Spiritual fracture and cultural alienation are at the heart of Ecstasy: A Water Fable, a play by Egyptian-American writer Denmo Ibrahim based on the Sufi tale “When the Waters Were Changed.” Directed by Michael Malek Najjar, UO’s University Theatre’s production of Ibrahim’s work — a triptych that flashes among three characters all seeking some form of reconnection with their origins — is technically adept and swift, clocking in at about 90 minutes. It is pretty to look at, and the traditional music, played live on several Arabic instruments (such as the zurna, ney and djembe) by local band Americanistan is hypnotic and, at times, haunting.

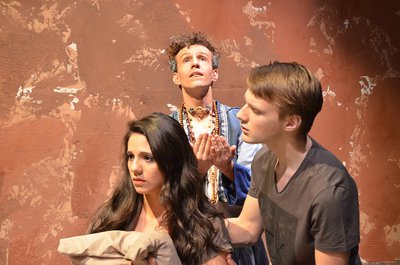

And yet, despite Ecstasy’s formal excellence (or perhaps because of it) the play, for me, was oddly inert. I engaged with the stories — of Pipeman (Alex Mentzel) in his frantic search for God, of the Picture Lady (the excellent Kiara Bernhart) and her dislocation from past and family, of the Westernized Mona (Jessica Ray, also excellent), a stranger in a strange land — but they left me mostly unmoved. The production lacked some essential passion, as though too much respect had been paid to its supposedly exotic nature, leeching it of blood. At times, it seemed a museum piece, a diorama of whirling dervishes.

Of course, this could just be me. As a proud Protestant with a deep aversion to transcendental tourism, I’m naturally suspicious whenever Eastern mysticism gets transplanted to our native soil. It’s not that I’m opposed to seeking communion with the Universal Spirit or Divine Source, as practiced in Sufism; it’s more to the point that Western presentations of foreign concepts and stories often succumb to a dynamic of exotic anxiety, where sacred things are treated with such overweening respect that they are robbed of their vitality. At times, Ecstasy felt more anthropological than dramatic, like a primer.

Much of the problem of Ecstasy, I believe, lays in this tension between fidelity to the Sufi tale and translation of its unfamiliar concepts into the universal language of the stage. As playwright, Ibrahim gives the audience a point of access by roughing up and modernizing some of her characters, as when the Picture Lady hilariously spouts obscenities during her monologue. Such moments work well to de-romanticize what’s going on, to make it breathe with real life, but it’s not enough. The elements of Sufism, such as the cultural importance of water, remain abstruse and confusing, hence the elaborate notes explaining the meaning of the play in the program.

None of which is to say this production is a failure. Taken moment by moment, Ecstasy is full of beautiful movement and song, and it offers intriguing glimpses, as it flashes among its three central stories, into the source of our human desire for (re)connection with each other and the universe at large. The play is richly suggestive, even if the individual scenes don’t always resolve into a coherent story. In a sense, Ecstasy falls victim to the very fragmentation it depicts. But even artistic fragmentation needs a kind of unity to give it voice, and this production remains less than the sum of its parts, fascinating as they are.

Ecstasy: A Water Fable runs through March 16; free for up students, $12 students and seniors, $14 general