The UO Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art is trying to capture an era, an art movement, a revolution. When artists use drugs, publications, shelter and lifestyle as tools for expression just as artists preceding them employed cameras, paint and clay; when artworks don’t fit neatly into a gilded frame or beneath a sparkling glass case, museums must adapt and turn the establishment on its head.

Like the glow of a firefly in a jar, the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art (JSMA) will attempt to capture the light and art of the ’60s and ’70s in the American West. Opening Feb. 8, West of Center: Art and the Countercultural Experiment in America will document and recreate the ephemeral art of an explosive 12-year period in this country’s history, 1965 to 1977. Originally curated by the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, the exhibit not only explores the relationship between art and activism but also encourages us to explore the legacy of an artistic era whose effects still reverberate in Eugene, seen in local architecture and happenings like Oregon Country Fair and the Slug Queen pageant. From inflatables to domes, the Cockettes to The Black Panther newspaper, psychedelic light shows to radical feminist lesbian communes, the JSMA is about to become a revolutionary playground.

|

|

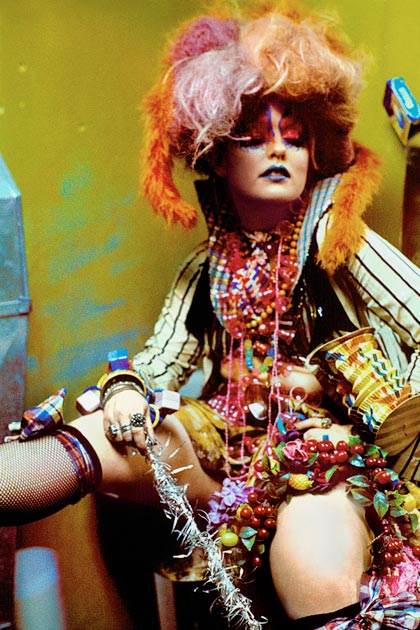

Cockette Fayette Hauser as her ‘cosmic gypsy’ persona

|

|

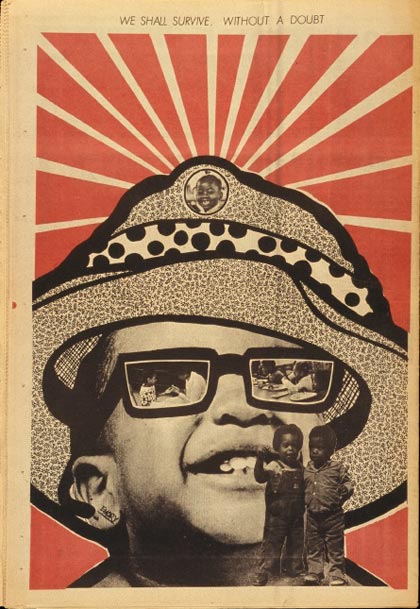

| Print by Black Panther Party Minister of Culture Emory Davis |

|

| A dome under contruction in the artist commune drop city. Photo by Gene Bernofsky |

Genderfuck and the radical theater of the Cockettes

In the late ’60s, performance artist Fayette Hauser went for half a year without uttering a word. “I had a psychic overload with LSD and all these hallucinogenics and I didn’t speak for like six months,” Hauser tells EW.

That was the beginning of Hauser’s time with the Cockettes, a post-gender, “high drag” theater troupe living in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco from the late ’60s to early ’80s. The troupe blurred the distinction between performance and everyday life, wearing their handmade, elaborate glittering costumes and visages not only on the stage for productions like Journey to the Center of Uranus, but also when walking around their neighborhoods or watching movies at home.

“The Merry Pranksters meets The Living Theater was what the Cockettes were,” Hauser says. Like The Living Theatre, the Cockettes tore down the hierarchical structure of traditional theater and created a more communal experience, dissolving the wall between performer and audience.

The troupe also blurred the lines of gender and sexual orientation. “All the Cockettes, if not physically then definitely in their heads, were bisexual. It didn’t matter what your gender was at all,” Hauser says, laughing. Often described as genderfuck — or mocking traditional gender roles — Hauser notes that it was less about gender-flipping and more about expressing your “internal psychic persona.” The glitter-bearded Hibiscus (née George Edgerly Harris III, Jr.), perhaps the most famous Cockette, said in a 1980 interview, “Instead of dressing in drag, I was dressing more as gods. We were all creating mythic figures.”

Hauser sees the bygone era as forward-thinking. “I feel privileged,” she says. “I got to experience and be involved in and contribute to a society that’s like a keyhole peek into a possible positive, brilliantly joyful future.”

Hauser will be giving an artist’s talk 6 pm Tuesday, April 9, and performing 7 pm Wednesday, April 10 (location TBA).

The Black Panther prints of Emory Douglas

On first glance, the bold red and white rays emanating from a smiling boy’s face in “We Shall Survive Without A Doubt” (1969) may lead you to believe the print is a remnant from China’s Cultural Revolution. But on closer inspection, you can see the child is black and wearing thick spectacles that frame images of other black children in school and eating breakfast. These sub-images come from the Liberation Schools and Free Breakfast Program started by the Black Panther Party (BPP) in the late ’60s, programs that were once implemented in Eugene by the local BPP chapter.

The print is one of seven that will be on display at the JSMA by Emory Douglas, the BPP minister of culture and art director for The Black Panther newspaper, where most of his prints were originally published. Douglas acted as minister of culture from 1967 until the early ’80s, a period where he helped transform stereotypical representation of black people in the media as servants, entertainers and athletes, into to a representation of self-empowerment not defined by white standards.

“[Revolutionary] art should be a reflection of the politics and concerns of the community and not something divorced from reality,” Douglas says. “Enlighten a community.”

And the reference to Chinese political posters is intentional. Douglas says that his work drew on “amazing political posters in solidarity with struggles around the world,” including revolutionary art emanating from Cuba, China and Russia.

The Posters of Emory Douglas opens Friday, Feb. 8, at the JSMA.

Ant Farm Bubbles and Buckminster Fuller Domes

“There was a scent of revolution in the air,” Chip Lord says of the year he graduated from Tulane University — 1968. “The anti-war movement, the student movement — nobody in my graduating architecture class wanted to go into the corporate world of architecture … We wanted to change the world.”

That same year, Lord co-founded Ant Farm, a radical architecture, environmental and digital media collective based in San Francisco. Reacting to the rigid Brutalist architecture of the ’50s and ’60s, Ant Farm introduced inflatable “bubble” structures made of plastic and tape that could be blown up with house fans.

“Inflatables were the opposite of that,” Lord says. “They were soft, moveable, lightweight.” And, similar to the DIY culture of today, Ant Farm wanted to democratize architecture and put it in the hands of the people. Lord even produced a free DIY manual in 1971, the Inflatocookbook (the manual can be found online).

“The primary mode of writing was the cookbook,” says Albert Narath, a professor in the UO Department of the History of Art and Architecture. The cookbook was about architects “getting their hands dirty” and reengaging with building and society, Narath says. The JSMA used that cookbook, with help from School of Architecture and Allied Arts (AAA) students, to create their own inflatable within the museum’s walls. The JSMA is also hosting “Eugene’s First Incredible Inflato-Contest,” a city-wide inflatable competition whose top four finalists will “bring their inflatable to life” downtown during the March First Friday ArtWalk (visit jsma.uoregon.edu/inflatocontest for entry guidelines).

AAA Students have also constructed a partial 15-foot-high dome in the museum, drawing on the iconic geodesic dome architecture of Buckminster Fuller that influenced living-art communes like Drop City in Colorado. Video of Drop City will be projected on the JSMA dome.

“I think it’s so instructive for students to become involved and actually building the mock ups in the exhibition,” Narath says. This practice has a long legacy at the UO. Narath explained this legacy to students in a lecture he gave the night before the dome construction, pointing to images of Buckminster Fuller building geodesic domes with UO architecture students when he visited campus in 1953 and 1959. This generation of students was among the first to prioritize the importance of sustainability and the environment in architecture. Narath points out that it’s today’s students “who are having their turn at figuring out what it means to be an architect in a world that faces many of the same problems.”

Chip Lord will be giving an artist’s talk at 6 pm April 18 (location TBA).

What a long strange trip it’s been

“One of the goals is to really tap into the history of Eugene, the ’60s and ’70s legacy,” says Jessi Ditillio, the curator for West of Center at the JSMA. Ditillio says the JSMA exhibit is unique because it will broadcast video interviews of Eugeneans who lived through the era on flat screens around the museum. West of Center will also explore ephemera from the Womyn’s Lands of Southern Oregon, the light shows of The Single Wing Turquoise Bird and the experimental choreography of Anna Halprin. “This show is an experiment in how to alter the experience of the museum and art history,” Ditillio says.

And although this will be an interactive exhibit, Ditillio asks that museum-goers please get high before the show.

West of Center: Art and the Countercultural Experiment in America opening reception 6 pm Friday, Feb. 8, at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art. For full exhibit listings and further information, visit jsma.uoregon.edu/westofcenter