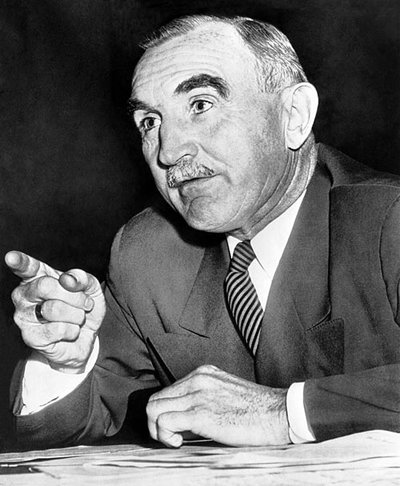

The Tiger of the Senate. The Conscience of the Senate. Mr. Education. Maverick. The principled stances of the late Oregon Senator Wayne Lyman Morse earned him these nicknames and more. Morse’s uncompromising positions on the Vietnam War, civil rights, free speech, the powers of Congress and putting people before corporations also earned the beetle-browed orator the undying respect of some and the ire of others.

Quintessential Oregon author Ken Kesey once said of Morse, “When he looked at you, you felt pinned against the wall, like a bug with a pin in it.”

Morse is also known for his battle cry: principles before politics. His grandson, Father Peter Eaton, dean of St. John’s Cathedral in Denver, Colo., says that Morse was among a generation of politicians who were committed to principles — different from the elected officials who we are seeing now, driven by elections and political concerns.

Morse’s name itself has been used as a battle cry lately. The senator, whose time in office lasted from 1944 to 1968, was one of only two votes against the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution that led to the expansion of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. He argued fervently that the citizens should be making foreign policy decisions and have a voice in government.

A constitutional scholar, talented speaker and take-no-prisoners critic, part of Morse’s legacy is Lane County’s Wayne Morse Terrace and Free Speech Plaza. And that legacy, according to critics of a recent 4-1 County Commission vote to close the plaza from 11 pm to 6 am every day, is sullied when free speech is given a curfew.

Morse against the war

Recent threats of an American intervention in the civil war in Syria, after chemical weapons were used against civilians, brings up the specter of past uses of military force — in Iraq based on false information on weapons of mass destruction and also in Vietnam. This coming year marks the 50-year anniversary of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution.

Wayne Morse was firmly against a war in Vietnam, and the Free Speech Plaza has hosted anti-war protests for decades.

Politico Scott Bartlett says when he came to Eugene for school he was mildly pro-war, but became an anti-war protester after encountering Morse’s thundering speeches at anti-war rallies at the EMU (also home to a “free speech plaza”) on the University of Oregon campus in the 1960s. Barlett went on to become a campaign aide and adviser to Morse in the early 1970s and to later work for the Clinton administration.

Morse didn’t just oppose the war, he wanted the American people to have a say in foreign policy. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution arose in 1964 after an alleged attack on a U.S. ship patrolling in the gulf. Morse was one of only two votes against the resolution, which he opposed not only because it drew the U.S. deeper into an open-ended military conflict but also because, according to Morse, who was an attorney and former dean of the UO law school, it violated Article I of the Constitution by letting Congress surrender its authority to check the president’s power.

Morse, in one of his fiery denunciations, told a reporter, “No war has been declared in Southeast Asia, and until a war is declared, it is unconstitutional to send American boys to their death in South Vietnam, or anywhere else in Southeast Asia. I don’t know why we think, just because we’re mighty, that we have the right to try to substitute might for right.”

The reports of the Gulf of Tonkin incident were later found to have been inaccurate and misleading, but Morse’s anti-war stance was nevertheless unpopular, as was his endorsement of Republican Mark Hatfield for Congress over fellow Democrat Robert Duncan, based on Duncan’s hawkish stance on the war. Morse at the time was a Democrat, but over the course of his political career was “tri-partisan,” jokes Margaret Hallock of the UO’s Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics. Morse was elected to the Senate as a Republican, became an independent when Eisenhower selected Richard Nixon as his running mate and then later became a Democrat, which allied more strongly with his progressive ideals.

Hallock never met Morse, but as a labor economist and a founding member and director of the Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics, she is an enthusiastic steward of his legacy. Morse could be strident, she says, and self-righteous, but that went hand-in-hand with being an iconoclast, independent and unafraid to speak his mind.

Janet Mueller, who worked for Morse in Washington, D.C., says the senator’s “arguments against American involvement in Vietnam could easily be applied to the various international conflicts the U.S. has been engaged in more recently.”

She says from his early days as a labor arbitrator — which earned him yet another nickname, “the Boss of the Waterfront” — to his Senate career, Morse “was never afraid to speak his mind and challenge policies, which he felt were not in the public interest or in accordance with constitutional or legal principles.”

Morse might have hated the war, but he didn’t let that affect how his office handled casework for members of the military from Oregon, says Mueller, who was a military caseworker and later a secretary/aide under Morse. “Military and draft problems were addressed thoroughly and expeditiously on the merits of each case, not on what the senator might have recently said or how he might have voted on Vietnam.”

Eaton points out that these issues are still before us, and Syria is a good example of “the fact that we are still trying to figure out how the president and the Congress act together with respect to the business of making war.”

The price of free speech

Wayne Morse knew that free speech is not always popular speech, says Lauren Regan of the Civil Liberties Defense Center (CLDC). And Morse “paid with his political career to save lives,” Bartlett adds.

Morse lost the 1968 election to Robert Packwood, partly due to Morse’s unpopular stance against the war in Vietnam, but also because his speechmaking skills didn’t translate well to the two-minute soundbites the televised debate against Packwood called for. Packwood, who later left office after a sex scandal, criticized Morse for not doing enough for the people of Oregon — pointing to his ban on exporting raw logs off federal lands and the amount of money citizens got back in taxes.

Morse died in 1974 at the age of 73, while campaigning to get his Senate seat back, and the UO’s Wayne Morse Chair was founded that same year. Tributes to Morse abound. The Wayne L. Morse Federal Courthouse, the Wayne Morse Commons at the UO law school, the Wayne Morse Youth Program and its Wayne Morse Now award and the Wayne Morse Family Farm and dog park. And then of course there is the Free Speech Plaza with its podium for public speaking and a statue of Morse at his oratorical best, pointing an impassioned finger at some long-gone foe.

According to a 2005 press release from Lane County, the “Wayne Morse Free Speech Plaza was envisioned by the Wayne Morse Historical Park Corporation and first approved by the Lane County Board in 1984 to ‘better enable Lane County’s citizens to exercise their precious rights of free speech and assembly.’”

In 1990 the County Commission specified in its Administrative Procedures Manual (APM) that the “actual free speech area” was a specific area on the Wayne Morse Terrace in response to a two-week homeless protest, according to county documents. That area was later designated to be 71 by 73 feet. The APM is subordinate to the Lane Code and the Lane Manual when it comes to running the county.

In 2005 the plaza was upgraded with plaques, paving stones and the bronze statue of Morse made by Mexican sculptor Gabriel Ponzanelli. For some time the Morse Youth Program used the plaza on Saturdays from April until Oct. 20 — a day that the city has historically declared Wayne Morse Day — until 2006 when G.V. Stathakis, chair of the Morse Youth Program, says the Lane County Commission cut off electricity to the plaza. The Morse Youth Program still gives out its Morse Now award, with Lauren Regan winning in 2012.

Commissioner Pete Sorenson, who met Morse while he was working on Congressman Jim Weaver’s campaign, says Morse should also be remembered for his civil rights work — he voted against the 1957 Civil Rights Act because he felt it didn’t go far enough — as well as for his fight for education funding and support of union labor. He calls the curfew on the Wayne Morse Free Speech Plaza “a travesty” of Morse’s legacy.

Sorenson voted against the recent Lane County “emergency” closure of the Free Speech Plaza as well as against the move to close the plaza from 11 pm until 6 am. In August, a Eugene Municipal Court judge ruled in favor of protesters from SLEEPS (Safe Legally Entitled Emergency Places to Sleep), who said their constitutional rights were violated when the county closed the plaza citing health issues based on the alleged presence of feces. Regan and the CLDC represented the homeless protesters.

Stathakis says on this, the 40th anniversary of Morse’s passing, there is no doubt that he would be doing everything in his power to help the homeless. “I knew him well; I bet he would call them ‘citizens without addresses.’”

The closure of the plaza directly affected the homeless protesters, but David Fidanque of the American Civil Liberties Union says the issue is broader than that. He says the ACLU believes that the protection of freedom of assembly and redress of grievances under the Oregon Bill of Rights prohibits any rule or law that prohibits assembly based on time of day.

Morse “strongly believed in the right of Oregonians to petition their elected representatives without reprisal,” Mueller says.

And one of the historic places that the American people have gone to get their voices heard by the public, by the media and by their elected officials, without reprisal, has been the steps, sidewalks and plazas in front of county courthouses and government buildings. That’s where they would actually stand on their soapboxes.

Fidanque says while you can put reasonable measures in place, you can’t simply prevent people from assembling in these traditional areas of free speech. If there are harms — safety or health issues — then you address the harms, you don’t prohibit assembly.

He points to events in the U.S. and around the world of spontaneous public gatherings that have changed history from the people of Moscow in the days of the Soviet Union preventing troops from arresting Parliament to residents of Cairo gathering in Tahrir Square.

Designated “actual free speech area” or not, Fidanque says the attorneys of the Oregon ALCU, who have been working on an ongoing case involving a 24-7 vigil at the state capitol, argue that under the Oregon Constitution there is a an independent right to gather and redress grievances.

According to Chair Sid Leiken, Fidanque’s comments to the County Commission on the issue were referred to county counsel for follow up.

Regan says, “The framers of our Constitution believed that it was a cornerstone of the new democracy — the right of citizens to assemble, redress grievances and petition government without repercussion. There was never a time frame in which that would occur. No alarm clock at 11 pm.”

In addition, in her SLEEPS case Regan argued that when the government designates an area for free speech it becomes a traditional public forum where the right of the government to limit expressive activity, such as protests, is sharply restricted.

“What’s the big deal? Who’s going to be there before 6 am?” Regan asks. “If the First Amendment is bent and eroded in this circumstance, where will the line be drawn?”

Republican Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona once asked Morse on the floor of the Senate, “What does it take to please the senior senator from Oregon?”

Morse told journalist Mike Wallace in a 1957 interview that his answer was “Just clean government. Just clean government, and I’m going to continue to raise this voice for clean government whether there’s a Democrat or a Republican in power.”

Just clean government and the First Amendment right to peaceful assembly, to petition for a governmental redress of grievances and free speech without a curfew.

The Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics presents Shannon Minter, legal director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights, on “Marriage and More: The future of the LGBT rights movement,” 7 pm Oct. 3, 175 Knight Law Center, UO campus. For more on Morse Center programs and speakers go to waynemorsecenter.uoregon.edu