet dealership on Franklin Boulevard, where they set fire to three pickup trucks in protest of gas-guzzling culture. After they drove away, Springfield police pulled them over for a busted headlight at the request of undercover Eugene police who had been following the pair. That day, Eugene police raided the warehouse where Luers lived and Chris Calef was leaseholder.

The next night, after Lewis’ documentary Smash! premiered on the UO campus, masked activists in black marched toward the Lane County jail to rally for Luers and Marshall. Police again showed up in riot gear, arresting about 40 protesters who linked arms in resistance. Police broke them up with pain holds and pepper spray; one officer allegedly hit a professional videographer in the head with a flashlight.

The following day marked the one-year anniversary of the June 18, 1999 protest, and activists held another protest rally downtown. Police arrested 37 demonstrators, and an officer struck a KLCC reporter with a baton on the head, the blow landing on her headphone band.

In August 2000, the Eugene police released a report absolving themselves of all wrongdoing during the Seven-Weeks Revolt! protests.

A spate of federal laws stiffened the penalties for eco-sabotage during those volatile years. As the FBI’s counter-terrorism budget grew, Joint Terrorism Task Forces increasingly looped local cops into the surveillance of radical environmentalists. A 1999 juvenile justice bill (HR 1501) would have made it a federal crime to share information on bomb-making and created a central database called the “Animal Terrorism and Ecoterrorism Incident Clearinghouse.” Although the bill passed in the House and Senate, it was never enacted as law. In March 2001 the Oregon House passed two bills expanding the definition of organized crime to include sabotage against animal enterprises and the timber industry, punishable by up to 20 years in prison. Warcry noted these developments in an article in the Earth First! Journal (“The Criminalization of Ecology,” Aug.-Sept. 2001).

Still, eco-sabotage burned hotter across the Pacific Northwest. In September 2000 arsonists singed the EPD’s West University Public Safety Station, and four months later the Superior Lumber offices in Glendale, Ore., burned to the ground. On March 30, just as Luers was about to go to trial — “Critter” Marshall had already pleaded guilty and received five and a half years — eco-anarchists attacked Joe Romania Chevrolet a second time, damaging more than 30 SUVs. ELF claimed responsibility in a March 31 communiqué, noting that although Luers and Marshall had been charged with torching the same lot a year earlier, “The techno-industrial state … cannot jail the spirit of those who know another world is possible.”

Less than two months later came the double whammy, the biggest arson the anarchists had seen since the 1998 blaze at the Vail Mountain ski resort. On May 21, 2001 activists burned an office and 13 trucks at Jefferson Poplar Farm in Clatskanie, Ore. On the same day, they torched the office of a biochemist who was doing research on genetically engineered poplar trees at the University of Washington. ELF claimed responsibility in a June 1 communiqué, linking the two arsons and denouncing GE tree research.

On June 11, 2001, Judge Lyle Velure sentenced Luers to 22 years and eight months in Oregon State Penitentiary for arson at the Romania dealership and attempted arson at Tyree Oil Inc. in Whiteaker — a penalty stiffer than that handed to some rapists and murderers. More than a slap on the wrist or even a rap on the knuckles, it was as if Velure had chopped off the hand of Eugene’s eco-anarchist community.

More blows followed in quick succession: In July 2001, Italian military police shot and killed a masked protester at the G8 trade summit in Genoa. Then came the Sept. 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, followed by the free-speech-chilling PATRIOT Act. Eugene anarchists would help light one more arson in mid-October, burning down a hay barn and releasing 200 horses and burros from the BLM Wild Horse Facility in northeast California.

Eugene’s eco-radicals may have been aware of the arsons, and some even impressed, but few say they suspected that the saboteurs were members of their own community. “Half of the arsonists were good friends of mine at one point or another while the actions were going on,” Heather Coburn said, “and I had no idea.”

She still has a hard time accepting that that one of her own housemates was involved in just about all of the sabotage.

It wasn’t just the sabotage crimes and their consequences that squelched eco-anarchy in Eugene. Most involved activists agree that by mid-2001, Eugene’s eco-anarchist scene had imploded on its own.

One exception was the Fall Creek activists, who hung tough in the trees even after an environmentalist lawsuit forced the Forest Service to dramatically reduce the size of the planned logging in order to protect the red tree vole. They hung on until Zip-O-Log Mills finally gave up its plans to log the remaining 24 acres. In 2003 they finally came down from the tree village, having spared 96 acres of forest from chainsaws since “Free” Luers made the first tree-sit in 1998.

Meanwhile, Eugene’s eco-radicals moved on to other endeavors. Some moved away and kept up their activism elsewhere. Some stayed and pushed forward with above-ground environmental projects based out of Eugene. A few ended up in prison; still others moved on to college, families, mortgages, 9-to-5s. And although the movement’s dissipation saddened some activists, it also sparked new endeavors. “For me, the most radical things we did were in the process of falling apart and then getting back together as individuals,” Coburn said.

But four years after the movement deflated, it would return to haunt everyone involved — dragging 10 activists who thought they’d moved on with their lives before federal courts in Eugene. The feds hadn’t closed the books on the eco-anarchists yet.

This is the third piece in a five-part series providing local context for a surge of environmentally motivated sabotage crimes that flared across the West from 1996 to 2001. Since December 2005 the federal government has indicted 18 people for the crimes, mainly arsons, in a sweep known as Operation Backfire. Of those indicted, 12 have now pleaded guilty, four are fugitives and one committed suicide in jail. One has pleaded not guilty and is awaiting trial.

None of those indicted have agreed to speak with EW as they await sentencing, but most were connected to Eugene’s eco-activist scene in its peak years. Except in cases where they have left a record, we minimize their mention here.

In an effort to include more voices in this part of the story, EW has agreed to protect some sources’ identities by using their activist names, or in one case, changing a name altogether.

Finally, we use terms such as “eco-radicals,” “Eugene anarchists” and “anarcho-feminists” loosely throughout this text. While generally referring to the shifting community of people who concentrated in the Whiteaker neighborhood, resisted authority and fought for environmental and social causes, the terms are imprecise. Anarchy by definition is autonomous and unorganized; statements about the community in general do not necessarily apply to every individual associated with it.

Part I: In Defense of Cascadia

https://eugeneweekly.com/2006/11/02/coverstory

Part II: Eco-Anarchy Rising

https://eugeneweekly.com/2006/11/09/news1

Part IV: The Bust

https://eugeneweekly.com/2006/12/07/news1.html

Part V: The Ashes

https://eugeneweekly.com/2006/12/21/news1