Before service members leave for Afghanistan, military regulations demand that they prepare for the unpleasant possibility that they may never come home. The Navy requires that you meet with a military lawyer to fill out a will, designate an executor and assign your survivors benefits. It can seem overdramatic when you are being called back from civilian life, and jokes about who should get a favorite baseball glove or why leaving a car to a sibling would be a disaster help cut the tension.

But when you sit down to an empty page to write your last letter home — the letter to be delivered if you are killed — there is no one to whom jokes can be made to lighten the moment. As you look over the words, you are forced to imagine the next set of eyes that might read them.

It is important to consider carefully who should hold onto the letter that you hope is never read.

Giving it directly to my wife, Katie, an Air Force JAG (judge advocate general), is not an option. On my last deployment I left her some letters for the birthdays, anniversaries and holidays I would be missing. She unfailingly opened them monthslong before the occasions they were meant to mark. I suppose that indicates I should write more letters. Even without that tendency, it would be cruel to have such a letter sitting ominously on a shelf at home.

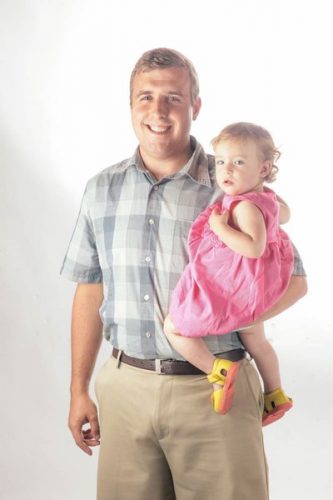

So I turned to Jesse, a fellow sailor, father of two girls and the friend who warned me that being sent overseas after the birth of my daughter would be infinitely more difficult than past deployments overseas. I ignored his warnings to leave the Navy Reserves, which would have made me ineligible for this mobilization, during our years together in law school.

But leaving the Navy would have gone against the reasoning that compelled me to join in the first place, straight after graduating from South Eugene High School in 1998, reasoning most recently captured in a demand for global responsibility eloquently expressed at the United Nations by Malala Yousafzai, a 16-year-old Pakistani girl shot in the head by the Taliban.

But as I looked at my newborn daughter Madeleine in her mother’s arms, five days after the Navy confirmed the involuntary mobilization orders, I concluded that Jesse had been far wiser than I understood.

Unfortunately, once orders are issued, they are rarely reconsidered. The 1 percent of Americans being cycled and recycled through our decade of war in Asia gets little reprieve from the honor of serving. The nation regularly recalls those who have left active duty to fight in conflicts they thought they had left behind. After more than a decade of war, the ability to transition from serving in uniform to reintegrating as a veteran in American society — as the Greatest Generation did following World War II — has become more difficult.

Perhaps that’s a good thing for a military that has become more remote from American society. As former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mike Mullen said in 2011, “Our work is appreciated, of that I am certain. But I fear [civilians] do not know us. I fear they do not comprehend the full weight of the burden we carry or the price we pay when we return from battle.”

Such an understanding is vital, Mullen said, “because a people uninformed about what they are asking the military to endure is a people inevitably unable to fully grasp the scope of the responsibilities our Constitution levies upon them.”

The hidden draft that has filled in the gaps of an active duty force stretched thin over the last decade also maintains a stronger connection between the civilian population and the “volunteer military” fighting the war in Afghanistan. Of the 2.4 million Americans who have served in Iraq or Afghanistan, approximately 30 percent have been reservists or National Guard members.

Certainly in my case mobilization reminded law school classmates that the war could reach even into their ranks to pull away someone they knew.

Such esoteric thoughts were little comfort in my final days with Katie and Madeleine. Instead, we found solace in a visit to the San Diego Zoo (which offers service members complimentary entry) and in the generosity of the Rock ’n Fish restaurant manager who covered our last dinner together. Serious conversations about the challenges of modern military service across the military-civilian divide seem rare. When such conversations occur, they easily fall into the traps of adoration or pity. Lacking a common vocabulary, simple gestures of support can make a tremendous difference.

In the end, the most difficult moments of military service demand the assistance of those who have worn a uniform. So as I return to Kabul to assist in the end of the direct American involvement in Afghanistan, Jesse will keep my last letter home, the fifth I have had to write. I look forward to retrieving the letter next June, burning it unopened.

Jake Klonoski is from Eugene and has been a U.S. Navy submarine officer since 2002, serving in Italy, Bahrain, Japan, Kosovo, Afghanistan and plenty of time at sea. He left active duty in 2010 and was mobilized after graduating Stanford Law School in June 2013 for service in Kabul assisting in economic development and stability operations.