Randy Lord and Chris Leebrick rolled into town in 1992, their old Buick Park Avenue packed with the worn clothing and stratospheric expectations of young artists. They were fresh out of college and bubbling with an ambitious plan: to create a first-class theater that features only the best actors, produces timeless plays and keeps ticket prices well within the range of us mortals.

Twenty years later and that plan is still unfolding. With another wildly successful season under its belt and on the brink of opening a new space downtown, Lord Leebrick Theatre Company is celebrating its past accomplishments, while still looking toward the future.

Leebrick and Lord

Like so many great artistic ventures, Lord Leebrick Theatre owes much of its vibrancy to the unabashed, idealistic egoism of the young. “The origin of LLTC was pure selfishness,” says Lord. “A couple of college buddies wanted to advance their growth as artists and make a nice living off that art in the process.”

Local actor Dan Pegoda remembers the buzz around the new boys in town. “These two cats, just a couple of young Turks wanting to put on and be in some cool shows,” recalls Pegoda, who contributes comics to EW. “I remember trying to figure out what Shakespeare character Lord Leebrick was, until I finally got the joke.”

|

|

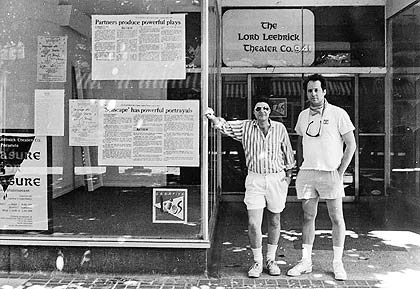

Randy Lord and Christopher Leebrick outside their 901 Willamette location, 1993

|

|

|

Rebecca Nachison & Nancy Hopps in Circle Mirror Transformation

|

With names like Lord and Leebrick, what choice did they have but to use them for a theater? But it was about more than just a healthy love for the family appellation, Lord says.

“Naming the company after ourselves, while many considered this an arrogant and self-centered move,” he explains, “expressed a buck-stops-here mentality. No one had to wonder who was ultimately responsible for the integrity of our productions, who should be the recipient of any glory or criticism. And there was plenty of both to go around.”

Lord’s partner in drama reiterates the scope of their original expectations. “Randy and I had grandiose visions when we were in the initial planning process for the company, and we thought really big things were gonna happen quickly,” says Leebrick. “Then the reality and the hard, hard work set in, and we would look back at those grandiose visions and laugh at our naiveté. It takes time and hard work,” he adds.

Hard work and hard times — such as when Leebrick had his costume stolen before opening night and ended up performing in the dirty old shoes the thief had left in place of the white sneakers he snatched. Leebrick notes that they could “literally fill a book of good stories about the early years.” During the second season, the guys actually started living in the theater.

“Times were tight and we could save money by only paying for one rent,” Leebrick recalls. “I had always wanted to get as close to my art as possible, and that certainly did it. I ended up living at the theater three years to the day — sleeping on a futon, cooking on a hot plate and showering at my gym. Quite bohemian it was.”

The Spectators

Even with actors performing in cast-off shoes and sleeping on the set, audiences at Lord Leebrick shows continued to grow.

“It should be said, we were doing really high quality work up on stage since the beginning,” says Leebrick. “Good acting is what attracted our audience to begin with, and it’s still the most important thing.”

Although both men have moved on to new artistic challenges outside Eugene — Leebrick performs in Portland, Lord teaches in Boise, Idaho — fans here continue to pack the seats. Of all the pieces to Lord Leebrick’s success, the people of Eugene remain key.

“The best thing, really, about LLTC is its audience base,” says director John Schmor, who regularly stages creative Shakespeare adaptations in the space, including last year’s Winter’s Tale. “The range of people who consistently attend, (they’re) curious and responsive and willing to be taken on some strange rides.”

Artistic director Craig Willis notes, “It’s not the same people coming to every show.” According to Willis, every production this year has nearly sold-out, with 98 percent occupancy; that said, each play seems to attract its own peculiar group of patrons.

As an actor, Pegoda sees audiences seated before him as “savvy and smart. And (they) love to be challenged. They sit pretty close to you, and you can feel their attention,” he adds.

The Coolest Theater In Town

Lord Leebrick Theatre consistently manages to attract some of Eugene’s best artists. Willis says that aside from being one of the only paying theater gigs in town, “we have a commitment to excellence and to providing as many resources as we can to support our artists.”

For Schmor, the magic of Lord Leebrick resides in the way the theater company forges connections with other artists. “I like directing smaller casts in an intimate setting,” he says. “I also love the chance to work with community actors — all the different approaches, backgrounds.”

For Pegoda, it’s the plays. “Well, they pick cool shows don’t they?” he says. “That means you end up with thoughtful, scary, philosophical, contemporary, crazy and moving stuff with a good dose of Shakespeare and Chekov and Ibsen and those guys. Cool stuff.”

Sometimes it’s all a little too cool. Anyone who’s attended an opening-night gala senses the complex web of relationships spinning throughout the lobby, and likely ascertains that she might not be an essential part of the clan. Lord Leebrick, with its tight-knit air, can be a hard theater for an actor to break into.

“It’s been generally accepted for many years that only a select few get into their plays,” says a local patron and long-time Eugene theater insider. “They certainly don’t publicize auditions. If one asks, one is told that they’re always posted on the website, but they can be hard to find even there.”

Willis sighs when I ask about the theater’s in-crowd reputation. “We’re exclusive in that I tend to program smaller cast plays,” he explains, noting that this is a decision dictated by the company’s space and budget constraints, as well as being guided by an interest in contemporary plays.

It’s also the difference, Willis says, between being a professional versus a community theater. “The mission of a community theater is to provide as many opportunities to as many skill levels as possible,” he says. “The mission of a professional theater is to provide training for people of all skill levels, and to produce professional plays that meet the expectations that we’ve created in our audience.”

If you want to break onto the Lord’s boards, the theater generally holds two open auditions a year. Much of the season is cast up front, meaning many actors get called back to audition when they’re needed for specific roles. And if you look closely, you’ll rarely see an actor on Lord Leebrick’s stage twice in the same year. And, in just about every play, you’ll see someone new.

Anyone can, and would be well advised to, take an acting class. Lord Leebrick Theatre Company offers lessons in acting, playwriting, voice, movement, youth acting and even summer camps. The training program, which began in 2004, continues to expand.

According to Willis, “Part of the mandate for me is to help strengthen the talent pool. There are actors who manage to accomplish great things without training, but they are the rare exception.”

Willis makes the point that fans expect musicians and athletes to train extensively, so why wouldn’t we expect that actors partake of the same regimen?

Grand Plans For the Future — Broadway!

“Our vision for Lord Leebrick Theatre Company is to become a nationally and internationally recognized theater that makes its home in Eugene, Ore.,” the theater’s website boldly states. No sooner did they pick up the last plastic cups from the June 1 birthday bash than work commenced on the new space.

The company’s capital campaign raised more than one million dollars in 2009 to purchase a building on Broadway, right in the heart of downtown Eugene.

The new theater will seat 125, with the ability to expand to a capacity of 170. Although the larger space will give the company a chance to put on more conventional plays, Willis says Lord Leebrick fare will not differ radically from what fans have come to expect.

In the second phase of the building project, a smaller space will open. “It will be a 99-seat black box similar in size to the Hope Theatre at the UO,” Willis explains. “That space will enable us to program more experimental work and create opportunities for other local artists. We hope to have that space operating by the end of 2013.”

All these seats — and the stages, lighting and sound systems that go with them — require money. “What’s really changed since the Lord and Leebrick days is the amount of corporate and private contributions coming in to the company,” Leebrick says. “I think Craig Willis and company have done a great job of furthering those things along.”

The community has proven more than willing to pitch in thus far, yet more remains to be achieved. For the first phase, which should wrap up in January, theater staff hopes to raise another half-million dollars, and for the final expansion they will need to raise a million more.

Willis says his ultimate goal is to “provide the kind of professional experience our audience expects from the top-tier arts in Eugene.”

The ever-quickening heartbeat of his 1992 project certainly doesn’t throw Lord for a loop. “The fact that LLTC is still around, thriving and expanding, comes as no surprise to me,” he says. “The talent, commitment and community support have always been there. I have no doubt that the next 20 years will prove to be every bit as fruitful and challenging as the first. Long live LLTC,” Lord exclaims.

Leebrick sums it beautifully: “Twenty years later, the LLTC is still rockin’. I love it.”